Dynamics

|

Generational Dynamics |

| Forecasting America's Destiny ... and the World's | |

| HOME WEB LOG COUNTRY WIKI COMMENT FORUM DOWNLOADS ABOUT | |

|

These pages contain the complete manuscript of the new book

Generational Dynamics: Forecasting America's Destiny,

written by John J. Xenakis.

This text is fully copyrighted. You may copy or print out this

material for your own use, but not for distribution to others.

Comments are invited. Send them to mailto:comments@generationaldynamics.com. |

O thus be it e'er, when free men shall stand Between their loved homes and the war's desolation; Blest with vict'ry and peace, may the heav'n rescued land Praise the Power that hath made and preserved us a nation! Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just, And this be our mot-to, "In God is our trust!" And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave. -- Stanza 4, The Star Spangled Banner, Francis Scott Key, 1814

If you're an average American, you know almost nothing about American history, and may not even know the difference between the Civil War and the Vietnam War. In fact, that's why there are generational cycles in history: most people have almost no knowledge of events that occurred before they were born, and so repeat mistakes of an earlier generation.

On the other hand, it you're reading this book, then you probably know more about history than the average.

This chapter is written to provide new information to you, no matter which of those two categories you're in.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The chapter reviews and analyzes American history using the generational (80-year cycle) methodology. This methodology provides a way to gain a new overview of American history, if this is your first exposure, and it provides additional insights and perspectives if you're already a student of history.

A book on history will almost always center on the nation of the author, and this book is not a major exception. But if you really want to understand the workings of history, you have no choice but to expand your scope of interest, and sometimes move the center of the universe away from your own nation to some other nation -- at least temporarily.

Here's the basic arithmetic: In the 15,000 or so years of recorded

history, there have been thousands, or tens of thousands, of

individual tribes or societies formed by primitive men and women

moving from place. Today, there are about 250 nations, comprising

about 9 major civilizations (Western, Latin American, African,

Islamic, Sinic, Hindu, Orthodox, Buddhist, Japanese.

(Western, Latin American, African,

Islamic, Sinic, Hindu, Orthodox, Buddhist, Japanese.

Now here's one more indisputable fact: In that same 15,000 years, the amount of land available on earth has remained relatively unchanged, despite the fact that these tribes and societies all had a tendency to grow and become more populated.

How did we go from tens of thousands of tribes to such a small number of nations and civilizations, living on earth with a constant amount of land? Sometimes tribes would combine via a friendly merger, but the answer, in almost all cases, is through war. Two tribes grow larger and larger, they bump into each other trying to occupy the same farmland or hunting lands; they may try to coexist for a while, but eventually they settle it with a war. The victors keep the land in dispute, and not infrequently murder all the men in the defeated tribe and rape all the women, unless some more agreeable settlement can be reached first.

Most history books treat these wars as somewhat random events that occur from time to time in different places.

Our approach is quite different, since we're analyzing history from the point of view of generational cycles. We see two tribes or societies compromising with each other, or at worst having only small wars, as long as possible, as long as most decision makers still remember how awful the last big war was; when the new generation comes in, then there's another big war.

So let's start with American history, and let's look at it in a new way. The major wars were not random events, but were great periodic events, influenced by events that were remote in both time and place.

As you study this, don't just think of yourself as an American. Think of yourself as an American sometimes, but at other times an Indian, a Brit, a Northerner, a Southerner, a Japanese, or a German. Try to understand the point of view of each of these people, and ask yourself what motivated them to go to war.

The most devastating war in American history was the Civil War, but the most devastating war in New England's history occurred about 100 years before independence between the colonists and the local Indian tribes. This war cast a shadow that lasted until the American Revolution, and had an enormous influence on events leading all the way up to the Revolution.

The standard America-centric view of this war is as follows: The colonists and the Indians got along pretty well until the colonists started taking too much valuable farming and hunting land. There was a devastating war in the years 1675-76, just one of many wars that the colonists, and later the "white man," used to steal land from the Indians.

That's an interesting political point of view, and it's true in a sense, but it doesn't provide any real understanding unless we expand the scope of our vision a little bit.

|

In the year 1600, throughout what is now the United States, there

were some 2 million Indians within 600 tribes speaking 500

languages . What happened, starting at that time, was a "clash

of civilizations" between European culture of the colonists and the

indigenous culture of the Indians. These cultures were so different

that haven't yet merged even today, inasmuch as many Indian tribes

still live separately on reservations. It's ironic that the American

"melting pot" has merged so many cultures, but has not yet entirely

merged the preexisting Native American cultures.

. What happened, starting at that time, was a "clash

of civilizations" between European culture of the colonists and the

indigenous culture of the Indians. These cultures were so different

that haven't yet merged even today, inasmuch as many Indian tribes

still live separately on reservations. It's ironic that the American

"melting pot" has merged so many cultures, but has not yet entirely

merged the preexisting Native American cultures.

Most history books treat "the Indians" as a monolithic group, as if they spoke with a common voice and common intent, but that's far from the truth. There were undoubtedly many brutal wars among the 600 tribes of the time. What would have happened if no colonists and no other outsiders had come and intervened in the life of the Indians? What would have happened? There's no way to know, of course, but it's likely that one or two of the tribes would have become dominant, wiping out all the other tribes in numerous wars. That's the nature of human societies: As they grow larger and run into each other, they go to war, and the dominant societies survive.

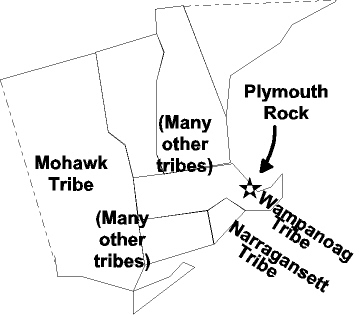

For the purposes of our story, we're going to focus on just three of those Indian tribes: The Wampanoag tribe that occupied what is now southeastern Massachusetts (where Plymouth Rock is) and the Narragansett tribe that occupied what is now Rhode Island, and the Mohawk tribe (part of the Iroquois) of upstate New York.

There is some historical evidence that a major war among these tribes

had occurred in the years preceding the colonists' arrival at

Plymouth Rock, probably in the 1590s. The Wampanoag and the

Narragansett tribes were particularly devastated and weakened by that

conflict.

at

Plymouth Rock, probably in the 1590s. The Wampanoag and the

Narragansett tribes were particularly devastated and weakened by that

conflict.

| The victors keep the land, murder the men, and rape the women |

So, when the pilgrims arrived at Plymouth Rock in 1620, in the midst

of the Wampanoag tribe, they had little trouble developing a pleasant

cooperative relationship. The Wampanoag Indians were in an awakening

period, and they taught the colonists how to hunt and fish , and

in autumn of 1621, they all shared a Thanksgiving meal of turkey and

venison.

, and

in autumn of 1621, they all shared a Thanksgiving meal of turkey and

venison.

Most significant was the colonists' early "declaration of independence." Before the colonists landed in 1620, they signed the Mayflower Compact, where they agreed that they would be governed by the will of the majority. This laid the framework for the view that neither the king nor parliament had any say in colonial government. And why would they need the King anyway? After all, they could provide for themselves, and they were friendly with the Indians.

This friendliness extended to trade. Before long, there was a mutually beneficial financial arrangement between the Indians and the colonists. The colonists acted as intermediaries through whom the Indians developed a thriving business selling furs and pelts to the English and European markets, and they used the considerable money they earned to purchase imported manufactured goods.

|

There were two particular Indian chiefs who are important to this story: one is a father and the other is his son, who took over when the father died in 1660.

The father's name is Massasoit, chief of the Wampanoag Indians, the Indian tribe most familiar to the Massachusetts colonists.

We have no way of knowing Massasoit's history. He was born around 1580, and so he must have been alive during the devastating war with the Narragansett. In fact, since he became Chief, he may well have been a hero who fought in the war in his teen years. With his personal memory of the devastating results of the last all-out war, he would not want to go through another war again unless absolutely necessary.

We have no way of knowing the details of what the Indian tribes had fought over, but chances are it was over what most wars are fought over -- land. Each tribe wanted the best hunting, fishing and farmland for its own use. But Massasoit maintained friendly relationships with the colonists because of the financial benefits, and because he was a wise, elder leader who didn't want another big war in his lifetime.

Several dramatic changes occurred in the 1660s, when Massasoit died.

"The relationship between English and Native American had grown

inordinately more complex over forty years ," according to

Schultz and Tougias. "Many of the important personal ties forged

among men like Massasoit and Stephen Hopkins, Edward Winslow, and

William Bradford had vanished. The old guard was changing on both

sides, and with it a sense of history and mutual struggle that had

helped to keep the peace."

," according to

Schultz and Tougias. "Many of the important personal ties forged

among men like Massasoit and Stephen Hopkins, Edward Winslow, and

William Bradford had vanished. The old guard was changing on both

sides, and with it a sense of history and mutual struggle that had

helped to keep the peace."

Massasoit was replaced as Chief by his oldest son, Wamsutta -- who died under mysterious circumstances that were blamed on the colonists. The younger brother, Metacomet, nicknamed King Philip by the colonists, became Chief.

Things really began to turn sour in the 1660s for another reason: Styles and fashions changed in England and in Europe. Suddenly, furs and pelts went out of style, and the major source of revenue for the Indians almost disappeared. This resulted in a financial crisis for the Indians, and for the colonists as well, since they were the intermediaries in sales to the Indians.

But that's not all. Roughly 60-70 years had passed since the end of the last tribal war. The Mohawk War (1663-80) began, and created pressure from the west. The colonists were establishing ever-larger colonies in the east. In this pressure cooker atmosphere, the Wampanoag tribe, led by a young chief anxious to prove himself, allied with their former enemy, the Narragansett tribe, to fight their new enemy, the colonists.

One of the most fascinating aspects of history is how two enemies can carry on a brutal and almost genocidal war, and then, 80 years later, can be allies against a common enemy. This appears to be the way things are going today with our old World War II enemies, Germany and Japan, and it's certainly true of protagonists in the most destructive war in American history, the Union and the Confederacy in the Civil War.

| Massasoit must have fought in a major war with another tribe in the 1590s |

In this climate of general war tensions and financial distress, we see the same pattern for how a major war occurs: There's a generational change, then a period of financial crisis, then a series of provocative acts by both sides, each of which is a shock and surprise to the other side, and calls for retribution and retaliation.

It's important to understand the role of all three of these elements. In particular, without the generational change, the provocative acts are met with compromise and containment, rather than retribution and retaliation.

This is particularly important in understanding what's going on when one side is provocative and the other side is compromising. This often means that the generational change has occurred on the first side, but not yet on the second.

In our own time, the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center was a provocative act by Islamist extremists, but was met by no more than a criminal trial for the perpetrators; the 9/11/01 attack was met with a war against Afghanistan.

The actions of the colonists, in the face of provocations by the Indians, seemed to display a similar range of goals. In the 1660s, perpetrators were brought to trial, and executed if found guilty of the most serious crimes.

The trial process was brought to a head in 1671, when King Philip himself was tried for a series of Indian hostilities, and required by the court to surrender all of his arms; he complied by surrendering only a portion of them.

After that, the trial process seems to have fallen apart, as the colonists began to lose their patience and willingness to compromise. Trials were still held, but they became mere provocations: they were kangaroo courts with the results preordained, and the Indian defendants were always guilty.

These provocations kept escalating, until King Philip's War began with Philip's attack on the colonists on Cape Cod.

The war was extremely savage and engulfed the Indians and the colonists from Rhode Island to Maine. There were atrocities on both sides, and the war ended with King Philip's head displayed on stick. His wife and child were sold into slavery.

This was the most devastating war in American history on a percentage basis, with 800 of the 52,000 colonists killed. (It was devastating for the Indians as well.)

| This was devastating: 800 of 52,000 colonists killed |

If you want to start understanding how one world event sequences to the next, you have to start examining each event in the light of its position within the 80-year cycle.

Let's take a lighter example, the Salem Witch trials of 1692. Overall, 150 witchcraft subjects were jailed, the result of a frenzy that grips the town after a group of young girls feign hysteria and accuse a family slave of bewitching them.

If you forget about the previous major war, you would think that the only explanation is that someone had poisoned the water. But in fact, Salem was located in the heart of the battlefields of King Philip's War, which had ended only 14 years earlier. It's likely that in 1692 there were few males above age 30. In those austere, heavily religion-conscious times, the concerns about witches represented the same overreactions to anxieties that Communist blacklists represent following World War II.

The Salem Witch trials provide a weird but relevant example that helps us understand what life must have been life following King Philip's War -- and any crisis war. Those who lived through it are always into setting rules. The ones who survive always feel guilty and angry. Why didn't I protect my family better? Why didn't we live somewhere else where we would have been safer? Why wasn't I a more religious man, so that God wouldn't have punished me (and us) this way? Why weren't English soldiers here to defend us?

That brings us back to the Mayflower Compact, signed in 1620, which guaranteed that local government would be independent of the English Crown. The colonists had thought they would build their new community without outside interference, with their own rules and their own self-government.

After the war, they felt forced to acquiesce completely to English rule. All home rule was dissolved and Governors would be appointed from London. British troops would protect the colonists from the Indians and the French, and colonists would pay taxes to the Crown in return.

Isn't that eerie? Those were all the things that caused trouble later, and led to the Revolution.

And that's how one crisis war leads to another. When one war ends, outsiders often impose compromises to prevent the war from repeating. Those compromises only last so long, and often end up being the root causes of the next war.

After every crisis war, there's always a generation gap that causes social turmoil about halfway to the time of the next crisis war. The turmoil is caused by rebellion against authority -- those too young to remember the war rebel against the austere rules imposed by those who lived through the war.

Many people believe that the social turmoil of the 1960s and 70s, with the antiwar movement, the environmental movement, the women's lib movement, and so forth, was unique in American history. But nothing could be further from the truth.

The social turmoil that occurred in the 1730s and 40s was so great, history has given it a name, "The Great Awakening in American history."

For our study of the cycles of history, the actual details of both the wars and the awakenings are not as important as the simple fact that they occurred. Nonetheless, we look at a few of the details in order to gain insight into how the cycles of history work.

The great compromise of the crisis of the late 1600s was that the colonists were forced to cede political control to the English Crown, since the colonists needed the protection of the British army from the French and the Indians. This was a serious issue, since England was at war with France and Spain throughout many years of mid 1700s, and North American often became a battlefield.

Closely related to political control was religious control. The official religion in England was, well, the Church of England, which was supported by and closely tied to the English government. It was called the Anglican Church in the colonies.

The Anglican Church never did have much success in establishing religious control in the colonies, as congregations of Puritans, Presbyterians, Congregationalists, Baptists, Quakers and many other religions sprang up in the colonies from the beginning, and had to compete with one another for followers.

Starting in the 1730s, something brand new came about -- something we recognize today in the form of "televangelists." Various preachers went from city to city, telling thousands of rapt listeners that they would be punished for their sinfulness, but could be saved by the mercy of an all-powerful God. To take one example, John Wesley, born in 1703, created the Methodist religion, and traveled on horseback throughout the country for years, stopping along the way to preach three or four sermons each day.

| The Great Compromise was that the colonists accepted political control by the Crown |

As we go from crisis war to crisis war, we'll see that there's always an "awakening" midway between two crisis wars. This happens because a crisis war creates a "generation gap" between people who lived during the war and the kids who were born afterwards.

The traumatized older generation tries to impose controls on the kids, so that "nothing like that will ever happen again." The kids, who have no personal knowledge of the war's horrors, rebel against the controls.

The Great Awakening of the 1730s and 1740s was not just a religious revival; it was also an act of rebellion against the older generation that favored control by the British in return for protection. By rejecting the Anglican Church, the colonists were symbolically rejecting British control.

All the contradictions and compromises that were forced upon the colonists following the devastation of King Philip's War came to a head in the Revolutionary War. In particular, the taxes that England had levied against the colonies to pay for protection from the Indians and the French led to colonist demands for "No taxation without representation!", the catchphrase for pre-Revolutionary days.

If, as this book claims, major world events can be measured in 80-year cycles, why did 100 years pass between King Philip's War and the Revolutionary War?

The 80-year period is, of course, an estimate, and we could simply end discussion by saying that the interval we're discussing here was simply a little longer than average.

Still, it's interesting to analyze the situation, because there's valuable insight to be gained from understanding why the 80-year cycle was lengthened to 100 years.

The main factor was that England was on a different timetable. England had not experienced King Philip's War. Instead, England had been in a major war against its perennial enemy, France. That war, called the War of Spanish Succession (see page [westeurope#144]), was extremely brutal, and took place in Europe from 1701 to 1714. Following that war, England and France didn't fight another war until the 1790s, after the French Revolution. In between, England and France fought a number of mid-cycle skirmishes in other locations, including the colonies, but without having a serious crisis war.

So, the other factor delaying the American Revolution was the fact that the danger presented to the American colonists by the French and the Indians was quite real. Although England and France had temporarily ceased active warfare on the European continent, the two countries were still fighting proxy wars in America and India.

The largest of these wars in America occurred when the French formed an alliance with the American Indians, with the purpose of driving the English out of North America. The French had formed outposts in Canada, and south along the Mississippi River. The Seven Years' War ensued (known in America as the French and Indian War), from 1756 to 1763. France was decisively defeated not only in America but also in India, leaving England as the preeminent power in the world, by the time the two countries signed the Treaty of Paris in 1763.

Returning now to the question of why the Revolutionary War seems to have occurred some 20 years later than its "scheduled" time in the 1750s, we see that the colonists still desperately needed English protection from the French in the 1750s, and would not have wanted to risk a separation at that time. Without the French, the American Revolution might indeed have occurred 20 years earlier.

Once the Treaty of Paris was signed, the colonists were no longer in any danger from the French, and generational forces began to take hold. The English were, quite simply, no longer needed. The colonists grew increasingly hostile to English control, and especially objected to taxation without representation.

The British had other motivations. As soon as the treaty with France had been signed, they moved to consolidate their control over America as a British colony. In particular, the Sugar Act and Currency Act of 1764 were imposed in order to prevent the colonies from trading with any foreign country except through England as an intermediary. The Stamp Act of 1765 was enacted to recover at least a fraction of the money England had to spend to maintain its military forces in the colonies.

| The colonists needed England's protection from the French until 1763 |

These moves by England hardly seem unreasonable. The colonies were expensive children, and like a parent expecting his children to pay a little rent, England had a right to expect the colonists to pay for a portion of the cost of protecting them.

But the pressure for revolution had been building for a long time. The Stamp Act was particularly galling. All printed documents, including newspapers, broadsides and even legal documents, had to have stamp affixed, with the cost of the stamp being paid to England.

An underground terrorist group called the Sons of Liberty was formed. This group used violence to terrorize Stamp Act agents and British traders in numerous towns. However, violence was rare: colonial opposition was designed to be non-violent. The colonies formed a "Stamp Act congress" to call for repeal. English imports were boycotted.

Since this was a mid-cycle time period for England, the English sought merely to contain the problem and compromise. As a result, the Stamp Act was repealed by 1766.

However, England was still trying to find a way to collect revenue from the colonies without engendering riots, but they never succeeded. In 1767, England passed the Townshend Acts, imposing further taxes on goods imported to the colonies. Four more years of increasingly virulent protests force England to repeal the taxes in 1771.

There's no question that England was doing everything it could to compromise and contain the situation.

When occasional violence broke out, it was contained. In the most well known incident, the 1770 Boston Massacre, where British soldiers fired into a crowd and killed five colonists, two of the soldiers were tried and convicted, and tensions were relieved again.

By 1771, all taxes had been repealed except a tax on importation of tea, and even that tax was often evaded. From a purely objective view, the colonists really had few major grievances at this time.

As we've previously said, three factors are required for a major crisis war to break out: a generational change, then a period of financial crisis, then a series of provocative acts by both sides, each of which is a shock and surprise to the other side, and calls for retribution and retaliation.

The financial crisis occurred in July 1772, when the English banking

system suffered a major crash . Many colonial businesses were in

debt to the English banks, and were suddenly unable to obtain further

credit, forcing them to liquidate their inventories, thus ending

their businesses. Business conditions only improved with the start

of the war. We'll discuss this particular financial crisis further

in chapter 6.

. Many colonial businesses were in

debt to the English banks, and were suddenly unable to obtain further

credit, forcing them to liquidate their inventories, thus ending

their businesses. Business conditions only improved with the start

of the war. We'll discuss this particular financial crisis further

in chapter 6.

There's always an event that seems to electrify a society, leading up to a major war. Previous similar events have no major effect, but some particular new event causes a reaction way out of proportion to its seeming significance.

In May 1773, The English Parliament passed a new Tea Act, and in December 1773, a group of Boston activists dumped 342 casks of English tea into Boston Harbor.

This was simply another round of the same dance -- a new tax and a non-violent response. There was no reason for it to end any differently, except that now the country was in the middle of a financial crisis.

The response, known as the Boston Tea Party, has become world famous. It was so electrifying at the time that it surprised and shocked both the colonies and England. After that, one provocation after another on both sides finally led to war.

The furious English Parliament passed a series of "Coercive Acts" to dismantle the colonial Massachusetts government, close the port of Boston, and control the hostilities. This was tantamount to a declaration of war. With positions on both sides becoming increasingly hardened, war was not far off.

Hostilities actually began in April 1775, when the colonial minutemen attacked the British forces following the midnight ride of Paul Revere. The separation became official on July 4, 1776, when the Continental Congress endorsed the Declaration of Independence.

The war continued until November 30, 1782, when American and British representatives signed a peace agreement recognizing American independence.

The Revolutionary War was a crisis war for the colonies, but it was a mid-cycle war for England. This makes a big difference in the pursuit of a war. The Americans fought the war with great ferocity; the English fought the war halfheartedly.

(Think of our own war in Vietnam, where the North Vietnamese fought fiercely and won, while the American public supported the war half-heartedly.)

The American forces, under George Washington, fought for six years under the most brutal conditions. In a letter requesting more provisions, Washington wrote, "For some days past, there has been little less than a famine in camp. A part of the army has been a week, without any kind of flesh, and the rest for three or four days. Naked and starving as they are, we cannot enough admire the incomparable patience and fidelity of the soldiery...."

They could easily have given up at any time, and the country would have returned to being a British colony. But sheer momentum, sheer determination, kept the American forces going to victory.

| The British faced a very strong anti-war movement |

The British should have won. They had many more soldiers and vastly greater provisions. But they didn't have the ferocity that the Americans had.

In passing the Coercive Acts of 1774, England was effectively

declaring war on the colonies, but doing nothing to prepare for the

war. In fact, England did nothing to strengthen its forces in

America that year, and even actually reduced the size of its

Navy .

.

According to British General John Burgoyne, writing from Boston in 1775, "After a fatal procrastination, not only of vigorous measures but of preparations for such, we took a step as decisive as the passage of the Rubicon, and now find ourselves plunged at once in a most serious war without a single requisition, gunpowder excepted, for carrying it on."

Once the war began, there was a strong anti-war movement of sorts in

England . The King had difficulty recruiting soldiers, and

largely employed German mercenaries (Hessians) to fight against the

Americans. A loud, vocal English minority denounced the entire war,

and called for withdrawal.

. The King had difficulty recruiting soldiers, and

largely employed German mercenaries (Hessians) to fight against the

Americans. A loud, vocal English minority denounced the entire war,

and called for withdrawal.

England's time was not 1776. England's next major crisis began in 1793, with France and the French Revolution, and then England fought with great ferocity. That will be discussed in chapter 8.

The end of the Revolutionary War didn't mean the end of the American crisis. There were still grave doubts as to whether the Union could survive. The colonies had formed a very weak Confederation, which left each former colony largely autonomous, adopting its own currencies, taxes, laws and rules. The economy suffered a major recession in 1786, resulting in severe acts of terrorism by bankrupt farmers and businessmen -- acts that couldn't be controlled since the terrorists could not be pursued across state lines because there was no federal army. The crisis did not end until 1790, after the Constitution was ratified and George Washington became president.

We'll soon be jumping ahead to America's next great crisis war, the Civil War, but before we do that, we have to tie those two great wars together. And indeed, they are tied together by a single divisive issue: slavery.

The United States of America was formed because of a compromise that permitted slavery to exist in the South, though it was made illegal in the Northern states. This compromise in 1776 was necessary to form the nation in the first place, but it almost destroyed the Union in 1861. That's usually how any society goes from crisis war to crisis war. There may be other wars in between, but the crisis wars are usually tied together by a great compromise of some kind -- a compromise that ends one crisis war falls apart decades later and becomes the cause of the next crisis war.

The Republic of the United States of America was a "great experiment." Today we take our Republic for granted, but nothing like it had ever been tried before. Europe was filled with interlocking monarchies that started to come unraveled by the French Revolution that began in 1789, and thinkers were heavily influenced by the American Constitution in devising their own republics.

However, the usual "generation gap" that follows a crisis war was created. We've already discussed the transition from the Revolutionary war to the Civil War (see p. [basics#71]), so here we'll fill in some additional details.

The people who were involved in the creation of the Union considered it to be very fragile, and not certain to survive. This was the "older generation," people who witnessed the creation of the Union, spent the remainder of their lives doing everything in their power to hold the Union together.

However, those doubts about the Union were not shared by those born after 1790 or so. To the "young generation," the Union was a fait accompli. They had no personal experience of the doubts that the Union could be created, and so they took the Union for granted. As a result, their concerns turned to new areas.

These concerns blossomed in the awakening (and the social turmoil) of the 1820s and 30s, when this new generation grew into adulthood. Women's rights began to be seriously addressed at this time. And, as with the previous awakening, there were heavy religious overtones, with many evangelists holding "revivals," telling people how to revive their sinful souls from damnation.

However, the greatest turmoil arose out of the slavery issue. Slave rebellions began to develop, especially in those parts of the South where blacks outnumbered whites. The fiercest was the 1831 revolt led by black slave Nat Turner, who had been born in 1800. Turner's rebellion resulted in the deaths or massacres of dozens of whites and blacks, until Turner himself was hanged several weeks later.

As I study the events leading up to each cataclysmic war in the cycles of history, I always get the feeling of a kind of "pressure cooker" of resentment and anger building up over decades of time, until finally the pressure cooker explodes into war.

It's hard not to feel this pressure cooker effect in reading about the abolitionist movement of the first decades of the 1800s. The Northern abolitionists became increasingly determined to see slavery abolished, and the Southerners became increasingly defensive and less willing to compromise their need for black slaves to harvest cotton.

In the midst of it all were the Unionists, the cautious men on both sides of the slavery issue who wanted to compromise and contain the problem. These were mostly people in the older generation, born before 1790. Some supported slavery and some opposed slavery, but all of them made slavery secondary to the most important goal of all: Saving the Union.

As the people in the older generation retired or died, the new generation, which took the Union for granted, began to assume power. Some in the new generation supported slavery, and some opposed slavery, but these people were different: For them, the Union was a given, and there was no more important issue than slavery itself.

As long as the older generation held power in Congress, compromise was king. And the lengths to which the Congress went to maintain the compromise would be considered almost comical, if they weren't about such a serious subject.

The juggling game that went on was to keep the number of "slave states" equal to the number of "free states." As states were added to the Union throughout the early 1800s, this balance had to be maintained. Thus, the "Missouri Compromise" of 1820 admitted Missouri as a slave state, simultaneously with Maine as a free state. The huge Louisiana Purchase was split into slave and free regions.

Other artifices were used as well. In 1836, the House of Representatives adopted a "gag rule," which prohibited discussion of any bills that involved the issue of slavery in any way. This gag rule continued through 1844.

The last great Unionist Senator was Henry Clay. Born in Virginia in 1777, he spent his entire life in efforts to preserve the Union. He sponsored and brokered compromise after compromise to keep the slavery issue contained. Indeed, the last great speech of his career, given to the Senate in 1850, urged a major compromise that included admitting California to the Union as a free state. He was joined in this effort by a fierce opponent, the vehemently anti-slavery Massachusetts Senator Daniel Webster, born in 1782. They were fierce political opponents and both great orators, but in March 1850, they stood together to support one more major compromise to preserve the Union. These are the kinds of compromises that are standard fare during an "unraveling" period. These men both died in 1852, and there were no further "great compromises."

For the next few years, the slavery issue was contained. One event of note was the formation of a new third party -- the Republican Party -- in 1854, to promote abolition from a political point of view. For the next century, the Republican Party would be identified as the anti-slavery party, and the Democratic Party would be stigmatized as the party sympathetic to slavery.

As we've previously said, three factors are required for a major crisis war to break out: a generational change, then a period of financial crisis, then a series of provocative acts by both sides, each of which is a shock and surprise to the other side, and calls for retribution, justice and retaliation.

The financial crisis occurred in August 1857, when the New York branch of the Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Company failed. Almost 5,000 businesses failed in the resulting Panic of 1857. This primarily affected the industrialized North, since the South's cotton was still in demand, and increased the North's resentment against the South and against slavery. The depression in the North continued well into the 1860s, and was one of the primary factors motivating the anti-draft riots in New York City -- the riots occurred in high unemployment areas by people who were afraid that freed slaves would take the few jobs they had.

In October 1859, abolitionist John Brown (born in 1800) seized the

Federal arsenal at Harper's Ferry in order to protest slavery. His

intention was to spur a massive slave insurrection or even a civil

war that would end slavery . (Incidentally, this was similar to

the reason Osama bin Laden gave for the 9/11 terrorist attacks: To

provoke a worldwide war between Muslims and the infidels.) He was

tried for criminal conspiracy and treason, convicted and hanged. This

sequence of events polarized the entire country, and inspired the

Northern troops' Civil War anthem, "John Brown's Body Lies

A'mouldering in the Grave." Even today, I've heard southerners refer

to John Brown as a "murdering menace to society."

. (Incidentally, this was similar to

the reason Osama bin Laden gave for the 9/11 terrorist attacks: To

provoke a worldwide war between Muslims and the infidels.) He was

tried for criminal conspiracy and treason, convicted and hanged. This

sequence of events polarized the entire country, and inspired the

Northern troops' Civil War anthem, "John Brown's Body Lies

A'mouldering in the Grave." Even today, I've heard southerners refer

to John Brown as a "murdering menace to society."

This was not the first violent act committed by abolitionists; in fact, John Brown himself had committed some in the past. But with the national mood transformed by a generational change and a financial crisis, the Harper's Ferry raid electrified the nation, and hardened positions in both the North and the South.

From a purely objective point of view, there's no reason why the election of Abraham Lincoln as President in 1860 should have triggered the Civil War. It's true that he was opposed to slavery, and would never agree to extend it, but he also made it clear that he would not do away with slavery in those states where it already existed. Even after the Civil War started, he wrote that he would abolish slavery if it would save the Union, keep slavery if it would save the Union, or amend slavery if it would save the Union. At some other time in history, compromise might have contained the situation. But now, with a generational change and a financial crisis in play, things deteriorated quickly.

South Carolina voted to secede from the Union right away, in December 1860. By the time of Lincoln's inauguration, on March 4, 1861, seven Southern states had formed the Confederate States of America. The war began on April 12, when South Carolina forces fired on the federal troops at Fort Sumter.

The Civil War was devastating, and filled with atrocities. In the Battle of Gettysburg alone, there were 28,000 rebel casualties and 23,000 Union casualties. All told, there were hundreds of thousands of deaths -- a rate of 823 deaths per 100,000 of population, the highest ratio of any war in American history (though only half the rate of the pre-revolutionary King Philip's war).

What were the "causes" of the Civil War?

Slavery was certainly a big issue at the time, but it's hard to see why slavery was the cause of the Civil War.

After all, Lincoln did not intend to abolish slavery before the war, or even well into the war. Even if he had wanted to, the Congress could not have done it as long as the Southern states were voting. The only reason that slavery was abolished is because the Southern states had seceded and couldn't prevent it.

As I get older, I tend to get increasingly cynical about many things, including the causes of war. I see money as the cause of most things, and great, lofty ideals as mere rationalizations that come after the fact. The Panic of 1857 caused a lot of hardship, and the people of the North and South blamed each other. It's as accurate to say that the Panic of 1857 caused the war, as it is to say that slavery caused the war.

What about timing? If slavery was the cause, why didn't the war occur in 1830 or 1890 instead of 1860?

That's where Generational Dynamics provides an answer. The war occurred in 1860 because that's when the generational change occurred, approximately 80 years after the start of the Revolutionary War.

This shows how causes and timing work together to produce crisis wars.

This question, which is rarely discussed, is possibly one of the most important we'll consider. Why didn't the Civil War result in a hostile fault line between the victorious North and the resentful South, ending in a new Civil War 80 years later?

First, it's worth noting that the end of the war did not bring the end of the crisis.

The slaves were freed, but they had no place to live and few rights as citizens. The Reconstruction period was so brutal, it was almost a continuation of the war. Following Lincoln's assassination, President Johnson took political control of some of the Southern states, and kept troops stationed to enforce voting rights for blacks. Southern states continued to resist full integration of the blacks, passing laws that restricted the freedom of blacks.

The South was extremely bitter, not only because emancipation had been forced down their throats, but also because there was so much financial corruption and abuse during the Reconstruction. The Civil War crisis did not really end until 1877, when the last Federal troops policing the South were withdrawn.

There was no "great compromise" coming out of the Civil War. The North achieved all its objectives -- the seceding states were forced to return to the Union under the terms specified by the North -- including the full abolition of slavery. So why wasn't there a new Civil War 80 years later?

Scholars can debate this question (and, I believe, should debate it more than they have), but in my opinion, it's because of the flexibility of the American constitutional system, especially the Supreme Court.

Many people blame the Civil War on an 1857 Supreme Court decision known as the Dred Scott decision, wherein the Court ruled, in essence, that Dred Scott, a black man, was property and not a human being in the meaning of the Constitution. Many people believe that the Civil War could have been avoided if the Dred Scott decision had been made in the opposite direction.

I don't agree with that view. The Dred Scott case came far too late to have any effect one way or the other on the war.

Nonetheless, the Dred Scott case has served as a permanent reminder to the Justices of the Supreme Court that their highest objective is keep the Union safe. By being an "activist" court at the right times in history, the Court can release some of the pressure leading the country to a new Civil War, or to putting the country in danger in other ways. (My personal belief is that the Court intervened in the 2000 Presidential election for exactly this reason. The back-and-forth lawsuits could have gone on for months, leaving the country with no President at all for several months. The Court learned its lesson from Dred Scott and felt it had no choice but to intervene, and end the Presidential election once and for all.)

Incidentally, there's another example of a Civil War that did not lead to Civil War II: The English Civil War of the 1640s (page [westeurope#95]). The English government became flexible enough to allow for the "Glorious Revolution" of 1689, which permitted a major change in government with no blood shed. England has fought in many wars since then, but never another civil war.

Before 1800, the world's leading industrial power was France. But the Industrial Revolution that took place in England in the late 1700s and early 1800s made that country the leader by 1850. By 1900, the leading industrial power in the world would be the United States. How did that happen?

The industrial revolution jumped from England to America in earnest with the end of the Civil War.

It was a time of laissez-faire capitalism, with the public tolerating almost no regulations or restraints on business at all.

This was understandable; after all, slavery had been possible because the federal government had made it possible. The opposite of slavery is freedom, and so the post-war sentiment was that the federal government should not interfere with anyone's freedom. Any regulations or restrictions on anybody would have been just a short step on the slippery slope back to slavery.

The laissez-faire atmosphere permitted the accumulation of some great fortunes, especially through the building of the railroads. By 1900, building railroads also created enormous fortunes for people like J. P. Morgan and J. D. Rockefeller, who controlled more assets and had more income than the federal government. Such an idea would be recognized with horror today, but it wasn't even strange back then: it had never been the founders' intentions that the federal government be large or wealthy.

Other inventions dramatically changed American life: Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone in 1876, and Thomas Edison invented the incandescent light bulb in 1879. Both inventions became quickly very popular, and played major parts in the success of America as an industrial nation.

Awakenings tend to focus on social issues and social injustice; young people, who do not have personal memory of the previous crisis, rebel against the austere restrictions imposed by their elders whose only motivation is that "nothing like that should ever happen again."

In this case, the austere restrictions were, ironically, almost complete freedom from government: the federal government must never enslave anyone again.

The awakening, then, was led by people who reacted against the injustices of nearly complete freedom from government. (Once again, we can't help but note the irony of this statement.)

These reactions mainly focused on the trade unions (or labor unions). If the government were not going to prevent the capitalists from controlling all the wealth, then the workers would do so through the (often pro-socialist) labor unions. The 1886 labor rally in Chicago's Haymarket Square, in which someone bombed the policemen trying to control the crowd, terrorized the nation's people, and focused people on their grievances.

The extremes of capitalism's order and socialism's terror gave rise to a new movement called "progressivism," under whose banner some reforms were made, including legislation to do these things: provide for rights of workers to join labor unions; break up large businesses with anti-trust or "trust busting" regulations; and make it easier for ordinary citizens to own shares of stock. Other laws provided for consumer protection, women and child protection, and income tax collection. Further changes brought women's suffrage in 1918.

The arts played an important part in this awakening as well. Symphony orchestras and arts museums sprang up in cities around the country, and new architectural ideas of Frank Lloyd Wright and others were used in homes and buildings throughout the country.

At this point, it's worthwhile to stop and consider why World War I was not a crisis war for the United States.

A question is frequently asked: Why is World War II considered to be a crisis war, but World War I is considered to be a mid-cycle war?

WW I was not a major war for the United States. One way that this is indicated is by the number of people killed in battle: The figure as a percentage of population was substantially lower for World War I than for the crisis wars (Revolutionary War, Civil War, WW II), as the following table shows:

Courier

Deaths

War Pop(M) Deaths per 100K Crisis?

--------------------------- ------ ------- -------- -------

King Philip's War (1675-76) 0.05 800 1538 Yes

Revolutionary War (1775-83) 2.5 4,435 177.4 Yes

War of 1812 (1812-15) 9.8 2,260 23.6

Mexican War (1846-48) 23.2 1,733 7.5

Civil War (1861-65) 34.4 283,394 823.8 Yes

Spanish-American War (1898) 76.2 385 0.5

World War I (1917-18) 100 53,513 53.5

World War II (1941-46) 132 292,131 221.3 Yes

Korean War (1950-53) 151 33,667 22.3

Vietnam War (1964-73) 203 47,393 23.3

Persian Gulf War (1991) 249 148 0.1

However, number of soldiers killed is only one of many considerations in deciding whether a war is a "crisis war" (see page [localization2#84]). What's the difference?

In our studies, we've found that we can summarize the difference between crisis wars and mid-cycle wars in the concepts of "energy" and "transformation."

I mentioned earlier, in conjunction with the Civil War, that it's possible to feel a kind of "pressure cooker" of resentment and anger building up over decades of time, until finally the pressure cooker explodes into war. If the pressure in the pressure cooker is great, then the country almost explodes into war; otherwise, the country dribbles into war. If a country pursues a war with a great deal of energy, then it's a crisis war; if not, then it occurs at some other point in the 80-year cycle. After the war is over, signs that indicate a major transformation of society are major changes in the way the society is governed, whether national boundaries change or populations are displaced. None of that applied to America and World War I.

America entered WW I only very reluctantly.

America was actually neutral to the war when it first began in 1914, and Americans themselves were often split in their sentiments along ethnic lines. Americans were shocked when the British passenger ship Lusitania was sunk by German submarines in 1915, killing thousands of people including 114 Americans, but not shocked enough to enter the war, or to change its neutrality.

President Wilson's own sentiments leaned toward the side of the Allies (England and France) against Germany, but a strong pacifist (anti-war) movement forced him to proceed cautiously. In fact, America continued to provide goods and services to both the Allies and Germany, until it finally entered the war in 1917.

America stayed neutral despite numerous German terrorist attacks on Americans, and against American citizens. German subroutines sank an American freighter, as well as British, French and Italian passenger ships, killing thousands of civilians including hundreds of Americans. A German exploded a bomb in the U.S. Senate reception room. President Wilson's own Secretary of State, William Jennings Bryan, resigned in protest when Wilson merely sent a protest note to the Germans. Bryan then headed a pacifist group that vigorously opposed American's involvement in the war, and used Senate filibusters to prevent America from challenging Germany in any significant way.

In January 1917, Wilson outlined a peace plan, calling for "Peace without victory." Germany's response was to sink several American steamships without warning. Only then did America finally declare war on Germany in March 1917.

Furthermore, WW I didn't really change anything in America. Reparations were imposed on Germany, but they were lifted quickly. The League of Nations was created, but America didn't join.

WW II was very different. We were on the side of Britain before we even entered the war, and we declared war immediately when Pearl Harbor was bombed. America was completely transformed by WW II -- in that we accepted the mantle of "policemen of the world." Not only did we form the United Nations and join it, but also we headquartered it in New York. We used the Marshall Plan to help rebuild Europe, and we took over the government of Japan for a few years.

It's this enormous difference in "energy" that separates a crisis war from a mid-cycle war.

Those who remember the Vietnam War remember how divided we were as a country. That was another mid-cycle war for us, and one of the reasons we lost is because we didn't have the energy to support our troops in Vietnam. The North Vietnamese forces were far more energetic than we were because it was a crisis war for them.

Contrast that to America's response when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor -- we declared war the next day, and mobilized against Japan and Germany without hesitation. There was a pacifist movement, but it was completely ineffectual.

Contrast it also to America's response to the 9/11/01 attacks. We declared war against Afghanistan within a month, and President Bush is receiving overwhelming public support for military actions there and against Iraq.

Reading the above examples, you begin to see what "energy" means. The United States was not anxious to get into WW I. There was constant dithering and debate, in the face of numerous terrorist acts.

So if WW I was not a crisis war, why do historians why was it called the "war to end all wars" when it happened, and why do historians call it one of the worst wars in history?

The answer is that WW I and WW II are different timelines. WW II was a west European war, while WW I was an east European war.

We'll be discussing World War I in chapter 4, but here's a summary. WW I was a crisis war for several east European countries, two of them in particular:

As you can see, what came out of World War I is profoundly affecting the world today. It's possible that America's timeline will merge with the Islamic timeline, and the much-discussed "clash of civilizations" between the West and Islam will be a crisis war for both sides. This scenario will be discussed in chapter 4.

The Great Depression and World War II go together -- it's impossible to understand one without the other. We're going to be studying the Great Depression in detail in chapter 6, but for now let's look at its part in leading to World War II.

Research seems to indicate that a financial crisis and a war crisis seem to feed on each other and make each other worse: A financial crisis makes people restless and angry, looking for a scapegoat, for justice and retribution, making a war crisis worse; and a war crisis makes people financially risk aversive, less willing to make purchases and investments, making the financial crisis worse.

There seems to be plenty of evidence that the Great Depression was a major factor in providing the energy for World War II. When a person loses his job or his home, he'll get angry with his former boss or the bank that foreclosed on him.

When a society goes through a recession, the people look to their own government leaders to blame.

When the recession gets very bad, to the point of a depression, then jealousy can set in, and the desire for justice and retribution becomes enormous. A nation might start thinking about how great things are on the other side of the border. This is the kind of thing we've already seen in the Civil War: the Panic of 1857 devastated northern businesses, but hardly had any effect at all on the cotton farms of the south, especially in view of the free slave labor.

When a financial crisis gets so bad that many people are starving and homeless, a war becomes much more desirable. If you're starving you really have nothing to lose by going to war, and becoming a soldier may be the only way to get food and shelter, and to feed your wife and children.

Now let's see how the Great Depression was an integral part of the steps that led to World War II.

Perfectly reasonable acts by one country can be interpreted as hostile acts by another country. Guns and bombs are not needed to create an impression of war.

And if one country's innocent act is a shock to another country and is viewed as hostile by that country, and if the people of that country are in a mood for retribution rather than compromise, than they may well look for a way to retaliate.

In that sense, the enactment of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act in June 1930, can be viewed as the first of the shocking, provocative acts that led to World War II.

The Act was opposed by an enormous number of economists as being harmful to everyone, but it was very popular with the public, because of the perception that it would save American jobs. Many in the public believed that the crash had been caused by withdrawal of investment funds by foreign banks, just as many in the public today believe that the Nasdaq crash of 2000 was caused by the illegal or improper actions of CEOs of Enron and other corporations. The public demanded the Smoot-Hawley Act in retribution, just as the public today demands the jailing of corporate CEOs.

Interestingly, the Smoot-Hawley Act is still debated by politicians today, with regard to whether it caused or aggravated the Great Depression or had no effect, with pro-free trade politicians taking the first position, and politicians supporting restrictions on free trade taking the second position.

Those discussions are entirely America-centric because, for the purposes of this book, it makes no difference whatsoever whether or not the Act aggravated the American depression. We're interested in the effect it had on foreign nations.

And the effects were enormous. The bill erected large trade barriers for numerous products, with the intention of saving American jobs. How many American jobs it saved, if any, is unknown, but it virtually shut down product exports to the United States. Both Germany and Japan were going through the same financial crisis America was going through, and they were furious that America as a market was closed to them.

Japan was the hardest hit. The Great Depression was hurting Japan

just as much as it was hurting America but, in addition, Japan's

exports of its biggest cash crop, silk, to America were almost

completely cut off by the Smoot-Hawley Act . Furthermore,

Japan would have been going through a generational change: The country

had undergone a historic revolution some 70+ years earlier,

culminating in a major change of government (the Meiji Restoration) in

1868, and the people who had lived through that revolution would be

dead or retiring by the early 1930s.

. Furthermore,

Japan would have been going through a generational change: The country

had undergone a historic revolution some 70+ years earlier,

culminating in a major change of government (the Meiji Restoration) in

1868, and the people who had lived through that revolution would be

dead or retiring by the early 1930s.

So one thing led to another, and in September 1931, almost exactly a year after Smoot-Hawley, Japan invaded Manchuria and later northern China. Britain and American strongly protested this aggression, and Roosevelt finally responded with an oil embargo against Japan.

This is the usual pattern of provocative acts on both sides. America saw Smoot-Hawley as its own business, but to Japan it was a hostile shock. Japan saw the Manchuria invasion as "Asian business," while Britain and America saw it as attacking their own Asian interests. Roosevelt saw an oil embargo as a measured response of containment, while energy-dependent Japan saw it almost as an act of war, eventually triggering Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941.

Japan wasn't the only country affected, of course. England, Germany, Italy, and many other countries were hit hard by the sudden trade barriers with America. Just like in Japan, nationalistic and militaristic feelings were aroused in many countries.

Germany was especially frustrated. The map of Central Europe had been redrawn some 70 years earlier during a series of wars in the 1860s, culminating in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, and the unification of Germany in 1871. The Great War (WW I) had been a mid-cycle war for Germany, and had been a humiliating defeat, especially because the American and British led Allies had imposed harsh conditions -- the loss of some German-speaking territories, and the payment of reparations. The loss of territories was especially provocative, since it partially reversed the German unification of 1871.

Germany was reaching the point where it was going to explode anyway, when the Smoot-Hawley Act was passed. On top of the reparations, the Act was seen as enormously hostile by the Germans. As in Japan, it gave rise to militaristic nationalism in the form of the rise of the Nazis. Germany remilitarized its border with France in 1936, and then annexed German-speaking parts of Eastern Europe in 1938.

So when did World War II start? It depends on what the word "start" means, but an argument can be made that American had started the war, and that the first act of war was the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act.

The Central European wars of the 1860s were renewed in full force when Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, causing France and England to declare war. Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941, causing America to declare war on the Japan / Germany / Italy Axis.

Russia ended up playing a big part in World War II, but not by choice, since it was a mid-cycle war for the Russians. Still exhausted from World War I and the Bolshevik Revolution, Russian dictator Josef Stalin tried to stay neutral, but was forced into it when Hitler invaded Russia. Ironically, this invasion was Hitler's undoing -- the irony being in the fact that Napoleon was similarly undone when he invaded Russia in 1812, in a remarkable war that was also mid-cycle for Russia (see chapter 5).

Many people believe that Hitler was a unique monster who caused World War II. This belief is usually stated as: "If only we had killed Hitler in 1935, then we could have avoided World War II."

In fact, when I discuss this book with people, that's possible the biggest criticism I hear, since this book essentially claims that World War II would have occurred with or without Hitler. "How could World War II ever have happened without Hitler?" people ask.

Well first off, Hitler never attacked America: Japan did. What did Hitler have to do with that?

Second, Hitler didn't even attack Britain and France until they attacked Germany.

Third, the early conflicts of World War II were well under way before Hitler invaded anyone. Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931, and Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935. Hitler's reoccupation of the Rhineland came later, in 1936, and was standard fare for Europe for centuries.

Fourth, Germany has been having wars with France and England literally for centuries. Hitler didn't cause those, so why should this one be blamed specifically on him?

Fifth, Hitler only assumed absolute power in Germany when a specific generational change took place: the death of the President of Germany, Paul von Hindenburg.

Von Hindenburg was born in 1847, and he'd fought in the convulsive wars of the 1860s that created the German union. He was a national hero, and became President in 1925. It was only on his death in 1934 that Hitler was able to overthrow constitutional government,

Germany was like a pressure cooker, ready to explode. Hitler was the agent that brought about one portion of World War II, but he was not the cause of World War II, or even the cause of Germany's part in World War II. All the factors pushing Germany towards war were in place before Hitler's rise to power.

There's one more question that people ask about Hitler: "But even if you're right and World War II would have occurred anyway, at least someone else wouldn't have committed genocide of the Jews. Hitler was a unique monster to have done that."

Well, if you think that, you're wrong. You may say that Hitler was a monster, and you would be right, but he was far from unique.

Genocide was quite commonplace in European wars, which have seen genocide against Jews, Muslims, Christians, and probably other groups as well. Furthermore, there was a history in particular of genocide of the Jews going back many centuries. Finally, genocide is hardly unique to Germany. Worldwide in the 20th century, there have been close to a dozen cases of genocide where a million or more people have been killed on purpose. Genocide is going on today.

So there's no particular reason to believe that things would have been any different if some other leader besides Hitler had taken over after von Hindenburg died. Hitler was a monster, but he was really just an ordinary monster.

The aftermath of World War II brought a startling change to the Western world.

For hundreds of years, the Western world was dominated by various European powers -- Spain, France, Britain or Germany at different times. As a result, the nations of Europe were always poised to fight with one another: on the Continent in crisis wars, and around the world in mid-cycle wars over various colonies.

Following World War II, this multitude of national powers was replaced by just two major superpowers: the United States of America on one hand, and the USSR (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics or Soviet Union for short) on the other hand.

However, the situation was more complex than that because World War II was a crisis war for America and Western Europe, but was a mid-cycle war for Russia. These facts affected the interplay of the two superpowers.

The negotiations to settle World War II involved four nations: America, Britain, France and Russia (the USSR).

The three countries of the west had been through a crisis war, and were willing to accept compromises to end the war, provided that "nothing like this must ever happen again."

Russia was "in a different place." Russia had gone through a huge civil war during the 1920s and 30s, with Josef Stalin's faction winning. This was followed by millions of deaths by starvation and execution as Stalin transformed the country in the world's first Communist nation.

Stalin himself was a highly ideological Communist. He claimed to believe that the world would never be at peace until the entire world was Communist.

Stalin's plan was to convert the world to Communism. So World War II was not a crisis war to him; instead, it was an opportunity to spread Communism to other countries.

The contrast in their attitudes gave Stalin an advantage over the west in negotiations. The West was anxious for Stalin's help against Hitler, so Stalin could manipulate the terms.

Germany and Russia had fought two world wars. Stalin insisted on being given a "buffer region" to protect itself from another war with Germany.

In 1945, Stalin was given control of numerous countries in Eastern Europe on condition that they have free elections. These countries included one-fourth of Germany itself, to be known as East Germany.

Winston Churchill was the first to recognize what was really going on, and that Stalin had snookered the West, when he said, "an iron curtain has descended across the continent." It took another year for the public at large to understand as well.

Stalin intended to use military force in each of these countries and convert it to Communism.

That set the framework for Europe for decades to come. Europe was partitioned into a Western region, consisting of democracies, and Eastern region, consisting of Communist dictatorships, all behind the Iron Curtain.

By commandeering the resources of the East European countries, Russia became a second superpower, alongside the United States.

For decades, the "Cold War" referred to the struggle between Western democracy and Soviet Communism. It was called a Cold War for the obvious reason -- the West and the Soviets never actually launched their respective nuclear-tipped intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs).

However, Russia was on an earlier timeline than the West, and so its next crisis began in the 1980s; the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991.

The Korean and Vietnam wars are examples of what I call "momentum wars": They're mid-cycle wars, so they aren't fought with a great deal of energy, but they're fought with the same justification as the preceding crisis war. These wars occur because of the momentum created by the previous crisis war, but the public has no real desire to fight them.

By the late 1940s, the attitude in the West was that it had been snookered twice, by two different violent dictators, Hitler and Stalin:

These were bitter discoveries for the generation that had fought a bloody war to save Europe from Hitler. "If only we'd stopped Hitler earlier, if only we hadn't appeased him," the reasoning went, "we might have been able to prevent World War II. Let's not make the same mistake with Stalin."

The first battleground was Korea. Following the war, Russia occupied North Korea and America occupied the South. In 1950, North Korea invaded South Korea under Russian direction. America was committed to stopping Russia before another mistake was made (as mistakes with Hitler and Stalin had been made before). The Korean War ended in a stalemate in 1953.

In the 1950s, it seemed to the people who had fought in World War II that they had defeated Hitler and the Nazis, but were losing to Stalin and the Communists. Even after Stalin died in 1953, the news seemed all bad. China under Mao Zedong had also become Communist, and was allied with Russia. And Russia was continuing to consolidate its hold on Eastern Europe's nations as Communist satellites of Russia.

It should now be possible to see the massive generational conflict that occurred in America during the 1960s and 70s, centered on the Vietnam War in Southeast Asia.

The previous crisis war in Southeast Asia had been between the French and the Chinese in the 1880s and 1890s (see p. [asia#133]). After World War II, the French were driven out of Vietnam, and Vietnam became partitioned -- like North and South Korea -- into Communist-controlled North Vietnam and Western-aligned South Vietnam. As in Korea, America intervened to prevent North Korea from conquering South Vietnam.

By the time of the mid 1960s, a generational change had occurred.

I would be surprised if more than 1% of all kids born after 1940 or so had the vaguest idea where Vietnam was, prior to the mid-1960s, or even knew anything at all about Southeast Asia.

This is the heart of the "generation gap" that we've been discussing. The people who had fought with their blood and their lives to stop the Nazis, and didn't want to see anything like that happen again with the Communists, were horrified to see the Communists succeed where the Nazis had failed.

But the kids with no personal memory of WW II felt no such horror. They couldn't see any point in fighting the Vietnam War, and this fomented the intergenerational rebellion that occurred in the 60s and 70s.

The heroes who fought in World War II have every reason to feel very bitter about how they were treated. It's true that they returned to parades that glorified them in 1945, but that glory didn't last forever.

The generation of heroes that fought in WW II were tremendously humiliated by the antiwar movement in the 60s and 70s. The older generation was treated as evil incarnate, though their goals were no more venal than a desire to prevent World War III against the Communists. Instead of being praised for this effort, they were disgraced. The natural reaction was, "OK, if you don't want to have any wars, then let's not have any wars."

This gave rise to what was called, "the Vietnam Syndrome," the fear of being humiliated again by another war.

By the time of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the heroes who had fought in WW II were long gone, and the kids who grew up during WW II were mostly dead or retired.

What generation was left in charge? The generation that had rebelled in the 60s and 70s; the generation that had humiliated the previous generation of war heroes; the generation that was sure it knew, better than anyone else, when war was "right" and when war was "wrong"; the generation that had no personal experience with WW II.

This generation had been very well protected by the heroes of WW II, and their wisdom guided the country through decades of danger.

Now we're being guided by people with much less appreciation for the dangers that the world holds -- both the dangers of war, and the dangers of failing to stand up to monster dictators. America's destiny for the next decades will be determined by the wisdom of this new generation.

Just as an individual has a character, a nation also has a character. And just as a crisis can force an individual to change from sinner to saint, or vice versa, a crisis war can cause a nation to change its character in a significant way.

America has changed its character after every crisis war. It's almost as if America has been several different nations. Here's a summary:

We can only guess what kind of nation America will be after the next world war.

In the worst-case scenario, where America is ravaged by nuclear weapons, disease, and foreign bombs, American might be a beaten nation, no longer a superpower, just struggling for survival.

In the best-case scenario, where America's isolation protects it, as it has before, so that the war never really reaches America's soil, then America may yet again be the world's leading superpower.

Mexico is not covered elsewhere in this book, but there are some important things about Mexico that Americans need to know.

Mexico's last crisis war was the Mexican Revolution, which began in 1910 with an insurrection against dictator Porfirio Díaz. The insurrection grew into a massive civil war that lasted into the early 1920s.

Today, Mexico appears to have entered a new crisis period, although no new crisis war has occurred yet. The country came through a massive financial crisis it suffered in 1994, but economic problems are still severe, with big areas of poverty and unemployment.

This is important to America because of the number of Mexican

immigrants in America, especially in California. Some 10 million of

California's 35 million people -- almost 1/3 -- are Mexican

immigrants, 70% of them illegal . Mexicans in California make

far less than native Californians, and use far more in public

services, including welfare programs.

. Mexicans in California make

far less than native Californians, and use far more in public

services, including welfare programs.

The result is that a major fault line has developed between Americans and Mexicans, in California and across the border. In a new Mexican crisis war, the war will almost certainly engulf parts of California, and other southern states may be involved as well.

A crisis war transforms a country, gives the country a new character, and makes it a different country than it was before the crisis war. World War II transformed America completely, changing it from a laissez-faire economy to a heavily regulated economy, and from an isolationist nation to the Policemen of the World, with things like the United Nations and the Marshall Plan. This 70-80 cycle may well be known in history as "The Golden Age of America."

In the space of a few years, America's role as Policeman of the World has changed from a defensive role to a preemptive role. This is President Bush's stated policy, and it's fully supported by the American people, where it wouldn't have been, just a few years ago.