Dynamics

|

Generational Dynamics |

| Forecasting America's Destiny ... and the World's | |

| HOME WEB LOG COUNTRY WIKI COMMENT FORUM DOWNLOADS ABOUT | |

|

These pages contain the complete manuscript of the new book

Generational Dynamics: Forecasting America's Destiny,

written by John J. Xenakis.

This text is fully copyrighted. You may copy or print out this

material for your own use, but not for distribution to others.

Comments are invited. Send them to mailto:comments@generationaldynamics.com. |

This book is about the major crises in world history, especially those involving great crisis wars.

But there's a special delight in studying the awakenings -- those spectacular times of new ideas and new revolutions that appear midway between two crisis wars.

Some awakenings produce little, perhaps a few ideas that fizzle out to nothing. Other awakenings produce ideas and movements that change history. Those are the awakenings that excite us and teach us what moves men.

The 80-year cyclical view of history is also a methodology -- that sometimes allows us to fill in the blanks in history, to let us make reasonable inferences about things that happened years ago, and have been lost in history.

In this chapter, we look at some of the most interesting, delightful and important awakenings in world history: The golden age of ancient Greece, the ministry of Jesus Christ, and the life of Mohammed and birth of Islam.

Before beginning, let's remember what an awakening is. The word "awakening" comes from a particular historical event known as the "Great Awakening." It occurred in colonial America in the 1730s-40s. For the first time in history, multiple religious denominations were born, as evangelists moved around the colonies.

Let's summarize two recent awakenings, to make it clear what kinds of things happen during an awakening.

What both of these awakenings have in common -- as do all awakenings -- is a "generation gap" between the youngsters who were born after the last crisis, and their elders, who lived through the last crisis and do not want to see it repeated.

In using Generational Dynamics to analyze this period, the timeline isn't entirely clean, because there are so many parties involved, and they all come to the period with their individual timelines. As a result, the two crisis periods are each 30 years long, and the mid-cycle period is just under 50 years long, and includes several mid-cycle wars. Nonetheless, the awakening that occurred during this mid-cycle period is quite real.

Today, we think of the world consisting of about 250 nations, or "nation-states."

However, no one ever heard of nation-states in fifth-century BC Greece. Nor did ancient Greece consist any longer of mobile warring tribes. Instead, ancient Greece was made up of "city-states," small societies tied down to fixed geographical locations. Each city-state had its own form of government, and many of them were democracies. The two most well known city-states were Athens and Sparta.

|

There were three major parties to the crisis period that began in 510 BC: Athens, Sparta and Persia. All three were historical enemies of each other, but in the beginning of this period, Sparta encouraged the Persians to attack Athens. By the end, Athens and Sparta were allies.

In the final major battle, in 480 BC, Persia had 5 million men,

according to the historian Herodotus, considered the first true

historian of the western world. However, modern estimates range up

to 500,000 men . In addition, Persia had 600-1200 ships. During

the ensuing battles, Persia attacked and occupied Athens, and

destroyed the city.

. In addition, Persia had 600-1200 ships. During

the ensuing battles, Persia attacked and occupied Athens, and

destroyed the city.

At a time like today, when the world may be headed for a major war, it's time to remember that some hostilities last seemingly forever. The Persians lived on what is Turkey today, and today, 2,500 years later, there is still a great deal of hostility between Greece and Turkey, and the island of Cyprus is a major fault line in that war. It's possible that Greece versus Turkey will play a major part in a future war.

As usual, the period immediately following a war is very austere, as steps are taken to make sure that "nothing like this ever happens again." Very often, there's some great compromise imposed on one side or the other that unravels years later.

In this case, the great compromise occurred in 478 BC, when Sparta

proposed to Athens that they form a Delian League (named after the

island Delos) of all the city-states: Each ally would contribute to

the league, which would use the money to drive away all

Persians . The League was supposed to be controlled jointly by

the allies, but Athens was the most powerful, and soon completely

dominated the league.

. The League was supposed to be controlled jointly by

the allies, but Athens was the most powerful, and soon completely

dominated the league.

The kids who were born after the Persian war would have a different point of view. They would see Persia as a distant, weak enemy, and any money saved for a possible future war against Persia to be wasted. Their attitudes would be quite different from those of their parents, the people who had actually fought in the war and seen their friends die. As usual, this created a generation gap.

Beyond that, the kids from Athens would have quite a different view from the kids from Sparta and the other city-states. The kids from Sparta would want to end the Delian League and stop paying taxes to Athens for a defense they wouldn't believe was necessary.

The kids from Athens wouldn't want to end the League, but they would want to see fewer "defense expenditures," and would want to see the money spent instead on program for "social good." These are the typical views heard during awakenings, whether today or in ancient times.

This is a good example of how a compromise that ends a war can lead to the next war between future generations. The young generations of Athens and Sparta both felt "entitled," because their elders had all contributed to the great heroic victory over Persia. But they interpreted their entitlement differently, and in conflicting ways.

| The kids from Athens would have a different view from the kids from Sparta |

The result was that the Delian League turned into an Athenian empire. Athens could exert control over the other city-states because it had control of the vast taxes and resources collected for the common defense. Whenever any city-state tried to withdraw from the League, Athens would use its power and resources to force it to return. At its peak, there were about 140 city-states in the Delian League.

Pericles, the great statesman of Athens at this time, played a major role. He had been born at the beginning of the Persian War, and grew up during it. Kids who grow up during a crisis war have a unique attitude toward life. They personally experience the horror of the crisis war, and want any future wars to be prevented; but they're too young to actually participate in the war, as their older hero brothers did. And when their younger brothers are born, to become the post-war generation, they end up being mediators between these two hardheaded generations.

Pericles rose to power by juggling the demands of both of these generations. For the older generation, he maintained Athens' defenses, and even extended Athens' hegemony to other nearby regions.

For the younger generation, he instituted a modest welfare program for the poor, sponsored artists like Aeschylus, and initiated public works projects that both provided jobs and beautified the city.

In the period between two crisis wars, an "unraveling" typically occurs in the last couple of decades before the next crisis war in the cycle. At this time, mediators like Pericles are no longer caught between two hardheaded generations, because the older generation of heroes has retired or died. They're at the height of their power and influence, but they're only being pushed in one direction.

Under Pericles' influence, Athens commissioned the Parthenon and other buildings of the Acropolis, some of the greatest and most beautiful buildings of all time. The reason given was to replace the buildings that had been leveled by the Persians during the war. But nothing was too good for the Acropolis. The Persians had leveled buildings constructed with porous stone, available near Athens, but the buildings of the Acropolis were constructed from the finest hard white marble, quarried from miles away.

This was great fun for the Athenians, but not much fun for the other city-states, since the others were footing the bill for Athens' beautiful buildings. The result was the next crisis war: the Peloponnesian war between Athens and Sparta that started in 431 BC, 59 years after the beginning of the Persian War. That civil lasted 27 years, leaving the entire region exhausted and weak.

The weakened Greeks were unable to withstand the next major war. King Philip, king of Macedonia and father of Alexander the Great, invaded and conquered the Greeks in 359 BC, and uniting all the Greek city-states as part of the Macedonian empire. But that's not all.

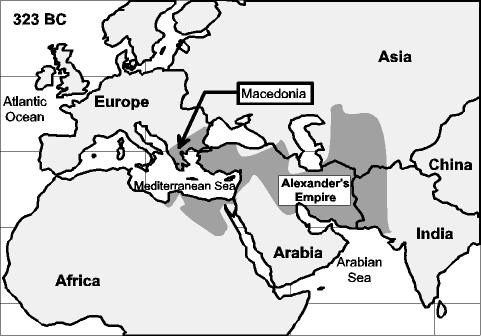

King Philip's son, Alexander the Great, formed an army of Macedonians and the conquered Greeks, and went on to capture Egypt, the Persian Empire, and parts of India and central Asia, as shown in the accompanying map.

In doing so, Alexander the Great spread Greek culture, including the Greek language and the accomplishments of the golden age of Greek culture, throughout the entire region. Three centuries later, when Jesus Christ was born and Christianity was founded, the New Testament of the Bible was written in Greek, the lingua franca of most of the known world.

|

At this point, it's appropriate to ask: What has this analysis of the Golden Age given us that we didn't already know? For example, the fact that Athens used Sparta's tax money to build the Parthenon, and that this triggered a new war between the parties, has already been well established by historians. So why bother?

What the generational methodology adds is a lot of context and relevance to the bare facts. We can understand that the Delian League was supported immediately after the Persian War for the same reasons that our own FBI and CIA were supported. We can understand how the existence of Delian League was questioned by activists very similar to our own anti-war activists in the 1960s and 70s. We can see that the Parthenon was built at a time of craziness or unraveling, like our own 1990s, when there are no social rules and no financial controls.

Finally, as we look at example after example, and see the same patterns repeated over and over again, we can really begin to understand our own futures -- how in 2003 America is at a point just before a major crisis war, how the war will last ten years, more or less, how it will lead to a great period of austerity, followed once again by a generation gap will lead to new challenges to authority in the 2030s.

Great ideas are born during awakenings, and frequently they're spread (or extinguished) during crisis wars. Now we're going to look at another great idea, born during an awakening, and spread throughout the world for millennia to come -- the ministry of Jesus Christ and the spread of Christianity.

It's impossible to understand Jesus Christ without first understanding the history of Judaism, as well as the unique qualities of Jews that have caused them to excel at whatever they did -- the same qualities that have led them to be the targets of attack by other civilizations throughout the centuries.

The seminal crisis war that set the pattern for Hebrew life for millennia to come occurred somewhere around 1200 BC (give or take a century), when Moses liberated the Hebrew people from Egyptian slavery by means of two miracles: the crossing of the Red Sea and survival in the desert. That legendary story, told in the book of Exodus in the Bible, has influenced major world events ever since, to an extent that must not be underestimated. If that event hadn't occurred, the Hebrews might have been just another cult that eventually disappeared, and Jerusalem might have been just another ordinary city, rather than a location that has been the epicenter of one major historical event after another.

Just as the heroic victory of Athens over the Persians started a chain of events that spread Greek culture throughout the world, the heroic victory of Moses and his people over the Egyptians started a chain of events that sustained Jews and Judaism to this day.

For, in the eyes of the Hebrews, this event made them the "chosen people." The two miracles caused them to renew their covenant with God that Abraham had made several centuries, and confirmed their faith that God would protect them.

| The seminal crisis that set the pattern for Hebrew life for millennia was the crossing of the Red Sea |

In the austere days following the exodus, Moses took steps to make

sure that "nothing like that must ever happen again." He imposed the

Ten Commandments on the people, and then developed an entire moral

and religious code, a code of political and social organization .

The covenant with God, made centuries earlier by Abraham, presumably

during an awakening period, was now confirmed and established by a

crisis war.

.

The covenant with God, made centuries earlier by Abraham, presumably

during an awakening period, was now confirmed and established by a

crisis war.

This time, the awakening that followed went in a different direction, to the worshippers of the Golden Calf. There must have been many struggles and crisis wars in the centuries that followed, creating a historical fault line between the followers of Moses' law and the others - the heathens.

The view of Jews as the "chosen people" was sealed several centuries

later when the Jews were conquered, exiled into Babylon, and

eventually allowed to return to their homeland. This was once again

interpreted through Jewish law: God had punished the chosen people for

their heathen practices, but then had shown mercy by ending their

exile .

.

The point of all of this history is the set of ideas surrounding the word "Diaspora." This word was originally coined to describe groups of Jewish people scattered around many countries, but now the word "diaspora," without capitalizing, is used to describe any group of people of common religion or ethnicity who are living in a community not in the native country of their religion or ethnicity.

But while diaspora is a general word, it's the Jewish Diaspora that have influenced world events the most. Why is that? Mainly because Judaism has not had a homeland for the overwhelming portion of its history, and so it's always been mainly a Diaspora religion.

No religion could possibly survive without a base, a homeland, and certainly not a religion whose adherents have been exiled, moved or slaughtered so many times in history. Yet, Judaism has survived.

It survived because the Jewish law, starting with the laws of Moses, was designed so that God's chosen people could survive as Diaspora.

As a "chosen people," the Jews could live in any country and still maintain their Jewish identity. Whether in Jerusalem, Egypt, Italy or later in other countries throughout the world, the Jews had a collection of scriptures and laws to live by, and they could reestablish their identity simply by gathering together in a group of two or more and reading and discussing those scriptures. This ability of Jewish Diaspora to live anywhere, anytime, and still maintain a Jewish identity, without merging into the local society, makes the Jews almost unique among major civilizations of world history.

And that's the uniqueness that creates the irrational xenophobia among other people toward the Jews. Jewish people had their own laws that took precedence of the laws of the society around them. (They viewed their laws as coming from a "higher power," a concept that the Christians later inherited, as did the Muslims even later.) Even in earliest times, Jewish communities were insulated, and even had their own courts of law. Some societies tolerated Jewish disobedience of local laws better than others, and the ones that didn't tolerate it often responded by moving the local Jewish community elsewhere, passing the problem on to someone else. This common solution to the local "Jewish problem" meant that Jewish history has almost always been of Jews in other countries, rather than of Jews in their own country.

| As a Chosen People, the Jews could live in any country and still maintain their Jewish identity |

Historian Henri Daniel-Rops puts it as follows:

: everything, their monotheistic faith, love of their

country, submission to moral laws, desire to order their social and

political lives according to given principles, and their feeling for

the highest kind of mystical experience. It was, therefore, theology

rather than ethnology that determined their racial characteristics.

: everything, their monotheistic faith, love of their

country, submission to moral laws, desire to order their social and

political lives according to given principles, and their feeling for

the highest kind of mystical experience. It was, therefore, theology

rather than ethnology that determined their racial characteristics.It's important to understand that most of this description -- a monotheistic faith and submission to moral laws -- is common to Christianity and Islam (and, in fact, was inherited by them). The distinctive difference is the form those laws took resulting from the fact that there was no Jewish homeland.

Following the Golden Age of Greece, Alexander the Great had spread Greek culture and Greek language throughout the Mediterranean area, and into points further east. Whether in Jerusalem or elsewhere in the region, the ordinary people spoke the local language, but the educated elite spoke Greek, enjoyed Greek art, and lived in expensive homes with a Greek architecture. To use modern day terminology, "Hellenization" was associated with the rich, making it a resented symbol of the class struggle between the rich and the poor.

However, the Greeks were not the rulers of this Greek-based culture. These were the days of the Roman Empire, and the Romans were the rulers. The Roman rulers had to deal with large Jewish populations of Jewish Diaspora in Babylon and Rome, and mostly got along well with them (with some painful exceptions) because they granted Jews the right to violate Roman law when it conflicted with traditional Jewish law.

Nonetheless, Judea, the region containing Jerusalem, was a special problem. The Jews actually took control of Judea in 142 BC, and it became a Jewish homeland, an independent Jewish state. In 63 BC, the Romans took over, and there was no Jewish homeland again in 1948.

In 42 BC, Rome appointed Herod to rule Judea. It's hard to imagine any ruler with the ability to cause more dissension and despair among the people. Consider these factors:

Added to all that, there was a natural disaster. In 31 BC, an earthquake killed 30,000 people and leveled thousands of buildings.

Herod ended his reign with especially cruel forms of terror. When some students tried to remove the golden Roman eagle from the temple, some 40 students were burned alive. And the Matthew 2 tells a (possibly exaggerated) story of the "Massacre of the Innocents": When Herod learned of a ruler that the real "King of the Jews" had been born, he ordered the murder of all babies younger than 2 years. Christ was born in 6 BC, and Herod died in 4 BC. The kingdom was divided among three of his sons.

The long reign of terror ended with Herod's death. A crisis period is always followed by a period of austerity, where people who lived through the crisis set rules for society so that nothing like that will ever happen again. For the Jews, this meant that they would not provoke the Romans, and for the Romans, this meant that any minor revolt had to be put down quickly, in order to avoid a larger revolt. There was an extended period of peace between 7 and 26 AD.

Jesus Christ was born too late to have any personal memory of Herod's reign of terror. There's always a "generation gap" between the generation of children born after a crisis period and the people who lived through the crisis period. That's why so may great new ideas, like a new religion, almost always occur 20-40 years after a crisis period ends -- that's when there's a new awakening.

As a member of that young rebellious generation, we can well imagine that Jesus Christ would have wanted to rebel against not only the Romans but also against the elders in his own community, people who would be telling him to keep quiet, lest he cause trouble for himself and themselves.

Although this is a secular presentation of Jesus' life using Generational Dynamics, it may seem strange, especially to Christians, to be talking about these kinds of generational issues with regard to Jesus, but doing so is no disrespect to the Christian religion, according to Professor Gene Chase of Messiah College in Grantham, Penn.

"Of course Jesus was a man of His time," says Chase. "The very essence of the doctrine of His incarnation is that He is fully man, not just physically but also socially, intellectually, and emotionally. Jesus was a man of his culture, and hence a man of the culture of his time. He studied the Torah as a boy; He enjoyed parties as a young man; His parables are agrarian to connect with the culture of His time; He taught peripatetically. These are the sorts of things that one would have expected of a good Jewish boy who became a rabbi. In fact, the Bible even says explicitly that Jesus came at just the right time."

So, for Christian and non-Christian readers alike, there is nothing unreasonable to say that his rebellion got many people angry. He got the Romans angry because of his popularity. He got many of the Jews angry because of his attitude toward the Jewish laws. (According to Matthew 5:17-20, he said, "Do not think I have come to set aside the Law and the prophets; I have not come to set them aside, but to bring them to perfection." So he "perfected" the laws by ignoring the unnecessary parts, including the dietary laws which were considered extremely important.) So he was a very charismatic rabble-rouser, and he was considered "dangerous" by both the Romans and the Jews.

Why didn't Jesus flee? This is a question that demands an answer from both a secular and a Christian point of view. Jesus knew that the Romans were coming to arrest him and execute him. Why didn't he flee the region (as Mohammed did in a similar situation six centuries later)?

The answer, according to Chase, is that Jesus saw himself as the Messiah as described in Isaiah 53:7, which was written 600 years before Jesus: "He was oppressed and afflicted, yet he did not open his mouth; he was led like a lamb to the slaughter, and as a sheep before her shearers is silent, so he did not open his mouth."

According to Chase, "Jesus saw himself as the person described there, not as molded by his time. Jesus knew Isaiah's writings well and lived in the light of them."

So Jesus was executed / crucified.

During the next 30 years, there were many uprisings among the Jews, resulting in many skirmishes with the Romans. Such skirmishes are typical of the years immediately preceding the next crisis. The hostilities end quickly because, as we've seen, the opinion makers are people who lived through the last crisis, and happily resort to containment and compromise.

By 66 AD, the generation that had personal memory of Herod's reign of terror were gone, replaced as leaders by the post-Herod generation, and the most conservative Jewish extremists had taken over the temple. The entire region was in rebellion against Romans, and the Romans had to "solve the problem once and for all." The Romans massacred tens of thousands of Jews. The city of Jerusalem was destroyed, especially the Herod's new Temple.

This was the end of the Jews in Jerusalem for centuries, but it was the beginning of the spread of Christianity.

How does one convert to a new religion? It depends on the religion, of course.

We're getting a little ahead of ourselves by discussing religions we haven't come to yet, but let's look at how you convert to various religions:

Of these religions, Judaism and Hinduism are "hard" to convert to, while Christianity, Islam and Buddhism are "easy" to convert to.

When I write the last paragraph, I mean no disrespect to any religion. Any Christian, Muslim or Buddhist will tell you that you haven't really converted to that religion just by reciting a few words; you have to study and accept an entire way of life. Nonetheless, you can convert to these religions in a matter of a few minutes, just by reciting a few words or performing a simple rite.

Consider the following: There are Catholic missionaries in China whose purpose is to convert people to the Catholic religion, but there are no Jewish missionaries in China to convert people to the Jewish religion. What's the difference?

The Jewish concept of a "chosen people" is contrary to the idea of proselytizing. That's not to say that proselytizing has never occurred, especially in the old days, but no one would ever expect Judaism to become a universal religion. No one would expect a Chinese Buddhist to convert to Judaism except in very unusual circumstances.

Christianity is the universal version of Judaism. (Incidentally, Buddhism is the universal form of Hinduism.) Any person can become a Christian by becoming baptized. That's why Christianity could spread while Judaism couldn't. And that's why, eventually, someone would have to come along and provide a universal version of Judaism, if Jesus Christ and his followers hadn't done so.

Just as there's no Jewish missionary in China doing proselytizing, you're not too likely to see a Greek Orthodox missionary in China to convert Chinese to the Greek Orthodox religion, or a Russian Orthodox missionary converting Chinese to the Russian Orthodox religion. Once again, what's the difference?

The religion that grew out of Jesus' ministry became the Orthodox religion. It was adopted by the Romans, and then moved east, became centered in Constantinople (Istanbul), and later spread northward to the Slav peoples. Today, the two main branches are Greek Orthodox and Russian Orthodox, although there are dozens of other minor branches.

Orthodox Christianity differs from Catholic (and Protestant) Christianity because the former is a "top-down" religion, adopted first by rulers and then spread to the people, while the latter is a "bottom-up" religion, spreading among the people, and then adopted by the state during fault line wars.

The Orthodox religion moved east to Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey) because Rome was being attacked and pillaged from the west and north, especially by the Teutonic tribes from the North. The Teutonic (German) tribes adopted Christianity, but not in the Orthodox form. Instead a new form, Catholicism, was born. This was a "bottom-up" religion because, as we said, any individual could become a Catholic by being baptized. The same was true of the Protestant religions that split off from the Catholic religions in the 1500s in Germany (then known as the Holy Roman Empire, even though, to use the words of Voltaire, it wasn't holy, it wasn't Roman, and it wasn't an empire).

These are some of the many reasons why Orthodox Christianity is different from Western Christianity.

Let's now do a similar generational analysis on the life of Mohammed, the founder of Islam, and compare his life to Jesus'.

In the case of Jesus' life, there were contemporary Roman and Jewish historians who chronicled the reign of Herod and its aftermath, so that the Biblical accounts are supplemented by a lot of third party information about the environment in which Jesus was born and raised.

By contrast, there is relatively little third party information on

the environment in which Mohammed was born and raised. Almost

everything we know about Mohammed comes from religious sources. In

fact, there are three sources of information about Mohammed's

life :

:

Except for Mohammed's religious teachings that were written down

during his lifetime, most of these sources were not in written form

prior to Mohammed's death, so much of what we know about Mohammed's

life depends on the memories of the writers. A good summary of all of

these sources is Sir John Glubb's book , The Life and Times of

Muhammad.

, The Life and Times of

Muhammad.

Let's start with what we do know about Mohammed.

He was born around 570 AD in Mecca, and became an orphan during his childhood.

None of the writings seems to indicate exactly how his father and

mother died, or whether the death of his parents should be blamed on

any particular tribes or events; we're simply told that his father

died while on a business trip to Medina. We're also told that there

were violent wars, beginning in the 580s, involving Jews, Christians

and pagans, going on around Mohammed while he was growing up, and

that as a teen, Mohammed helped out with some of the battles .

.

| Both Jesus and Mohammed spread their ideas and gained their adherents during an awakening period, midway between two crisis wars |

Around his fortieth birthday, while he was wandering and meditating,

he had an experience that he and his believers say was a visit from

an angel of God, telling him to become the messenger of God . The

angel told him to recite certain verses that he would receive from

God regularly. These verses were eventually collected and organized

into Islam's holy book, The Quran.

. The

angel told him to recite certain verses that he would receive from

God regularly. These verses were eventually collected and organized

into Islam's holy book, The Quran.

His wife, Khadija, and her family were his first supporters, and in time a small group of believers from Mecca began to gather around him. However, his converts included another group as well: traders from the city of Medina (named Yathrib at that time) who visited Mecca regularly. He developed close relationships with these traders, and got to know many of them personally.

Mohammed's life took a dramatic turn in 622, at age 52, when he

became so popular that Mecca's ruling Quraish tribe was threatening

his life . As a result, he and his followers were forced to flee

to Medina, about 200 miles from Mecca.

. As a result, he and his followers were forced to flee

to Medina, about 200 miles from Mecca.

This is a major difference in the lives of Jesus and Mohammed.

Both Jesus and Mohammed spread their ideas and gained their adherents during an awakening period, midway between two crisis wars. Both of them became extremely popular, enough so that the local authorities became concerned about fomenting a rebellion, and threatened each of their lives.

Today, many critics of Islam claim that Mohammed was a "man of war," while Jesus was a "man of peace." Is that a fair criticism of Mohammed?

From a generational point of view, Mohammed was more inclined to be a warrior, simply because he was in the generation that fought in the preceding crisis war, a generation of people that are typically identified as heroes. This distinguishes him from Jesus, who was born after the last crisis war. Some scholars question whether Jesus was totally a man of peace, pointing to the fact that the Bible indicates that Jesus' disciples carried swords.

However, the most dramatic difference between Jesus and Mohammed is how they reacted to these death threats from local authorities. Mohammed's reaction was to flee to Medina, and from there to build an army of adherents. In the case of Jesus, he felt constrained by the writings of Isaiah, as we've already described; in addition, the local authorities were the Romans, who controlled the entire region, so Jesus may have had no opportunity to take his adherents and flee. If things had been different and Jesus had fled, perhaps he might have ended up leading an army of his adherents back to Jerusalem, as Mohammed did to Mecca, but we'll never know the answer to that question.

So there's no way to compare Jesus and Mohammed as warriors, since Jesus never had the opportunity to become a warrior, as Mohammed had.

So, probably a more relevant question is: What kind of warrior was Mohammed?

Both Westerners and Islamic fundamentalists make statements about Mohammed and Islam that frequently aren't justified by the Quran. Let's take a look at the life that Mohammed led in Medina.

It's most important to understand that war was a way of life in the Arabian Desert at the time of Mohammed -- and continued to be so until the early 20th century. The Bedouin tribes regarded perpetual war to be a desirable, or at least inevitable, result of human existence. The Quraish, by contrast, were merchants who considered war to be inimical to commerce.

Some of population lived in fixed homes in one place, such as Mecca or Medina. Others, like the nomadic Bedouin tribes, were constantly on the move. The danger of starvation -- for oneself or for one's animals -- was never far from people's minds.

The tribes formed alliances for mutual protection. Moving

around the desert meant moving from oasis to oasis, and if two

unallied tribes ran into each other on the desert, it's quite

possible that one of them would raid the other. However, such a raid

would not necessarily be a fight to the death, and indeed there was no

honor in simply killing your enemies; the purpose of the fight was to

gain resources, such as food, water, gold, silver and weapons .

.

This way of life was not some sort of peculiar cultural phenomenon, dictated by any of the local religions (Judaism, Christianity, paganism), but rather an adaptation to the desert. The desert produced only enough food and water to support a certain population, and after thousands of years, the local tribes had adapted by developing a pattern of life that selected who will live and who will die -- either from battle or from starvation.

Medina itself was not what we think of as a bustling city; actually, it was little more than a large oasis in the desert supporting several thousand people in settlements of a mix of populations -- Arabs and outsiders of the various religions, including Jews, Christians and pagans.

So this is the way of life of the entire region as Mohammed and his

followers fled to Medina. In Medina, Mohammed actually had two

different roles: His religious role was as the leader of the Muslims,

but he also had a secular administrative role as the leader of the

multi-cultural city of Medina. Many people, especially those who had

followed him from Mecca and had no homes in Medina, were facing

starvation. Mohammed was soon leading raids by Muslims against Quraish

caravans .

.

Mohammed's actions as a warrior were not out unusual for most of the people at this time.

Far from being a violent, genocidal killer, and some people say, Mohammed is more accurately described as an indecisive warrior and killer.

He was frequently uncertain what to do. Should we attack that

caravan or not? He would equivocate, vacillate, sometimes changing

his mind or giving in to pure emotion , often postponing a final

decision until he had absolutely no choice.

, often postponing a final

decision until he had absolutely no choice.

Mohammed was of an older and wiser generation than his young

followers, and he often had trouble restraining them -- not

surprising, since these men were born after the last crisis war. Many

of his young followers were sons of the Quraish elders , and

following Mohammed was an act of rebellion against their parents.

, and

following Mohammed was an act of rebellion against their parents.

Indeed, Mohammed's experience, and the rapid growth of Islam, is almost a textbook example of an awakening in the generational methodology. Awakening wars are rarely especially bloody or genocidal, since the elders on both sides are unwilling to replay the genocides of the last crisis war.

Both Mohammed and the Quraish elders in Mecca that he was fighting against would have been the heroes who had fought and survived the last violent crisis war, and their passionate desire was to avoid another such war. Their children, born after the war, would have found adherence to Mohammed's new faith an appealing way to rebel against their parents. The resulting "generation gap" fueled the emotional fires that allowed Mohammed to return to Mecca as ruler.

Today, in the highly politicized atmosphere following the 9/11 attacks, many Westerners have been making exotic charges about Islam in general and Mohammed in particular.

As we've discussed, Mohammed was a person of his times, not given to unnecessary killing.

Still, the histories and traditions do report some occasions when Mohammed used excessive violence. These are sometimes hard to explain, given the fact that most often he spared the lives of his enemies, or used diplomacy rather than war to achieve a goal.

On those occasions, Mohammed was most violent with people who

attempted to prevent him from establishing his new religion .

Thus, people who actively opposed him would almost always be killed

or massacred. He was also merciless with people who defamed Islam,

either by becoming hypocrites (false converts who pretended to convert

without really doing so) or even just by mocking him or his religion.

An example of the latter was two singing girls who were executed

because their act satirized Islam.

.

Thus, people who actively opposed him would almost always be killed

or massacred. He was also merciless with people who defamed Islam,

either by becoming hypocrites (false converts who pretended to convert

without really doing so) or even just by mocking him or his religion.

An example of the latter was two singing girls who were executed

because their act satirized Islam.

According to the histories, on some occasions, he massacred Jews or Christians, and this has been used by non-Muslims to criticize Mohammed, and by Islamic fundamentalists to justify murder of Jews, even though the histories indicate that such massacres occurred for these other reasons, not because the people were Jews or Christians.

However, these stories of excessive violence by Mohammed should be discounted as untrue, according to Edip Yuksel, an Islamic scholar who promotes reformation in Islam.

"The Quran says that you cannot force people, even hypocrites, to change their beliefs," says Yuksel. "The Quran treats hypocrites worse than nonbelievers, because they have no moral basis for their actions. But there's nothing specified as a punishment. That book says that you cannot hurt people, so Mohammed could not have sent people to hurt people who were hypocrites."

Yuksel says that the stories of excessive violence should not be believed, since they're not in the Quran. "Those stories come from other sources, and there are big lies in those books," he asserts. "Islamic histories written centuries later by other historians created a portrait of Mohammed according to what was going on at the time the histories were written."

According to Yuksel, "Mohammed stood for his rights and for his

freedom - for his beliefs, and he defended himself very powerfully.

But I disagree with anyone who says that he killed people because

they criticized him or his faith ."

."

| Arabs and Jews got along fine for the most part in Jerusalem and the surrounding region until the 20th century |

With regard to Mohammed's attitudes towards the Jews, he had what

would appear to be a love-hate relationship with Jews. At first,

Mohammed had hoped to be accepted by the Jews, and even to be

recognized as the Savior . He adopted the Jewish rules and rites,

and declared Jerusalem to be the holy city toward which prayer should

be made. However, many of the Jews in Medina ridiculed him and opposed

him, and became his enemy. After that, he changed some of his

religious rules and rites so that they differed from those of the

Jews. Furthermore, Mecca, rather than Jerusalem, became the holy city

toward which prayer should be made.

. He adopted the Jewish rules and rites,

and declared Jerusalem to be the holy city toward which prayer should

be made. However, many of the Jews in Medina ridiculed him and opposed

him, and became his enemy. After that, he changed some of his

religious rules and rites so that they differed from those of the

Jews. Furthermore, Mecca, rather than Jerusalem, became the holy city

toward which prayer should be made.

Actually, Mohammed held Jews and Christians in higher esteem than those who followed pagan beliefs. Although he insisted that pagans be converted to Islam, he didn't make that requirement for Jews and Christians, and endeavored to live in peace with them.

Even more important, in the wars of conquest following the death of

Mohammed, Jews and Christians were not required to convert to

Islam . Muslim conquerors exercised enormous religious tolerance

toward Jews and Christians, even to letting them follow their own

laws and customs in conquered lands.

. Muslim conquerors exercised enormous religious tolerance

toward Jews and Christians, even to letting them follow their own

laws and customs in conquered lands.

This is a very important point in today's political climate, because it shows that Islamic fundamentalists are simply lying when they say that Mohammed called for the extermination of Jews and Christians. Quite the opposite, Mohammed tolerated them and even honored them.

As we've already discussed, Arabs and Jews got along fine for the most part in Jerusalem and the surrounding region until the 20th century. After World War I, Jews and Arabs formed nationalist-type identity groups that opposed each other. The real crisis began in the 1930s, when hundreds of thousands of European Jews began fleeing to Jerusalem because of persecution by Germans. Wars between the Jews and Arabs in Palestine began in 1936, and reached a climax in 1948-49, after the creation of the Israel. This has led to the situation in the Mideast today, with the Palestinian Arabs and Jews replaying the events of 1936-49, with a new, major war almost certain.

However, it's important to make the point that this situation is not caused by any reasonable reading of Mohammed's life or the history of Islam. Most wars are fought simply for money, and resources, and then rationalized later with great, noble ideas. What they Jews and Arabs are fighting over today is land and resources, not any great religious beliefs. In the end, it's only about money, and all the stuff about religion is mostly bloviation and rationalization.

Finally, although this point is not directly related to the current Mideast situation, we hear about it so much that it's worth discussing: The charge that Mohammed was indecent because he had many wives, and that a Muslim man is permitted to have several wives.

In today's politically correct society, it's easy to forget that polygamy serves a valuable social purpose at times in history when war had killed off many men, leaving many women without partners. In those situations, the only way for most women to receive protection is through polygamous marriages.

This is exactly the situation that obtained in the Arabian peninsula

for centuries, where war was a way of life. Many of Mohammed's wives

were widows , and there is evidence that many of the marriages

were specifically for the protection of the women.

, and there is evidence that many of the marriages

were specifically for the protection of the women.

During his ten years in Medina, Mohammed continued to gain adherents. He gained the loyalties of many tribes, and built up his army.

Finally, in 630, he led his army back to conquer the Quraish in Mecca. The Quraish, seeing that they would lose, simply accepted Mohammed as the new ruler, allowing his return to Mecca in triumph.

There's no doubt that Mohammed achieved this victory through his remarkable skill as a diplomat and politician, as well as his military skills.

But it's also worthwhile to point out that this was a mid-cycle war. Mohammed did not want to see a repeat of the bloodbath he had lived through as a teen and young adult, and neither did the elder Quraish.

The next bloodbath was saved for the next crisis war, a civil war in

656 among three community groups who were competing to inherit the

mantle of Mohammed's leadership . This serves to illustrate the

point that Muslims have killed other Muslims far more than they've

killed others.

. This serves to illustrate the

point that Muslims have killed other Muslims far more than they've

killed others.

After that, thanks to the aggressiveness of Mohammed's followers, Islam spread like wildfire throughout northern Africa, into parts of Eastern and Western Europe, and farther West into India.

The spread of Islam will be discussed more fully in chapter 9.

Even less is known about the life of the Buddha, the founder of Buddhism, than about Mohammed, and what little we do know of his words and actions has been enhanced by legend. But by using Generational Dynamics techniques, we can try to make some inferences.

Buddhism was born out of Hinduism, the ancient religion of India. The basic culture of Hinduism evolved over millennia, and to Westerners, the most remarkable feature of Hindu culture is the caste system.

It began around 2000-1500 BC, when the existing Indian population

assimilated the Indo-European invaders. The invaders created the

caste system as a means of enforcing racial purity, separating the

conquerors from the conquered . The priestly "Brahmins" were the

highest caste. Other castes were for the warrior-aristocracy, the

ordinary peasant-farmers, and the conquered "unclean."

. The priestly "Brahmins" were the

highest caste. Other castes were for the warrior-aristocracy, the

ordinary peasant-farmers, and the conquered "unclean."

Into this milieu, the Buddha was born around 563 BC into the wealthy warrior caste. His story is a fascinating one, because of its remarkable similarity to a 1960s peace activist. I mean no disrespect but in fact admiration, when I say that the Buddha's story resembles what we Americans might call a well-to-do youth who turned into a disillusioned hippie.

The Buddha became disenchanted with his life of luxury. "I lived in refinement, utmost refinement, total refinement. My father even had lotus ponds made in our palace: one where red-lotuses bloomed, one where white lotuses bloomed, one where blue lotuses bloomed, all for my sake." At age 29, he left his life of luxury and became homeless. His father was appalled. "You are young, ... endowed with the stature and coloring of a noble-warrior. You would look glorious in the vanguard of an army, arrayed with an elephant squadron. I offer you wealth; enjoy it."

He lived a very austere life, fighting temptations and evil. Eventually he reconciled with his father, and found a "Middle Way" of living, between luxury and austerity. During this period, he developed this philosophy of enlightenment, until he had his Awakening. (Fortuitously, the word "Awakening" is used in translations of the Sanskrit text, and corresponds in this case to the word "awakening" used in this book.)

After his Awakening, he spent the rest of long life teaching, and had thousands of followers. His teaching targeted the caste system, because he showed how everyone, even the untouchables and outcasts, could achieve enlightenment. He died in 483 BC at age 80, still teaching on his deathbed.

What additional information about the Buddha can we infer from his life using Generational Dynamics tools? Not a great deal, but a little.

Unlike Mohammed, who evidently spent a portion of his earliest childhood in a crisis war where he lost both his parents, both Jesus and the Buddha were born after the end of a crisis war. But unlike Jesus, whose family was on the "losing side" of the crisis war, the Buddha's family was evidently on the "winning side."

The Buddha's warrior father would have fought in that war. He might have come close to losing his own life, would have seen many of his friends die in battle, and might even have participated in what today we'd call genocide of groups of outcasts. When the rebellion was put down, he and his contemporaries would have renewed strict controls on the activities of people in the lower castes to keep them from rebelling again and endangering his life, as well as their own lives.

The Buddha himself would have been a participant in an "awakening" -- not only his own spiritual Awakening, but also a societal awakening which began to remove some of those restrictions on the lower castes. Eventually, many of the controls and compromises implemented by his father would have unraveled, and there would be a new crisis war or rebellion.

One thing that seems to be missing from the story of the Buddha is another crisis war towards the end of his 80-year lifetime. There are several possibilities. One is that the next crisis war was delayed for some reason, as sometimes happens (see our discussion of the American Revolutionary War, for example). A second possibility is that he didn't want to talk about a new rebellion, since he had personally overseen the unraveling of controls that made that rebellion possible. And a third possibility is that the Buddha's death was the generational change that led to the next rebellion.

A lot of this is speculative, of course, but it provides some interesting inferences that historians can test with further research.