Dynamics

|

Generational Dynamics |

| Forecasting America's Destiny ... and the World's | |

| HOME WEB LOG COUNTRY WIKI COMMENT FORUM DOWNLOADS ABOUT | |

|

These pages contain the complete manuscript of the new book

Generational Dynamics: Forecasting America's Destiny,

written by John J. Xenakis.

This text is fully copyrighted. You may copy or print out this

material for your own use, but not for distribution to others.

Comments are invited. Send them to mailto:comments@generationaldynamics.com. |

Although the American heritage is mostly European, Asia has recently played an enormous role in the lives of ordinary Americans -- the Japanese attack on the United states that led us into World War II, the war in Vietnam, and the American-Japan economic relationship of the last few decades have all assumed major importance recently.

The generational methodology provides some unique insights into both Japan and Vietnam -- insights that are not mentioned in standard histories of these countries.

And in the case of China, we'll apply some trend forecasting and mathematical complexity techniques, recognizing that with 1.4 billion people, the mathematics of infinity really begins to apply.

We present a history of China since roughly 1800.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

There have been two crisis wars since that time, both of them civil wars:

In addition, we'll discuss some mid-cycle wars with England and Japan.

China is a very interesting example of the methodologies being described in this book because of its size and its relative isolation. When mathematicians talk about the "complexity" of doing something, there's always a background concept that can be stated as: how complex is it to do something as the number of objects you're handling approaches infinity?

Well, guess what? For most practical purposes, the number of people in China is about as close to infinity as we're going to get.

When you're talking about smaller societies, a government can avoid the complexities of governing by numerous ad hoc measures, such as building larger bureaucracies to handle problems.

But when you have 1.4 billion people, as China does today, there are no ad hoc methods to speak of. Almost every governance technique that might be used with that many people can be modeled mathematically and shown to be inadequate.

It's natural to analyze China's history in the usual way -- struggles between brilliant and stupid leaders, wars triggered by bad weather or aggressive outsiders, and so forth.

Out treatment will be quite different. We're going to use our new tools -- trend extrapolation and complexity analysis -- to sort which of China's problems in the last two centuries were man-made, and which of them would have to have happened one way or another.

Here is the basic outline:

That's the outline of what had to happen, one way or another, to China since 1800. Now let's see how these events actually played out.

While European nations are at most a few hundred years old, China has been identifiable as a nation for over 2,000 years. How could such a vast, populous territory be managed and governed? What is the paste that held this nation together all this time?

The answer would have to be a relatively homogeneous population (that is, no major fault lines along religious or ethnic lines), and Confucianism, an ingenious religion, philosophy, and set of social rules. It gave each person a specific place in society, and defined specific duties and modes of conduct. For example, it defined Five Relationships of superiors over inferiors: prince over subject; father over son; husband over wife; elder brother over younger brother; and friend over friend. As long as each individual knew his place, and knew how to act, it would not be necessary for someone else to direct his activities, thus simplifying government.

As China was ruled alternately by warriors of different regions, or dynasties, all were tied together by the rules devised by Confucius in the fifth century BC. In the last thousand years, for example, China was ruled by warriors from Mongolia (1271-1368) in the north, from the south of China (1368-1644), and then from the north again by warriors from Manchuria (1644-1912).

|

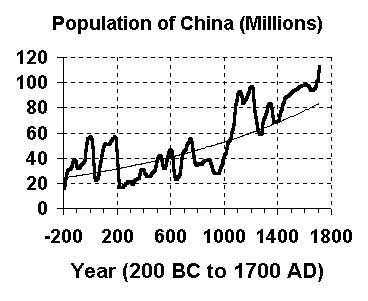

However, as this graph shows, the population of China has had wild swings throughout its history. It's hard for contemporary Americans to even imagine this, but wars, famine and disease have, at various times, killed tens of millions of Chinese people in a relatively short period of time.

The complexity of managing China's huge population is inescapable. China is geographically slightly smaller than the US, but has almost five times the population -- 1.3 billion people. When you're dealing with numbers that large then, like it or not, the full force of mathematical complexity theory must be applied in order to make sense of what's going on and what happens to be done.

Even in 1800, China had about 400 million people -- 300 million

farmers, plus 80-100 million city folk: artisans, merchants,

landlords, scholars and government officials .

.

That's why, even as late as the year 1800, a typical Chinese village

pretty much took care of itself -- handling contracts, real estate

transfers, boundary disputes, and organizing collective actions such

as irrigation projects or business enterprises -- without reference

to any government officials

-- handling contracts, real estate

transfers, boundary disputes, and organizing collective actions such

as irrigation projects or business enterprises -- without reference

to any government officials .

.

This is the heart of low-complexity government: Keep all decision making, as much as possible, at the village level. As soon as you try to centralize any activities to a higher government level, whether regional or national, then the complexity of governing (which can be measured mathematically) becomes greater. And when you're dealing with millions of people, even a small change in governing policy can have truly enormous consequences at the national level.

The Manchus (people from Manchuria) had invaded and conquered China in 1644, and had a unique, low-complexity method for managing the empire. The army was entirely Manchu, and was used to put down any rebellions. They used ethnic Chinese in all administrative positions, but had a separate secret administrative force consisting entirely of ethnic Manchu for intelligence gathering and extorting additional taxes.

By the year 1800, China under Manchu rule was coming apart at the seams. With population growth, prostitution and slavery were increasing, and there were numerous gangs of unemployed laborers looking for work.

Even worse, centuries of bureaucratic buildup had taken its toll. An

example is the Grand Canal, the canal system that was used to deliver

rice from the south to feed Beijing . A huge bureaucracy had been

built up over centuries to manage it. Engineers would build canal

locks with "built-in obsolescence" that guarantee that they'd need

replacement every few years, guaranteeing huge imperial expenditures

to keep them in repair. The barges themselves were operated by

thousands of bargemen who had their jobs through heredity, but who

hired gangs of workers to do the actual work. China in 1800 was a

poster child for the "crusty old bureaucracy" that we discussed in

chapter 6 (see page [depression#78]).

. A huge bureaucracy had been

built up over centuries to manage it. Engineers would build canal

locks with "built-in obsolescence" that guarantee that they'd need

replacement every few years, guaranteeing huge imperial expenditures

to keep them in repair. The barges themselves were operated by

thousands of bargemen who had their jobs through heredity, but who

hired gangs of workers to do the actual work. China in 1800 was a

poster child for the "crusty old bureaucracy" that we discussed in

chapter 6 (see page [depression#78]).

There have been numerous regional crisis wars and massacres

throughout China's history, as in the rest of the world. Presumably,

most of those were fought over land and resources as usual. Because

these crisis wars were all regional, and happened at different times,

it was possible for the Manchus' ethnic army to suppress each

rebellion in turn, as it occurred, and to maintain control in this

way. In fact, the legacy of Emperor Ch'ien-lung, who ruled for sixty

years until 1799, describes "Ten Great Campaigns" to suppress rebels

on the frontiers . One rebellion, for example, occurred in

Taiwan in 1786-87

. One rebellion, for example, occurred in

Taiwan in 1786-87 . Presumably, the "great compromise" that ended

each of these regional wars and rebellions was that the Manchu army

would leave people alone if they'd stop fighting and just pay their

taxes.

. Presumably, the "great compromise" that ended

each of these regional wars and rebellions was that the Manchu army

would leave people alone if they'd stop fighting and just pay their

taxes.

|

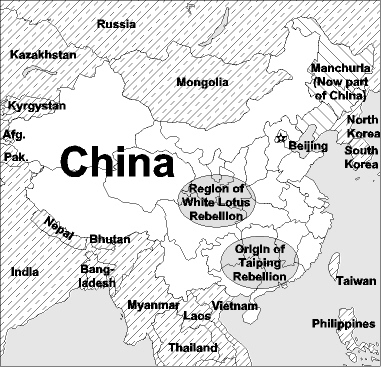

The first rebellion that forced a major compromise in the Manchu

government itself was the White Lotus Rebellion in central China (see

adjoining map). It broke out in 1796, over the issues of poor public

service in return for high taxes .

.

As often happens, the rebel leaders used religion as the face of the rebellion. The White Lotus religious sect was based on Buddhism, and had faced previous attempts by the Manchus to suppress it, presumably because the sect was a menace to social order. The pattern by which the rebellion took place has happened many times before and since and many places in the world: the religious sect appeals to unhappy people by making various promises, the leaders of the sect mobilize them into a military force with political goals, and then the military force either achieves its political goals or it's suppressed.

Although the White Lotus rebellion was a regional rebellion, it played out over a larger region than previous rebellions had done. As a result, the ethnic Manchu army was not enough to contain it.

By 1800, it was pretty clear that the corrupt, bureaucracy-ridden Manchu army would not be able to suppress the rebellion. The Manchus were forced to take an unprecedented step: They employed Chinese militia under Manchu control to quell the rebellion. This proved to be the first major step in the downfall of the Manchus, but just one of many steps to come.

In fact, the White Lotus rebellion was a kind of prototype for what was to come. Within 50 years, a much larger rebellion was to bring about massive violence.

First though, the Opium Wars of 1840-42 are portrayed as a shameful incident in British history, and indeed, they were shameful because of the trade in opium. But as usual, the situation is far more complex, and much of its outcome would have had to occur anyway, even if opium hadn't been involved.

From Britain's point of view, the issue was open and free trade. The Industrial Revolution had made England had become the world's greatest industrial power. Ever since Adam Smith had published Wealth of Nations in 1776, many policy makers believed that free trade was best for everyone, and so forcing free trade on a backward China was a natural extension of the expansionist policies of the day.

It should first be pointed out that China was not entirely isolated

from international commerce in the early 1800s. It's just that all

commerce was controlled as tightly as possible by the national and

regional governing entities , especially by the imposition of

stiff import tariffs. On the export side, tea, silk and porcelain was

getting very popular in Europe, and all this resulted in a fairly

substantial balance of trade deficit, which favored China's rulers.

With the Industrial Revolution proceeding in England, Europe and

America, it was only a matter of time before someone found some

product or products that would be irresistible to the Chinese, and

would reverse the balance of trade deficits.

, especially by the imposition of

stiff import tariffs. On the export side, tea, silk and porcelain was

getting very popular in Europe, and all this resulted in a fairly

substantial balance of trade deficit, which favored China's rulers.

With the Industrial Revolution proceeding in England, Europe and

America, it was only a matter of time before someone found some

product or products that would be irresistible to the Chinese, and

would reverse the balance of trade deficits.

Unfortunately, that product turned out to be the addictive drug opium, which not only became very popular, but also was not subject to import tariffs, since it entered the country via pirates in violation of Chinese laws. Opium was already illegal in England, so it's hard for the English to claim innocence in selling opium to the Chinese. But complicating the issue were the attitude of the Chinese rulers, who treated outsiders as inferiors, and who did not always live up to the terms of previous treaties.

The war was triggered in 1840 when the government confiscated tons of opium and blockaded the ports, not just to opium but also to all outside trade. That was too much for the English, who declared war. The First Opium War lasted until 1842, when Beijing was forced to capitulate and sign a treaty. The treaty forced all ports open to foreign trade and gave Hong Kong to the British. (It was not returned until 1997.)

China's easy defeat was an enormous blow to the Manchu leaders. In the long run, it led to a program of "Self Strengthening" which was implemented throughout the last half of the 1800s. Its purpose was to develop technology, factories and military capabilities to prevent another such defeat.

Returning now to our earlier point, China would eventually have had to open up its trade to outsiders, and would eventually have had to develop its own technology. The fact that these changes increase the complexity of the national government is beside the point. These trends must occur because they always occur. The government regimes must figure out how to deal with these changes, since nothing can stop the changes.

As we use our study of China's history to focus on how the trends that every society goes through, we have to understand that we've been describing two different kinds of trends that go on at the same time in every society:

These two kinds of trends go on at the same time, and they interact with one another. If a crisis war occurs, a historian will search for causes of the war among the growth trends, and he will always find them, because any growth is going to strain a society somewhere, causing some dissatisfaction. The thing to keep in mind is that there are always growth strains going on, but they don't lead to a crisis war except as the result of a generational cycle.

Presumably, the previous regional crisis war in the southeast of China began in the 1760s or so, and was violently suppressed by the Manchu army. By the 1840s, society would have been unraveling: men were becoming addicted to opium in violation of Manchu laws, and opium was pouring in, first because of pirates, and later legally, after the Opium War agreements had been signed. The effect would have been greatest in the southeast, where all the ports were, and where the opium was pouring in. The money to pay for the opium would have created a fiscal crisis, which would only have been exacerbated by a famine that occurred in the southwest in 1846-48.

As usual in China, the rebellion was first voiced through a religious

sect. In this case, the sect was a version of Christianity, created

by taking the teachings of the missionaries, mixing in a little

Buddhism and politics, and coming up with the God-Worshipper's

Society, which appealed to large numbers of disaffected

citizens .

.

The rebellion exploded to the north to Beijing, and then into the heartland of central China. Armies of tens of thousands of men would live off the land, gaining new recruits as it went along.

The rebellion was not put down until 1864, and then not by the Manchu

army but by an army of Chinese recruits. Modern estimates are that

China's population had been about 410 million in 1850 and 350 million

in 1873 -- after the end of the Taiping rebellion and several other

rebellions that occurred in the west .

.

This indicates a loss of about 15% of China's entire population; compare this to the most devastating of America's wars, the Civil war, where we lost less than 1% of the entire population.

The Taiping Rebellion forced some changes on the government structure, but remarkably, the Manchus were left in place, as were most of the centuries old Manchu bureaucracies. The major changes that did occur were in the militias, which were no longer composed just of ethnic Manchus, but became majority Chinese.

The next few decades saw China struggle vehemently to catch up to the rest of the world in technology, finance and trade. The aforementioned "Self Strengthening" was the government program that was to accomplish this, but events crowded the Chinese faster than they could make changes.

Many people view these events in a purely political light: The imperialist Eurocentric Western society imposed its values on the workers of China and took advantage of them repeatedly.

Here's a more politically neutral interpretation:

China and the West were both on the same technology growth curve, but by pure historical happenstance, Europe was about 200 years ahead of China. This could have happened simply because the first humans to populate China came 15,000 years after they populated the Mediterranean basin, and China did not completely catch up by 1800.

Since 1845 and the "Self Strengthening," China has been marshalling its resources to develop the technology to make up for that 200 year difference.

The problem is that with over a billion people, China is almost impossible to govern at all, let alone to govern and transform all at once.

Nonetheless, China is moving as fast as it can, and hopes to catch to the West and be at a technological parity within a few decades.

The Chinese Rebellion of 1911 removed the Manchu control of China for the first time in hundreds of years. Why isn't so major a change counted as a crisis war?

The answer is that the Chinese Rebellion didn't really change Chinese society. While the ruling families at the top changed, the basic structure of Chinese society didn't really change.

It's important to remind ourselves again what the basic premise of this book tells us. The Taiping Rebellion was a horror greater than we can even imagine today, even for those who remember World War II. Tens of millions of people were massacred over an almost 20 year period, and no one who had lived through it would ever want to see anything like it happen again. In 1911, there were still plenty of people around who had lived through the Taiping Rebellion, and there was little energy for the kind of explosion that had occurred only a few decades earlier.

Although there was some fighting associated with the Chinese Rebellion, it probably makes sense to compare it to England's Glorious Revolution, in that a major change of Chinese government occurred with little blood spilled, as a result of a traumatic civil war that occurred only a few decades earlier.

During the 1920s, the Chinese government split into two major factions: A Nationalist faction, led by Chiang Kai-shek, which began to ally itself with Germany, and a Communist faction, led by Mao Zedong (Mao tse Tung), which allied itself with Russia after the latter's Bolshevik Revolution.

The two worked together until 1927, but split openly at that time, with the Nationalist faction taking over and forcing the Communist faction into the countryside.

| Exactly 82 years after the Taiping Rebellion moved north from the southern provinces, Mao Zedong began his Long March from the same region |

The Nationalist government still had not solved the problem of

governing the vast Chinese population, and had developed an

insufficient technique for dealing with the problem. Chiang followed

the example of his German ally by installing a secret police to

closely control the large cities and collect taxes. This might have

been a good strategy in urban Germany, but with China's huge agrarian

population, the army was left to manage the provinces and collect

land taxes. This dual strategy permitted modernization of government

at the highest regional levels, but it allowed for a great deal of

corruption in the countryside, where the army officers became wealthy

landowners . (We won't dwell on this here, but this situation is

similar to the situation faced by Mao in the Great Leap Forward

discussed below; in both case, you can use the mathematics of

Complexity Theory to prove that it's impossible to manage a huge

population in this way.)

. (We won't dwell on this here, but this situation is

similar to the situation faced by Mao in the Great Leap Forward

discussed below; in both case, you can use the mathematics of

Complexity Theory to prove that it's impossible to manage a huge

population in this way.)

At another time, the Nationalists may simply have been able to abolish the Communists completely, but the time of the generational cycle was approaching: the people who had personal memory of the Taiping Rebellion were almost gone. The generational anxiety was exacerbated by a financial development: hard money reserves were being drained, forcing Chiang to abandon the gold standard in 1934.

Exactly 82 years after the Taiping Rebellion moved north from the southern provinces, Mao Zedong began his Long March from the same region. To the Chinese, Communism was not unlike a religious sect; and just as Buddhism and Christianity had both been heavily modified to inspire the White Lotus and Taiping rebellions, respectively, Mao heavily modified Stalin's Communism to adapt to the Chinese ways. Nonetheless, one thing remained: the hostility to wealthy landowners, and to the rents that they collected, and this factor highly motivated the peasants to follow Mao.

Of the 100,000 followers who began the 6,000-mile Long March, only 20,000 or so survived. But along the way, Mao became the unquestioned leader of the Communist movement, and the Communists were established as a credible alternative to the Nationalists.

Undoubtedly a massive civil war would have begun immediately, but for the fact that World War II had already begun for China. The Japanese, who had annexed Korea in 1910, used it as a base to invade and conquer Manchuria (northeastern China) in 1932. In 1937, Japan and China were in full-scale war, with Japan headed for Beijing, and Mao Zedong and Chiang Kai-shek had come to an agreement to cooperate to defeat the Japanese.

All in all, the Japanese invasion proved an advantage for Mao. Chiang was allied with Germany, but Germany withdrew much of its help in deference to its other ally, Japan. Russia's Stalin was not so encumbered, and was fully engaged in seeing another country implement a Communist government.

When Japan surrendered to America in 1945, the civil war broke out for real. By 1949, the Nationalist government had surrendered to the Communists, and Chiang Kai-shek had fled to the island of Taiwan. The continued separation of Taiwan from China remains a fault line to this day, a fault line which may well play a part in the next world war.

Mao was certainly a very charismatic figure who captured the admiration of his country and of the world, but his period as China's leader cannot be considered anything but a disaster.

Millions of people died from execution even in the "good times" of

Mao's leadership, but no period was worse than the Great Leap

Forward, during which some 20 to 30 million people died of

starvation in a man-made famine .

.

It's really very hard to explain what happened in the Great Leap Forward in any rational way. That the Great Leap Forward could never have achieved its goals is obvious today, and perhaps Mao could be forgiven for not knowing that at the time, but he can't be forgiven for putting the lives of some billion peasants at risk without implementing even the elementary management controls and an unwillingness to stop his experiment earlier.

| It's really very hard to explain what happened in the Great Leap Forward in any rational way |

As we describe in Chapter 11 (page [trend#57]), the problems of governing a huge population can be modeled using the mathematics of Complexity Theory. In a nutshell, the problem is this: If you have a small population, say a feudal region of 300 people, then the leader and one or two aides can monitor all the transactions that go on between people: Buying and selling, employee-employer, loaning money, and so forth. But as the population grows, then the number of transactions to be monitored grows much faster than the population, meaning that a greater and greater percentage of the population has the job of monitoring transactions. If this continues, then eventually the whole population would do nothing but monitor each other's transactions, but the system breaks down long before that happens. That's why, as the population gets larger and larger, the only economic system which is mathematically possible is a free market system, where the government monitors almost no transactions, and things like product pricing are determined by competition in the marketplace.

What does this have to do with the Great Leap Forward?

Mao tried to devise a set of ideological rules that would defeat the mathematical realities just described. When it started to become evident, within a few months, that the system was breaking down (which the mathematical theory says must happen), then Mao purposely allowed ideology to override reality, with the resulting tens of millions of death from starvation.

Mao's plan to implement "true" communism in China began in 1958 with

the Great Leap Forward. Here's a summary of how the program worked :

:

Mao's stipulated purpose was to mobilize the entire population to transform China into a socialist powerhouse -- producing both food and industrial goods -- much faster than might otherwise be possible. This would be both a national triumph and an ideological triumph, proving to the world that socialism could triumph over capitalism.

First, Mao dismantled the Central Statistical Bureau, the

organization responsible for keeping track of all the economic

activity going on in the country . As a result, China's

leadership had no real idea whether the Great Leap Forward was meeting

its objectives or not.

. As a result, China's

leadership had no real idea whether the Great Leap Forward was meeting

its objectives or not.

Early in 1959, and again in July 1959, officials in Mao's government had begun to see that the program was failing. Their objections were rewarded with punishment. Mao was determined to follow his ideological course, no matter what else happened.

| Mao dismantled the Central Statistical Bureau, and so had no real idea whether the Great Leap Forward was meeting its objectives or not. |

The program failed because of the complexity of closely governing a large population, as described above.

The individual peasants and managers were required to report the size of the crop harvests up the line to the central government, but there was no way to guarantee that the reports were accurate.

On the one hand, there was no economic incentive for the farmers and managers to provide accurate reports, since everyone in a socialist society is paid the same ("according to his need").

On the other hand, there was no independent check of the crop harvest estimates. If the population had been much smaller, then the central government might have been able to send out enough bureaucrats to check the reports, or at least do spot checks. But with about a billion peasants, no such meaningful checks were possible.

For the farmers and managers themselves, there was plenty of political incentive to overreport the crop harvest results.

As a result, even though actual crop yield in 1959 was a little

smaller than it had been in 1958, the crop reports added up to an

enormous increase in production, more than a doubling of output .

.

By the time that Chairman Mao was finally ready to accept the situation, it was too late. There was too little food to feed everyone, and tens of millions died of starvation.

Chairman Mao was disgraced by the disastrous failure of the Great

Leap Forward, and his critics proliferated . By 1966, Mao had

devised the Great Cultural Revolution to repair the situation, and

formed the Red Guards to implement the assault on dissidents:

. By 1966, Mao had

devised the Great Cultural Revolution to repair the situation, and

formed the Red Guards to implement the assault on dissidents:

; they fought pitched battles, carried out

summary executions, drove thousands to suicide, and forced tens of

thousands into labor camps, usually far from home. Intellectuals were

sent to the countryside to learn the virtues of peasant life.

Countless art and cultural treasures as well as books were destroyed,

and universities were shut down. Insulting posters and other personal

attacks, often motivated by blind revenge, were mounted against

educators, experts in all fields, and other alleged proponents of

"old thought" or "old culture," namely, anything pre-Maoist.

; they fought pitched battles, carried out

summary executions, drove thousands to suicide, and forced tens of

thousands into labor camps, usually far from home. Intellectuals were

sent to the countryside to learn the virtues of peasant life.

Countless art and cultural treasures as well as books were destroyed,

and universities were shut down. Insulting posters and other personal

attacks, often motivated by blind revenge, were mounted against

educators, experts in all fields, and other alleged proponents of

"old thought" or "old culture," namely, anything pre-Maoist.Hundreds of thousands more deaths occurred under the Red Guards.

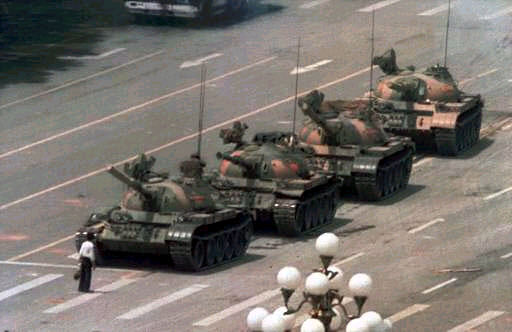

Probably the most dramatic "awakening" event ever televised occurred in 1989, over a million Chinese colleges students from all of the country crowded into Tiananmen Square in Beijing for a peaceful demonstration. Government troops entered Tiananmen Square at night and fired at the sleeping student. In the end, several thousand were killed.

This violent reaction indicates that China has not yet figured out how to govern its population, and that another violent rebellion will envelope the country within the next 20 years.

|

Civilization came rather late to Japan -- after 500 AD. As an

island, it had relatively little contact with outsiders until the

1800s. As a result, the Japanese developed a remarkably homogeneous

appearance and a homogeneous culture -- a sense of conformity,

acceptance of hereditary authority, devotion to the soldier, ideal of

self-discipline, and its sense of nationalism and superiority of the

political unit over the family .

.

In this chapter, we focus on Japan's history since the major crisis that occurred starting in 1853.

This 15-year crisis, culminating in a civil war and the first structural change in government in centuries, was the event that exploded Japan into the rest of the world, and set the stage for Japan's entry into World War II, and its attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941.

The Tokugawa family had been ruling Japan since 1603, after a coup at that time which overthrew the existing rulers. This era is called the "Edo Era" because the Tokugawas were able to unify Japan under rule from the city of Edo, which was renamed Tokyo in 1868.

The pattern in Japan after 1853 was similar to what happened in China after the Opium Wars. Like the Manchus in China, the Tokugawas in Japan had built up an enormous bureaucracy, crusted with inefficiency. To protect this bureaucracy, and to reduce the complexity of governing, they had strictly forbidden trade with other nations. Foreign travel was forbidden, and Christianity was banned.

The crisis began in 1853, when US Commander Matthew Perry brought four warships to Edo (Tokyo). There was a brief naval battle that the Americans won easily. In 1854, Japan signed a treaty with the US that opened up several Japanese ports in a limited way. In the next two years, Japan signed similar treaties with Great Britain, Russia and the Netherlands.

This alone would have caused turmoil by shaking up the bureaucracy, but a disaster occurred: an earthquake that killed thousands of people in Edo.

A series of wars ensued -- mostly civil wars, but also a brief war with England in 1862. By 1868, the Tokugawas were overthrown, and rule by the Emperor was restored. It was called the Meiji Restoration, where the word Meiji means, "governing clearly," hinting at simplicity rather than complexity.

Japan's defeat by America was as much a shock to them as the China's defeat in the Opium Wars was to them. And Japan instituted some reforms like China's "Self Strengthening," whose purpose was to catch up to the world in technology, industry and military capability.

In fact, along with its industrialization initiative, Japan instituted numerous other reforms following the Meiji Restoration, including nine years of compulsory education for everybody. It's possible that this reform is what made the difference between Japan succeeding where China failed.

In this book, we've discussed a wide variety of types of awakenings -- great art in the "golden age of Greece," new religions in the lives of Jesus, Mohammed, and the Buddha, and the anti-war movement in our own awakening of the 1960s.

However, an awakening can take many forms, and Japan's awakening took the form of becoming militaristic and imperialistic. The Japanese were well aware of the successes in empire building by the Europeans, and they felt that if the Europeans could do it, then the Japanese could also do it.

From 1894-1910, Japan engaged in a series of wars against China and Russia, resulting in one victory after another. In the treaties resulting from these wars, Japan was given Taiwan, Korea, and southern Manchuria, along with other territories.

| Writing in 2003, there's a startling parallel between Korea today and Japan in the 1930s |

We should make clear that Japan was not considered to be an enemy of the West at this time. In fact, Japan was considered to be an advanced, "westernized" nation. Japan mostly sat out World War I, but at the Treaty of Versailles ending that war, Japan was granted additional territorial awards.

Never having been an imperialistic nation, Japan was becoming giddy with its successes. An awakening period is followed by an unraveling period, and in the unraveling period of the 1920s, Japan became a completely militaristic state. There was censorship of the press, complete state control by the military, and open plans for military expansion into China and Russia.

The stock market crash in America didn't affect Japan until America enacted the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act (see page [americanhistory#192]), which caused a collapse in international trade, and started Japan's own financial decline. Japan already felt insulted by America's 1924 decision to limit immigration into the US -- citizens of all non-North American nations were restricted, but immigration by Japanese was singled out as being totally excluded.

Exactly 63 years after the Meiji Restoration (78 years after Commander Perry's visit), Japan went to war in Manchuria in 1931. This was the first major military action of World War II.

Japan was then at war until America's nuclear weapons fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945. Japan surrendered on September 2.

Almost overnight, the Japanese people reverted to the old non-imperialistic selves they used to be before Commodore Perry's visit. The country became strongly pacifist and disbanded its armed forces.

However, Japan's change does not dissolve the ethnic fault line between Korea and Japan, resulting from Japan's colonization of Korea from 1910 to 1945. We're likely to see a war of Korean unification during the next few years, and it's likely that Japan will be drawn into that war.

Writing in 2003, there's a startling parallel between Korea today and Japan in the 1930s. North Korea's Kim Jong-il has been making extremely belligerent statements, quite evidently imitating the behavior of the Japanese during the 1930s that led to the bombing of Pearl Harbor, as we described in chapter 2. Because of Japan's colonization of Korea during that time, Koreans still have a vivid memory of that period.

In order to understand what happened in America's Vietnam war in the 1960s and 1970s, it's necessary to go back in time 80-90 years.

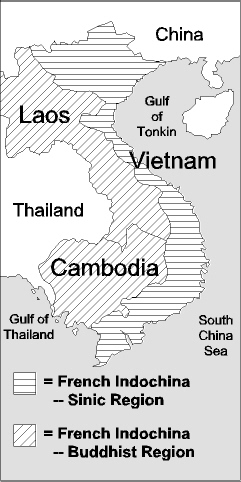

France developed a close relationship with Southeast Asia throughout the 1800s, largely through Catholic missionaries. French activity in the area increased, with France attempting to annex various regions as French protectorates. Full-scale war broke out in 1882, leading to war against China in the region. By 1893, France had consolidated its hold on the entire region known as French Indochina (see adjoining map). France held the region until 1940, when they were forced to relinquish it to a Japanese invasion. French control was reestablished in 1946, but the French were defeated and driven out by Ho Chi Minh in 1954.

America, fresh from defeating Nazism, was determined that "nothing like that must ever happen again." It was (and is) widely believed that if Hitler had only been stopped in 1935, then World War II could have been avoided completely -- a belief that this book claims to refute.

But the fact that it was believed led the Americans to try to prevent the Communist Chinese, operating through Ho Chi Minh, to gain control of the entire country, believing that if Communism could be stopped early, then World War III could be avoided. American entered the war in the 1960s on the side of South Vietnam, to prevent the Chinese to gain control over the whole country.

Between 1965 and 1980, about 80-90 years after the French Indochina wars in the late 1800s, the entire region was in a genocidal civil war.

The Vietnam War was a crisis war for the Vietnamese, but a mid-cycle war for America, which was still exhausted from World War II, and suffered substantial anti-war resistance at home.

|

Starting with the Tet offensive of 1967, the North Vietnamese fought with enormous energy, while the Americans fought half-heartedly. American was defeated by 1974.

Many commentators have offered the view that huge genocide that occurred in Cambodia and Laos in the 1970s was caused by the Vietnam War, but there seems to be no more than the slightest connection.

Many Americans believe that the entire population of Southeast Asia is fairly homogeneous, but in fact, the opposite is true. As can be seen from the map shown above, Vietnam's population belongs to the Sinic (Chinese) civilization, having been infiltrated by the Chinese as early as the second century AD.

But Cambodia and Laos were from an entirely different civilization -- Buddhist cultures that grew out of settlers from India coming through Thailand.

Vietnamese attempts to control Cambodia date back centuries, with a major genocidal war involving Cambodia, Vietnam and Thailand occurring in 1840. According to the 80-year cycle view of history, this war would have recurred in the 1920s, if France hadn't intervened in the late 1880s.

In the 1970s, 80-90 years after the French intervention, both Cambodia and Laos exploded into civil war. In both cases, the civil wars followed the disastrous examples of Mao Zedong in China two decades earlier, with the same results -- massive genocide and starvation.

The line separating Vietnam from Laos and Cambodia is more than just a boundary -- it's a major fault line between two civilizations, one coming out of India and one coming out of China. These countries are "scheduled" to have another crisis war around 2030-40, about 20 years later than China itself is "scheduled" for another massive nationwide rebellion. It's possible that these two crisis periods will coalesce into a single larger crisis period.