Dynamics

|

Generational Dynamics |

| Forecasting America's Destiny ... and the World's | |

| HOME WEB LOG COUNTRY WIKI COMMENT FORUM DOWNLOADS ABOUT | |

|

These pages contain the complete manuscript of the new book

Generational Dynamics: Forecasting America's Destiny,

written by John J. Xenakis.

This text is fully copyrighted. You may copy or print out this

material for your own use, but not for distribution to others.

Comments are invited. Send them to mailto:comments@generationaldynamics.com. |

As we explained in Chapter 1, the difference between crisis wars and mid-cycle wars is that in a crisis war the population feels a great deal of visceral fear and anxiety that their nation is at stake, or at least that their entire way of life is at stake.

That's why Generational Dynamics does not analyze the actions of any particular leader or any group of politicians; rather, it analyzes and forecasts the actions of large masses of people. For these forecasts to be effective, these people must share a common cultural memory. This means that these analyses and forecasts can only be done for groups of people on a local basis. This leads to what we call the Principle of Localization.

Many historians have attempted to discern cycles in history, and generally, those attempts have failed. Those attempts were essentially misguided because they attempted to identify worldwide cycles or, failing that, cycles that apply to the entire Western world. Such attempts fail because, for example, it makes no sense to believe that a regional war in 17th century Ireland can meaningfully be related to a regional war in China or Africa at the same time.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The reason that Generational Dynamics works is that it does not attempt to define its 80-year cycle as worldwide. Quite the contrary, the cycles we're describing apply only to small regions, albeit regions that have been getting larger over the centuries. This is what the "Principle of Localization" is all about.

In this chapter and the next, we're going to expand the theory of Generational Dynamics in several ways. We'll describe the Principle of Localization, how to tell a crisis war from a mid-cycle or interim war, and how small regional wars expand into large world wars.

Historical scholars who reflexively criticize cyclical theories of history should understand this point about localization. What we're talking about in this book is simple common sense. When a society has a brutal, bloody, genocidal war (a "crisis war"), then the people of that small, local society decide "never again," and are willing to make compromises to avoid a repeat. When the people who remember the war die, then there's another crisis war.

So we're not claiming anything magic here -- that a war in one region somehow magically causes a war in another region. What we're claiming is simple human nature.

However, this simple observation has yielded enormously interesting results, and that's what this book is about.

|

Let's start with the adjoining map, created by Peter Turchin of

University of Connecticut for his analysis of the development of

Europe over two millennia. In order to do his analysis, he found it

necessary to divide Europe into 50 separate geographical units, taking

into account both terrain features (mountains, coastlines) and ethnic

divisions (language, religion) , with the result as shown.

, with the result as shown.

The Principle of Localization claims that each of these regions has its own 80-year cycle timeline, at least to start with. As the centuries pass, and regions merge, their timelines also merge. Even today, however, not all these regions are completely merged: At the very least, Western Europe, Eastern Europe and the Balkans are still on separate timelines.

Of course, to rigorously test Generational Dynamics, it would be necessary to show that the 80-year cycle applies to each of these 50 regions. That's a very big piece of work. However, in chapter 8 we do trace the timeline of Spain back to the 1300s and of England back to 1066; Spain and England present relatively clean examples because they're both somewhat isolated from the rest of Europe.

Having now explained how local regions must be considered separately, let's now discuss how separate regions still go to war together.

Few Americans are familiar with the ancient Ibo ethnic group or its

distinguished history. Consider a member of this group. He may be an

Owerri Ibo or an Onitsha Ibo in the Eastern region of Nigeria. In

Lagos, he is simply an Ibo. In London, he is Nigerian. In New York,

he is an African.

This example illustrates how the same person is viewed very differently different people. Each of the descriptions -- Owerri Ibo, Onitsha Ibo, Ibo, Nigerian and African -- identifies this person as part of a group he understands -- an identity group.

| It makes no sense to believe that a regional war in Ireland can meaningfully be related to a regional war in China or Africa at the same time. |

How should one view the intermittent civil war that's dominated Nigerian politics for decades? To a participant, a war is always an "us" versus "them" kind of thing. To the Ibo man we've been describing, the "us" consists of the Ibo and other tribes in the south and the "them" are the Fulani-Hausa tribes in the north.

To an American, the Nigerian civil war is just a bunch of local tribes fighting one another -- just as dozens of local groups fight among themselves around the world at any given time. With so many regional conflicts going on all the time, there's no reason why this particular one should draw the average American's attention.

Question: What must change before an American would become interested in the regional war in Nigeria?

Answer: Just point out the simple fact that this is a war between the Muslims in the north and the Christians in the south.

Suddenly, this is a much more important "us" versus "them" war. If you're a Christian, the "us" consists of the Christian fighters, and the "them" are the Muslims; to a Muslim anywhere in the world, these roles of "us" and "them" become reversed.

This simple little use of identity groups turns a simple, unimportant regional war into a portion of a major worldwide war stretching from Africa, through Europe and Asia, into Indonesia.

It's worth pointing out, in passing, that the identity group concept

is not new. A marvelous exposition of a related concept will be

found in the fourteenth century Arab politician and sociologist, Ibn

Khaldun. Khaldun's concept, asabiya, measures the

cohesiveness or solidarity of a group . An analysis by Peter

Turchin of University of Connecticut shows how Khaldun examined

numerous Muslim societies, to find that asabiya is the essence of

rendering one group superior to another in war. Khaldun shows that

frequently asabiya declines and dynasties disappear four generations

after the dynasty is established -- thus providing a kind of 14th

century basis for the 80-year generational cycle! Turchin's analysis

goes on to correlate asabiya to a number of geographical and ethnic

characteristics (coastlines, mountains, religion, language,

economics). He develops mathematical models that show specifically

how Europe was formed into nations, and, in particular, the influence

of the Roman Empire.

. An analysis by Peter

Turchin of University of Connecticut shows how Khaldun examined

numerous Muslim societies, to find that asabiya is the essence of

rendering one group superior to another in war. Khaldun shows that

frequently asabiya declines and dynasties disappear four generations

after the dynasty is established -- thus providing a kind of 14th

century basis for the 80-year generational cycle! Turchin's analysis

goes on to correlate asabiya to a number of geographical and ethnic

characteristics (coastlines, mountains, religion, language,

economics). He develops mathematical models that show specifically

how Europe was formed into nations, and, in particular, the influence

of the Roman Empire.

|

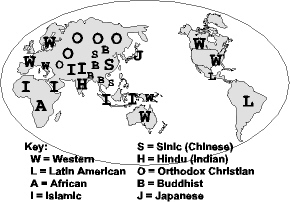

What are the major civilizations in the world today? Scholars

differ, but for our purposes we'll use the collection defined by

Harvard Professor Samuel P. Huntington in his book, The Clash of

Civilizations : Western, Latin American, African, Islamic, Sinic

(Chinese), Hindu, Orthodox, Buddhist, and Japanese.

: Western, Latin American, African, Islamic, Sinic

(Chinese), Hindu, Orthodox, Buddhist, and Japanese.

Huntington defines a fault line war to be one that takes place between two identity groups from different civilizations. (Since the phrase "fault line" is so compelling and so graphic, we'll use that term to describe other kinds of conflicts as well, such as the fault line between the North and South that led to the Civil War, or the fault line between the French and the Germans that led to numerous wars.)

As a practical matter, it's unlikely that a major fault line war will ever break out between the Latin American and Japanese civilizations. Both of these are purely geographical civilizational designations, and even if we imagine a scenario where some sort of conflict breaks out between these two groups, it's hard to see how it spreads into anything like a world war.

|

No, the fault line wars that are biggest, bloodiest and longest lasting are between identity groups based on religion. They rarely are settled except through genocide.

Huntington's book describes the potency of religious identity groups, and shows in detail radical leaders on both sides of a regional conflict use religious identities to expand the conflict into other regions sharing the same identities.

Here's how Huntington describes what he calls "the rise of civilization consciousness":

These processes usually begin sequentially, but they also overlap and

may be repeated. Once started, fault line wars, like other communal

conflicts, tend to take on a life of their own and to develop in an

action-reaction pattern. Identities which had previously been

multiple and casual become focused and hardened.... As violence

increases, the initial issues at stake tend to get redefined more

exclusively as "us" against "them" and group cohesion and commitment

are enhanced. Political leaders expand and deepen their appeals to

ethnic and religious loyalties, and civilizational consciousness

strengthens in relation to other identities. A "hate dynamic"

emerges ... in which mutual fears, distrust, and hatred feed on each

other. Each side dramatizes and magnifies the distinction between the

forces of virtue and the forces of evil and eventually attempts to

transform this distinction into the ultimate distinction between the

quick and the dead.

These processes usually begin sequentially, but they also overlap and

may be repeated. Once started, fault line wars, like other communal

conflicts, tend to take on a life of their own and to develop in an

action-reaction pattern. Identities which had previously been

multiple and casual become focused and hardened.... As violence

increases, the initial issues at stake tend to get redefined more

exclusively as "us" against "them" and group cohesion and commitment

are enhanced. Political leaders expand and deepen their appeals to

ethnic and religious loyalties, and civilizational consciousness

strengthens in relation to other identities. A "hate dynamic"

emerges ... in which mutual fears, distrust, and hatred feed on each

other. Each side dramatizes and magnifies the distinction between the

forces of virtue and the forces of evil and eventually attempts to

transform this distinction into the ultimate distinction between the

quick and the dead.It's important to note that the "processes" that Huntington describes include negotiation, compromise and containment, as well as intensification and expansion. A wide variety of processes are possible, because other nations drawn into a regional battle may be more interested in seeing the battle settled than in seeing it expand.

| The major civilizations today are Western, Latin American, African, Islamic, Sinic (Chinese), Hindu, Orthodox, Buddhist, and Japanese |

Good examples of these containment processes are the roles of America and Jordan today in the Mideast conflict between Israelis and Palestinians. Jordan is in the Muslim civilization, and America is in the (Judeo-Christian) Western civilization. Yet, both countries are more dedicated to mediating the conflict than expanding it.

Later, we're going to use the phrase "Identity Group Expansion," referring to the expansion process described above, to refer to the principle that wars expand by rallying other societies or nations in the same identity group.

Starting in 1990, a conflict broke out in the Balkan region of Europe. The war was characterized by "ethnic cleansing," mass murder of men who were then buried in mass graves, and mass rape of women, who were thus forced to bear children with the sperm of their conquerors. By 1995, America was sending thousands of troops in a peacekeeping role to end the hostilities.

Huntington provides a lengthy analysis of this conflict, which I'll summarize here. However, my main intent is to identify important aspects of the analysis that Huntington omits, but which can be analyzed using Generational Dynamics.

Imagine a map of Eurasia with three civilizations labeled on it: the Western (Judeo-Christian) on the left, the Orthodox on the upper right, and the Muslim civilization on the lower right. (We're omitting other civilizations for simplicity here.)

Now, where do these three huge civilizations meet? The answer is that they meet in the Balkans, with large populations of Catholics in Croatia, large populations of Orthodox Christians in Serbia, and large populations of Muslims in Bosnia and Albania.

Remarkably, these three groups lived together peacefully for decades in the Balkans. In many cases, they were friends and neighbors, living near each other, babysitting for each other's children, often intermarrying - just like any suburban neighborhood in America. That's why it was so remarkable to see how brutal and violent the Balkans war of the 1990s was. It was as strange and unexpected as if the citizens of Stamford, Connecticut, decided one day to rise up and start killing each other.

Huntington details violent acts on all sides, pointing out that the

violent acts began with the Albanian Muslims in the late 1970s. By

the late 1980s, Slobodan Milosevic was appealing to Serbian

nationalism . In a celebration in 1989, Milosevic lead one to

two million Serbs to commemorate the 600th anniversary of the 1389

conquest of Serbia by Muslim Turks. This illustrates how the

appropriate choice of "us" and "them" can inflame mass passions: it's

not Serbs versus Albanians; it's Serbs versus Muslims.

. In a celebration in 1989, Milosevic lead one to

two million Serbs to commemorate the 600th anniversary of the 1389

conquest of Serbia by Muslim Turks. This illustrates how the

appropriate choice of "us" and "them" can inflame mass passions: it's

not Serbs versus Albanians; it's Serbs versus Muslims.

In looking to use Generational Dynamics to enhance Huntington's analysis, we wish to consider two questions:

Let's look at these two questions.

Most Americans know little about the Balkan region of Europe, and yet because of its unique position as the meeting place of three major civilizations, it's one of the most critical regions of the world. It's worth remembering that World War I was the result of identity group expansion of the regional hostilities that broke out in the Balkans in 1914.

Huntington shows how identity groups rallied in the most predictable

ways in the Bosnian wars : Germany, Austria, the Vatican, other

European Catholic and Protestant countries and groups rallied on

behalf of Croatia; Russia, Greece and other Orthodox countries and

groups behind the Serbs; and Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Libya, the

Islamist international, and Islamic countries generally on behalf of

the Bosnian Muslims.

: Germany, Austria, the Vatican, other

European Catholic and Protestant countries and groups rallied on

behalf of Croatia; Russia, Greece and other Orthodox countries and

groups behind the Serbs; and Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Libya, the

Islamist international, and Islamic countries generally on behalf of

the Bosnian Muslims.

However, America was "a noncivilization anomaly in the otherwise universal pattern of kin backing kin." It should have supported just Croatia, its civilizational relation, but instead it supported both the Croatian Catholics and the Bosnian Muslims, siding against only the Orthodox Christian Serbs.

I don't think any Americans find it remarkable that we supported both the Croatians and the Bosnians against the Serbs. After all, when Serb president Slobodan Milosevic started implemented his "ethnic cleansing" program, the stories of mass genocide and rape by Serbs horrified Americans, so supporting the Bosnians as well as the Croatians seemed quite natural.

But if that's true, then why was America unique in doing so? Generational Dynamics provides some important insight into this question.

Each crisis war transforms a nation in a new way, and so a country takes on a new character during that 80-year cycle. This character can be entirely civilizational, or it can go beyond the purely civilizational.

The Great Depression and World War II transformed America from a country with a "laissez-faire" economy and a small government to one with a large government and a heavily regulated economy, and from an isolationist nation to "Policeman of the World." More specifically, America transformed itself into "Impartial Policeman of the World," in a sense almost rejecting the civilization paradigm.

This insight is important for policy planners as they try to assess the future "clash of civilizations" between Western and Islamic situations, because it shows that the civilization paradigm isn't monolithic. In other words, when the great "clash of civilizations" arrives, it's not certain that all Muslim countries will stick together on one side, and all Western countries will stick together on the other side.

The easiest way to see this is to note that there have been major intra-civilizational wars in the past -- as recently as World War II, when England sided with France against Germany. In the Napoleonic wars, England sided with Germany against France.

Based on history, it seems unlikely that all European countries will be on the same side of a future war, even if we're all from the same Western civilization. Today, we can only speculate, but we have to note that hostile attitudes between America and France have been hardening for some time, and show few of abating.

On the other side, we take note of the fact that Muslim country Iran is run by Islamic clerics, but has a population that regularly engages in large pro-American demonstrations.

Huntington analyzes the cause of the Bosnian war in the context of

wars worldwide between Muslims and non-Muslims, and the fact that "as

the twentieth century ends, Muslims are involved in far more

intergroup violence than people of other civilizations." He considers

several reasons -- the history of Islam, the difficulty Islam has

coexisting with other religions, and "Finally, and most important,

the demographic explosion in Muslim societies and the availability

of large numbers of often unemployed males between the ages of

fifteen and thirty as a natural source of instability and violence

both within Islam and against non-Muslims. Whatever other causes may

be at work, this factor alone would go a long way to explaining

Muslim violence in the 1980s and 1990s."

and the fact that "as

the twentieth century ends, Muslims are involved in far more

intergroup violence than people of other civilizations." He considers

several reasons -- the history of Islam, the difficulty Islam has

coexisting with other religions, and "Finally, and most important,

the demographic explosion in Muslim societies and the availability

of large numbers of often unemployed males between the ages of

fifteen and thirty as a natural source of instability and violence

both within Islam and against non-Muslims. Whatever other causes may

be at work, this factor alone would go a long way to explaining

Muslim violence in the 1980s and 1990s."

These factors all explain the causes of the Bosnian and other wars, but they don't explain the timing. All of these factors were true in 1970, 1980, 1990, and 2000, and yet the Bosnian war occurred at a particular time.

The same puzzle occurs with most other wars. You can look at various causes of the American Civil War -- differences over slavery, differences in lifestyle, economic issues -- but those causes don't explain why the war occurred in 1861, rather than 1850 or 1870.

The answer to these puzzles is explained by Generational Dynamics. The Civil War has previously been discussed at length (pp. [basics#71] and [americanhistory#117]), but with regard to the Bosnian War, note the following: The Bosnian war was a replay of the Balkan wars that occurred 80 years earlier. Albanian-Serbian relations degraded throughout the decade of the 1900s, and did again in the decade of the 1980s. Full-scale war broke out in 1912, and again in 1990.

It's true that there were other wars in the region before and since, but none were nearly as transformational. The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was created in 1918, and that was a major transformation. After World War II, Yugoslavia became a Soviet satellite, but remained a single Yugoslav state, without undergoing a major transformation as it had done in 1918. During the years from 1918 to 1990, there were other conflicts and skirmishes in Yugoslavia, but none with enormous transformational impact of the Balkan wars of the 1910s. It was only in the 1990s that a new major transformation occurred, as Yugoslavia itself fell apart.

Finally, with regard to other wars involving Muslims, we note that the entire Muslim world was transformed by World War I, starting with the 1908 coup by the "Young Turks" in Turkey, to the carving up of the Ottoman Empire in the 1920s. It's now 80 years later, and all these wars are being replayed in one way or another -- whether it's the intra-Muslim Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s, or the inter-civilizational war in the Balkans of the 1990s.

So Huntington and other historians can identify and discuss the causes of the Muslim wars of recent times, and the timing of these wars can be explained by the fact that they're occurring one 80-year cycle after World War I.

In the next chapter, we continue to explore this relationship between the causes of a crisis war and its timing, in order to further develop the theory of Generational Dynamics.