Dynamics

|

Generational Dynamics |

| Forecasting America's Destiny ... and the World's | |

| HOME WEB LOG COUNTRY WIKI COMMENT FORUM DOWNLOADS ABOUT | |

|

These pages contain the complete manuscript of the new book

Generational Dynamics: Forecasting America's Destiny,

written by John J. Xenakis.

This text is fully copyrighted. You may copy or print out this

material for your own use, but not for distribution to others.

Comments are invited. Send them to mailto:comments@generationaldynamics.com. |

|

Before 1500, Europe consisted of many small regions. One division into 50 regions is shown by the adjoining map that we reproduce from chapter 3.

By the Principle of Localization, each of these regions would have to be analyzed separately, showing how all their timelines eventually merged together, and that's way too much work for this book. That's a project for some history graduate student.

However, we can get our feet wet without immersing ourselves completely in the ocean. Because England is separated from the European continent by the English Channel, we can present a fairly clear timeline throughout its medieval period, starting from the Norman Conquest in 1066.

Likewise, Spain is in a corner of Europe all its own, and so it's fairly insulated as well, and we present a timeline for Spain starting from the 1300s.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

These two examples serve as responses to the claims from some that Generational Dynamics does not apply before the 1500s. In fact it does, provided that the Principle of Localization is observed.

From there, we can see how timelines merge throughout Europe, especially in the Thirty Years' War (1618-48) and the War of Spanish Succession (1701-14). After that, wars involving France, Germany and England recur every cycle with painful regularity, through World War II.

And as we've discussed in previous chapters, and will continue in chapter 9, Eastern Europe is on a different timeline, with World War I on its timeline, as well as more recent wars in the Balkans, Iran, Iraq and Turkey. The next war, which will involve all of Western Europe, Russia, and the Mideast, will serve to merge the West and East European timelines.

So let's begin with medieval Spain and England, and then move on to the major wars that merged the Western European timelines.

Spain provides a good, clear example of generational timelines during the medieval period, and it's an interesting example at that.

Spain is a good example for another reason: The Golden Age of Spain provides some interesting lessons for America today.

In many cases, a crisis war is a violent civil war (like America's Civil War, the bloodiest war in America's history).

The 1390s civil war in Spain was marked by especially violent anti-Jewish pogroms that were triggered by a serious financial crisis for which the wealthy Jews were blamed. Almost every crisis war ends with some sort of imposed compromise that unravels 80 years later, leading to the next crisis war.

The compromise that ended the 1390s civil war was an interesting one:

The Jews would convert to Catholicism, or else would be expelled.

During the next few decades, over half of the 200,000 Jews on the

peninsula formally converted to Catholicism .

.

Compromises of this sort only work for so long, but the failure of this compromise was especially ironic. The Conversos, as the converted Jews were called, were now officially Christian, bringing them further wealth and status. A large part of the Castilian upper class consisted of Jews and Conversos, naturally generating a great deal of class jealousy among the lower classes. It's typical for riots and demonstrations to occur during an "awakening" period, midway between two crisis wars, and that's what happened here. The riots against the Conversos began in 1449, and became increasingly worse as the old compromise began to unravel. Thus, an old fault line between the Catholics and the Jews was replaced by a new fault line between the old line Catholics and the Converso Catholics.

Those who remember America's most recent "awakening" period in the

1960s and 70s will remember the fiery rhetoric that demonstrators

used in the antiwar movement at that time. Johns Hopkins University

professor David Nirenberg found that the "anti-Converso movement"

rhetoric of 1449 and beyond was just as heated: "The converts and

their descendants were now seen as insincere Christians, as

clandestine Jews, or even as hybrid monsters, neither Jew nor

Christian. They had converted merely to gain power over Christians.

Their secret desire was to degrade, even poison, Christian men and to

have sex with Christian women: daughters, wives, even nuns ."

."

This is exactly what Generational Dynamics is all about. The generation of kids who grew up during the 1390s pogroms became risk-aversive adults who were willing to look for compromises to avoid new bloody violence. Thus, there were anti-Converso riots during the 1450s and after, but that risk aversive generation that grew up in the 1390s were still around to contain the problem, and look for compromises, to keep things from getting too far out of hand, despite the heated rhetoric. When that generation died, no one was left to look for compromises, and new pogroms began in the 1480s.

As the old compromise unraveled completely, the riots against the

Conversos got worse, and a common charge against the Conversos was

that they were "false Christians ." The most common charge

against Conversos was that of "Judaizing," that is, of falsely

pretending conversion and secretly practicing Jewish rites.

." The most common charge

against Conversos was that of "Judaizing," that is, of falsely

pretending conversion and secretly practicing Jewish rites.

This is what gave rise to the Spanish Inquisition. The idea was to have an official body empowered to determine whether those who had claimed to convert to Catholicism had really converted. As new pogroms began in the 1470s and 1480s, the Inquisition was particularly targeted to find the "Judaizers." At first, the Inquisition was directed specifically at Conversos, but later was extended to unconverted Jews. Thousands of Conversos and Jews were executed under the Inquisition, and entire Jewish communities were eliminated.

The new crisis war reached its climax in the year 1492, when three different things happened that affected Spain for the entire next 80-year cycle:

With regard to the last point, Muslims had crossed over to southern Spain from Africa as early as the 700s, and had conquered almost all of Spain. The Catholics had dreamed of reconquering Spain from the Muslims for centuries. The Reconquest was finally completed in 1492.

We now need to step back and look at the reasons why Spain became the most powerful nation in Europe during the 1500s.

For two very important reasons, Spain is unique among the West European countries:

Throughout history, some invasions are acceptable to the people being invaded and some are not. When the Romans conquered Spain in the second century BC, the Spanish initially resisted, but later adopted the Romans' cultural characteristics of family, language, religion, law and municipal government.

However, things were not so easy for the Muslims, when they conquered Spain in the early 700s. By that time, Spain was a clearly Christian society, and had no desire to convert to Islam.

Islam began in the Mideast in the early 600s. The Muslims spread rapidly all across Northern Africa, jumped the Strait of Gibraltar in 711, and soon conquered almost all of Spain.

Spain flourished under the Muslims, who built schools and libraries, cultivated mathematics and science, and developed commerce and industry.

| It was at this moment that the concept of manifest destiny sank deep into the Spanish conscience |

But the desire for "Reconquest" by the Christians was always foremost in the minds of the Spanish people. The Christians reconquered bits and pieces of Muslim-occupied territory over the centuries.

In 1469, Spain was united by the marriage of Isabella and Ferdinand, the Catholic Monarchs of two Spanish kingdoms, Castile and Aragon, respectively. Thus, the crisis war we described above, triggered by rioting against upper class Conversos and unconverted Jews, also had another component: there was to fierce infighting among other royal relatives of the two Monarchs. But Spanish unity prevailed, and in 1478, the Spanish Inquisition was authorized, with the purpose of investigating the sincerity of Muslims and Jews who claimed conversion to Christianity. In 1492, the Catholics were able to complete the Christian Reconquest of Spain from the Muslims.

As we've pointed out, a bloody, violent crisis war changes the

character of a nation, and the nation retains that character

throughout the next 80-year cycle. That's what happened with the

1480s civil war. Spain saw itself as the home of true Catholicism,

and saw itself as having the duty to spread Catholicism throughout

Europe. Thus, the crisis war that climaxed with the Reconquest and

the expulsion of the Jews in 1492 resulted in a new Catholic Spain.

"It was at this moment that the concept of manifest destiny - so easy

to take hold in any country at the height of its power - sank deep

into the Spanish conscience ," says Manuel Fernandez Alvarez of

the University of Salamanca. "The Spaniard felt he had a godly mission

to carry out, and this was to make it possible for him to withstand

bitter defeats in later years."

," says Manuel Fernandez Alvarez of

the University of Salamanca. "The Spaniard felt he had a godly mission

to carry out, and this was to make it possible for him to withstand

bitter defeats in later years."

During the 1500s, there were three factors that fed into this sense of manifest destiny:

Immediately after the Reconquest, Spain sent Columbus to find a new route to East Asia, and Columbus discovered America in 1492.

New discoveries and conquests came in quick succession. Vasco Nunez de Balboa reached the Pacific in 1513, and the survivors of Ferdinand Magellan's expedition completed the circumnavigation of the globe in 1522. In 1519, the conquistador Hernando Cortes subdued the Aztecs in Mexico with a handful of followers, and between 1531 and 1533, Francisco Pizzaro overthrew the empire of the Incas and established Spanish dominion over Peru.

These were heady discoveries in the days following the Reconquest, and yet Spain's "manifest destiny" plans might have led to nothing except for something that Spain itself considered to be a gift from God to help them achieve that destiny: The Spaniards were able to bring thousands of tons of silver and gold from the New World back to Europe.

This was Spain's Golden Age. Spain became wealthy, and led Europe in music, art, literature, theater, dress, and manners in the 1500s. It exercised military strength throughout Europe, and led the fight against the Protestant Reformation.

However, problems arose. Spain's imported wealth was wasted on consumption, with nothing saved or invested. The precious metals created price inflation throughout Europe. Once again, as usually happens in any society's generational cycle, the controls and restrictions that are imposed just after a crisis war become unraveled late in the cycle. Money was used to paper over Spain's own internal divisions, and to fund more military adventures.

In 1568, with the Inquisition becoming ever more intrusive, serious rebellions broke out among the Muslims who had remained in Spain after the Reconquest. This led to mass expulsions throughout Spain of Muslims, leading to exodus of hundreds of thousands of Muslims, even those who had become devout Christians.

In the midst of the increased turmoil, Spain attempted to continue to serve God with its military might.

Disaster came in 1588 when Spain decided to invade England, which had succumbed to the Reformation in 1533. The plan was to overthrow the Protestant Queen Elizabeth and install a Catholic King. Spain's huge Invincible Armada sailed up the English Channel and waited to be joined by transports with invasion soldiers. The soldiers never arrived. The English fleet trapped the Armada and scattered it. The Armada fled into the open sea, where a storm drove the ships into the rocks on the shores of Scotland.

The crisis war ending in England's defeat of the Spanish Armada was an enormous victory that signaled the decline of Spain as the leading military power in Europe.

This provides an important lesson for America today. Since World War II, this has been the Golden Age of America, and just as Spain felt obligated to spread Catholicism around Europe, we feel obligated to spread democracy around the world. Spain was too ambitious, and came to disaster; America may do so as well.

Because of its insularity, England has followed a fairly clean line of generational cycles that we trace here back to the Norman Conquest in 1066.

England wasn't entirely insular: England shared borders with at least two other regions, Wales and Scotland. However, it appears that it was England (rather than either Wales or Scotland) that initiated the crisis wars that forced the two regions to merge timelines with England and to merge physically with England, and so it's the English timeline that dominated the medieval period.

This insularity has also made it possible for Britain to advance ahead of other countries in other ways. Later in this chapter, as we discuss the transition of European governments from monarchy to parliamentary democracy, it's worth remembering that England had a parliamentary form of government as early as the 1200s. True, the Crown still had most of the power, and Parliament had to submit to the Crown's will almost always, but the fact is that because of the Parliament and Common Law, England has had internal peace for most of the time for centuries.

Let's briefly summarize the history of England during the medieval period.

England and France have probably been at war with each other for

millennia. We take up the battle from 1066, when the Normans of

northern France (Normandy), led by William the Conqueror, completed

their conquest of England from the Saxons .

.

With that, England and France were united, with Norman kings running both regions. This brought peace between the two regions for decades.

Naturally, a fault line developed among the kids born in England and the kids born in Normandy after the conquest. Their parents knew each other from before and during the war, but the kids had no personal connection with each other. As these kids reached their 20s, a generation gap would have resulted in an awakening.

The exact nature of the disagreements between the younger and older generations at that time is lost in history, but we can be pretty sure it had to do with taxes. In fact, William the Conqueror completed a national census called the Domesday Book in 1086, so that he could raise income and property taxes. The kids would have been unhappy about that, and might well have blamed not only William, but also his old friends back in Normandy.

Eventually, William died, as did the kids who grew up during the Norman invasion, leaving in charge the people born after the Norman Conquest.

William was followed as King by William II and then by Henry I. At

the death of Henry I in 1135, a succession dispute arose because

Henry left no male heir .

.

A civil war broke out between, on one side, those who wanted the original Norman conquerors and their descendants in England to retain control, and on the other side, those who wanted Normandy to retain direct control. (This was not unlike the context of America's Revolutionary War, which was really a civil war fought between descendants of the original English settlers versus those who wished England to retain direct control.)

| The Civil war among the Normans was not unlike the context of America's Revolutionary War |

The civil war was not resolved until 1154, when Henry II, a new Norman king from Anjou in Normandy, took the English throne. The adjective corresponding to the word "Anjou" is "Angevin," and so the new line of kings was called the Angevin line.

During the awakening period of Henry II's reign, there were dramatic

changes to make the law fairer . The Common Law required courts

to make rulings based on precedent, thus limiting its power to make

arbitrary rulings; and the jury system required a citizen's guilt or

innocence to be decided by his peers, not by a court official.

. The Common Law required courts

to make rulings based on precedent, thus limiting its power to make

arbitrary rulings; and the jury system required a citizen's guilt or

innocence to be decided by his peers, not by a court official.

Two different fault lines were exacerbated by these developments. First, there was the ancient fault line between England and Normandy (France); and second, there was the fault line within England itself, between partisans of the new Angevin kings and the Barons of the old order. The next crisis brought war across both of these fault lines.

Back at the end of the last civil war, it made sense that a king who had just been imported from Normandy should remain in control of Normandy as well. However, that made less and less sense as years went by and generations passed.

Starting in 1204, King John suffered a crisis of confidence when he

lost battles in Normandy, forcing him to cede control of most regions

of Normandy . This precipitated a renewed civil war with the

English Barons who had been paying high taxes to support that losing

war in Normandy.

. This precipitated a renewed civil war with the

English Barons who had been paying high taxes to support that losing

war in Normandy.

The crisis was resolved in 1815, when King John was forced to sign the Magna Carta, the great charter of liberties, which restrained the king's power.

An ambitious attempt to conquer Sicily in 1254 left the Crown

bankrupt. In 1264, a new civil war broke out between the Barons and

partisans of the king .

.

The problem was resolved in 1275, when the king was forced to accept a national assembly of king, lords and commons -- the first parliament.

However, the civil war moved westward to another region - Wales. By 1282, the king had conquered all of Wales, and imposed harsh conditions.

However, a mid-cycle war with Scotland failed, and in 1327, the Treaty of Northampton gave Scotland its independence.

During the awakening period, the English parliament was given increased powers.

The perennial war between England and France resumed in 1337, with the commencement of the Hundred Years' War, which was fought intermittently until 1453.

The first phase of that war was a major victory for the English,

thanks to technology. A 14,000 man English army wiped out a 50,000

man French army in 1347, thanks to advanced weaponry .

.

In centuries to come, wars of this type would be settled by some sort of international meeting that would set boundaries and assign spoils of war in such a way as to prevent war for another few decades. (See examples in this chapter of the Peace (treaty) at Westphalia, Treaty at Utrecht, Congress at Vienna, and so forth.)

No such mechanisms were available in 1347, however, so the war continued through a series of mid-cycle wars.

However, we can't ignore another major development: The Black Death

reached the continent in 1348 .

.

Nature provides one method -- sex -- to keep population growing rapidly, and three methods to keep population from growing too rapidly: war, famine and disease.

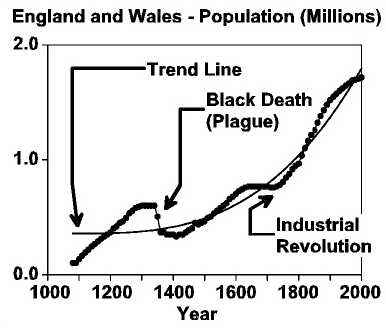

The effect of disease on population is shown dramatically by this graph. The Black Death (bubonic plague) struck the entire world at various times in 1334-49 and killed enormous numbers of people.

|

The Black Death turned out to have a major social effect, inasmuch as it killed commoners and royalty without any apparent distinction.

During the next awakening, numerous peasant rebellions took place all around Europe, including the Peasants' Revolt in England in 1381. This was a sign of things to come in the religious wars of the 1500s.

While the Hundred Years' war battles were being fought in France in the background, new wars were breaking out on English soil.

Tensions between king and parliament led to a new civil war in

1386 . It was resolved in 1400, but at that point, the war

shifted to Wales, which was taking steps to declare its independence.

Full-scale war took place between 1404 and 1409, at which time harsh

restrictions were placed on the Welsh people.

. It was resolved in 1400, but at that point, the war

shifted to Wales, which was taking steps to declare its independence.

Full-scale war took place between 1404 and 1409, at which time harsh

restrictions were placed on the Welsh people.

The Hundred Years' war continued as a series of mid-cycle battles. The last English victory over the French was at Agincourt, France, in 1415. After that, the English became less energetic in fighting the war. By contrast, France rallied in 1429, supposedly because of the spirit of the peasant girl, Joan of Arc. By the end of the Hundred Years' war in 1453, France had almost completely expelled England.

This civil war was fought over a new succession crisis, where members

of both the ruling Lancaster family and the York family wanted to be

the next king. The name "Wars of the Roses" is based on the badges

used by the two sides, the red rose for the Lancastrians and the

white rose for the Yorkists . Incidentally, the Yorkists won.

. Incidentally, the Yorkists won.

The awakening period that followed was dominated, as it was throughout Europe, by the Protestant Reformation, and the resulting religious wars.

However, the religious wars in England were postponed because the new Protestant religion was adopted by the king. King Henry wanted to dump his current wife and marry Anne Boleyn, but the Pope wouldn't grant the divorce. So King Henry, with the acquiescence of parliament, declared himself to be head of the Catholic Church in England, and granted himself a divorce. He married Anne Boleyn and later beheaded her - but that's a story for another time.

In addition, a 1536 Act of Union changed the status of Wales from a dependent territory to an equal partner in a union with England. Welsh citizens were represented in parliament, and had full rights as English citizens.

When Queen Elizabeth was crowned in 1558, she immediately moved to consolidate the position of the Church of England. This raised tensions with Spain that, as we've seen, was trying to fulfill its "manifest destiny" to spread Catholicism. Attitudes in Spain were pretty hostile to England anyway, because that woman whom Henry had divorced to marry Anne Boleyn had been a Spanish princess.

Spain had a plan: They'd get rid of Queen Elizabeth (somehow), and then the next in the line of succession would be Mary Tudor, Queen of Scots -- a Catholic.

Queen Elizabeth had a plan: Stall, stall, stall. Keep the Catholic Mary Tudor under control, but make sure she's OK. Hold off the inevitable Spanish invasion until England could build up its weak navy.

But destiny played a hand in 1568, when Queen Mary of Scotland was forced to flee for her life from her enemies in Scotland, and ended up safe and sound in Queen Elizabeth's prison.

Mary was imprisoned, but not helpless. When it was proved in 1587 that Mary was part of a plot to assassinate Elizabeth, Elizabeth was forced to execute Mary, and Spain was forced to launch the Invincible Armada to invade England in 1588. Elizabeth's plan had worked: she had stalled and used the time well to build a powerful navy which was able to defeat the overconfident Spain.

Britain's great civil war began with the Scottish rebellion in

1638 . By 1642, the war was engulfing all of England, with

parliament and the king serving as the main protagonists, battling

each other for power, and control of the army. The British Monarchy

was destroyed when the King was beheaded in 1649, and was restored in

1660 when a new king was crowned.

. By 1642, the war was engulfing all of England, with

parliament and the king serving as the main protagonists, battling

each other for power, and control of the army. The British Monarchy

was destroyed when the King was beheaded in 1649, and was restored in

1660 when a new king was crowned.

Once the monarchy was restored in 1660, the tensions between the Crown and parliament came back as well, since nothing had changed in terms of the balance of power.

By 1688, tensions had grown so great that there might have been another civil war, but now you can see once again the flow of history through generational analysis: There were too many people around who remembered the horrors of the last civil war, and didn't want to see another one.

Great things often happen in an awakening period -- the period midway between two crisis wars, and that's what happened in England. Just as President Nixon was forced to resign during America's awakening period in 1974, King James was forced to resign in 1688. Here's how it happened (complete with a sex angle):

James II was a Catholic King, not working well with a Protestant Parliament. The Parliament had allowed him to become King in 1685 because he was old, soon to die, and had no children except for Mary, who was Protestant and married to the Dutch Prince William. Thus, as soon as James died, the Protestant Mary would become Queen.

| The Dutch invaded and conquered England in 1688, in England's Glorious Revolution. |

Well suddenly, late in 1687, word spread that James' wife was pregnant, which would have created a new Catholic heir to the throne if the child turned out to be a boy. Well, it was a boy, born in June 1688, and the Parliament had already put steps into motion to get rid of James: They invited James' Dutch son-in-law William (Mary's husband) to invade England. When the Dutch army landed, late in 1688, James fled, headed to France, hoping that France's Catholic King would help him drive the Dutch army back. In something that the English at the time considered to be a miracle, James was captured by fishermen. He escaped, but by then it was too late. William and Mary were named King and Queen of England.

In fact, the English considered James' capture by fishermen to be only one of many miracles that year. They referred to the events of 1688 as the "Glorious Revolution." It was glorious because there was no war, no bloodshed, and because it settled the question of power sharing between the Crown and the Parliament.

There's a bit of real irony to the Glorious Revolution. The English like to point out that England was never invaded by a foreign power after the Norman Conquest until the German bombings in the two World Wars, but when they make that claim, they conveniently forget the Dutch invasion by Prince William. The fact that no shots were fired does not change the fact that the Dutch invaded and conquered England in 1688, in England's Glorious Revolution.

One more note: In 1693, the King and Queen established William and Mary College in America. The college broke its ties with England in 1776, but still retains the same name today.

In the 1500s, wars were still regional, rather than engulfing the entire continent, and crisis wars still occurred on different timelines. The religious wars were the context in which the different timelines were merged.

Corruption was widespread in the Catholic Church, and it's natural that any people suffering financial setbacks would blame the Catholic Church, and would adopt the Protestant religion as a means of protest. As a result, the Protestant religion spread rapidly in some regions, not in others, and religious fault lines began to develop.

In the region around Germany and Austria (the Habsburg Empire), there was a series of bitter wars in the 1540s between Protestants and Catholics. These wars were settled in 1555 with the Peace at Augsburg.

Crisis wars are often settled with a major compromise, typically by forcing people to accept fixed national or regional boundaries. Frequently, these compromises unravel over an 80-year period, resulting in the next crisis war.

As we'll see, that's what happened with the Peace at Augsburg. The

great compromise was a regional one -- that each region of the

Habsburg Empire would be ruled by someone of the prevailing religion

in that region (Catholic or Protestant). An interesting observation

is that the Peace at Augsburg recognized religious pluralism for the

first time in Europe , and was thus a first step to recognizing

full-fledged freedom of religion in America's Bill of Rights, 240

years later.

, and was thus a first step to recognizing

full-fledged freedom of religion in America's Bill of Rights, 240

years later.

|

Turning now to France, the crisis war occurred 20 years later and was punctuated by the St. Bartholomew's Night Massacre, an atrocity that is remembered today.

Like Germany, France was also a Catholic country when Protestantism started spreading in the early 1500s. Various clashes broke out frequently over the decades, and the major civil war between the Catholics and the Huguenots (the name adopted by French Protestants) began in 1562. Both sides were extremely violent, especially targeting each other's churches and clergymen and even lay people. (Attacks on civilians are a typical sign of a violent crisis war.)

The crisis climaxed on August 24, 1572, when Catholics massacred some 1,000 to 2,000 Huguenot civilians in Paris in a single night, known as the St. Bartholomew's Night Massacre. During the next two months, some 10,000 to 100,000 civilian Huguenots were slaughtered throughout the country, often in their own homes.

In the years that followed, some half million of the country's two million Huguenots fled to other countries. Many others renounced their Protestant religion, not being able to understand how God had deserted them.

The feelings generated by the massacre were greatly inflamed when the Catholics in Rome, led by the Pope, celebrated the deaths of so many "heretics" as a miracle, to be remembered as a holy event.

The massacre haunts France to this day, though some tensions were relieved when Pope John Paul made a plea for forgiveness and reconciliation in a visit to France in 1997.

With England, France, Germany and Spain on different timelines in the 1500s, it took the entire 1600s to merge the timelines of these countries, converging (as we'll see) on the War of Spanish Succession that began in 1701.

Germany's crisis war in the 1500s climaxed in 1555, and France's climaxed in 1572. This is a classic "merger of timelines" situation, and it's not surprising that the Thirty Years' War began in Germany in 1618, and France entered the war much later, in 1635.

The Thirty Years' War first began as a civil war in the Habsburg Empire (Germany and Austria), following the unraveling of the 1555 Peace at Augsburg.

We can identify a big financial crisis component to the Thirty Years' War, caused by the debasing of coins, and leading to the great "Tulipomania" bubble, as we'll see.

The financial crisis had, at its base, the price inflation caused by the precious metals that Spain imported from the New World during the Golden Age of Spain in the 1500s. After the disastrous destruction of the Invincible Armada by England, Spain rebuilt its Armada, but was forced to pull back many of its military adventures, especially as sources of precious metals in the New World began to peter out.

This led to financial hardship, but it doesn't take long for clever people to devise sneaky new methods for making money.

The habit of debasing coins had begun around 1600. The value of a coin was determined by the value of the precious metal in it. Princes and clergymen started to debase the coins by substituting cheap metal for good metal, or by reducing their weight. Trading in these coins became increasingly speculative during the "unraveling" period, since one could never be sure whether a coin was debased, or how much it was worth. By 1618, debasement was widespread throughout the Habsburg Empire, causing widespread financial hardship.

So by 1618, we had the two factors needed to forecast a new crisis war -- a financial crisis and a generational change, the latter coming from the death or retirement of people who were around during the Peace at Augsburg.

The German civil war began.

|

The reason that the Thirty Years' War lasted 30 years is that it comprised several different wars, because of the merger of timelines. It's as if we described World War I and World War II as a single war running from 1914 to 1945.

The Thirty Years' War was extremely destructive. It laid waste large

parts of central Europe. Population declined from 21 million in 1618

to 18 million in 1648 . It started in Eastern Europe in the

early 1620s; then it spread to the north and enveloped Denmark and

Sweden in the late 1620s and 1630s.

. It started in Eastern Europe in the

early 1620s; then it spread to the north and enveloped Denmark and

Sweden in the late 1620s and 1630s.

Recall that France's timeline was about 20 years behind Germany's timeline in the religious wars of the 1500s, and so it's not surprising that France entered the Thirty Years' War 20 years later than Germany did.

By the 1630s, Spain and Germany were closely linked by religion and marriage. A Habsburg cousin was ruling Spain through marriage.

More important, the two empires shared a common religious vision of serving God by spreading Catholicism and defeating the Protestants.

Furthermore, the Netherlands was also controlled by the Habsburg Empire.

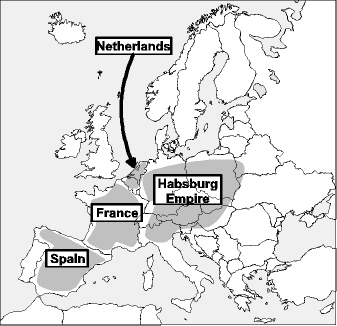

So, if you take a look at the adjoining map, you can see that France was pretty nervous, being surrounded on all sides by the Habsburgs.

Furthermore, the financial health of Europe continued to decline. Spain was becoming increasingly in debt, as the supply of precious metals from the New World continued to decline, and the debasement of coinage around Europe was unabated.

This was the time of one of the most remarkable financial crises in recorded history, the "Tulipomania" bubble. Tulips were the "high tech" products of the day, and people were buying and selling tulips at increasingly high prices, just as people bought and sold high tech stocks at increasingly high prices in the 1990s. The Tulip Mania bubble is described in detail in chapter 6.

| This was the time of one of the most remarkable financial crises in recorded history, the |

France's religious wars occurred in the 1550s-60s, with the brutal St. Bartholomew's Massacre occurring in 1572, and so the generational change in France occurred in the 1530s.

France declared war on Spain in 1634 and on Germany in 1635. This extremely brutal war, which also involved Denmark and Sweden as allies of France, lasted until 1648.

The war ended with the Peace of Westphalia, agreed in 1648. It was called the "Peace of Exhaustion" by its contemporaries.

What was the great compromise that settled this war? Mainly, it

settled by treaty the boundaries between France and its ally Sweden

on the one hand and the Habsburg possessions on the other hand.

About 250 separate German states were recognized as sovereign .

.

Unfortunately, setting a boundary by treaty does not mean that the boundary is going to be observed "on the ground." Populations swell or move around, and these demographic changes can make old boundaries subject to renewed conflict.

A particular provision made the Netherlands an independent country. This became a particular issue half a century later, in the War of Spanish Succession.

The War of Spanish Succession broke out 87 years after the start of the Thirty Years' War, and 52 years after the treaty at Westphalia was signed. This war merged the timelines of the major West European countries, and put them onto the same timeline.

The war was triggered by the death of the King of Spain in 1700. Since he was childless, the person who would inherit Spain was not known until his will became known at his death. Today, it would be considered a peculiar thing to have one person inherit an entire country from another person, but that in fact is what happened in those days.

Even more bizarre by today's standards is this: Because of numerous marriage alliances, the country might have gone to either French or German royalty, or split between them. It would not be known until the will was read. In addition, since France and Germany were long-term enemies, the will could have an enormous effect on the balance of power in Europe. How's that for a situation?

| Today, it would be considered a peculiar thing to have one person inherit an entire country from another person |

Well, when the will was read, it turns out that Spain was bequeathed to the grandson of the King of France, who then became King of Spain, and so Spain became allied with France, where previously it had been allied with Germany. It was previously Spain's alliance with Germany that triggered France's entry into the Thirty Years' War, and prompted the final settlement with the Peace at Westphalia.

Bequeathing Spain to French royalty completely unraveled the Westphalia Treaty, and the War of Spanish Succession began.

Like the Thirty Years' War, this war was filled with genocide and

atrocities. It ended in 1714 with the Treaty at Utrecht, which the

statesmen of the time signed because they wanted to avoid for as long

as possible another violent conflict such as the one that had just

ended .

.

England and France remained enemies for centuries, until World War I, and were at war somewhere in the world almost constantly.

England and France ceased active direct warfare on the European continent until the 1790s, but they were still virulent enemies, and fought on other battlefields, especially in America and India, in the meantime.

The largest of these wars in America occurred when the French formed an alliance with the American Indians, with the purpose of driving the English out of North America. The French had formed outposts in Canada, and south along the Mississippi River. The Seven Years' War ensued (known in America as the French and Indian War), from 1756 to 1763. France was decisively defeated not only in America but also in India, leaving England as the preeminent power in the world, by the time the two countries signed the Treaty of Paris in 1763. France later retaliated by supporting the colonists fighting England in America, but the next full-fledged war between England and France didn't occur until the French Revolution.

Tensions remain between England and France to this very day.

Now let's move on to the next crisis war between France and Germany.

Many historians say that the American Revolution inspired the French Revolution, and some even imply that it caused the French Revolution. The reasoning is that, in supporting the Americans against the British, the French became acutely aware of the Declaration of Independence and the ideals it represented, and wanted to implement those ideals in France as well.

We'll discuss America as a cause of the French Revolution below, but as you might expect, this book is going to present an entirely different analysis of the causes of the French Revolution.

Most of all, the French Revolution occurred because of a generational change. The last great war had been so violent that the statesmen who had signed the treaty ending it did so specifically saying that they never wanted to see another war like that again. Well, those people were dead, or at least gone. New people were in place, people who were tired of what was happening at that time.

And what was happening at that time?

In the 1780s, France was in the midst of a major financial crisis. France had developed an enormous national debt -- money it owed to other monarchies, to the Church, to wealthy individuals, and so forth. Just like a person who uses his MasterCard to pay off his Visa bill, France was running out of time. The debt had been increasing for decades, and was reaching a critical point by the 1780s.

Even worse, there was a shortage of food. Taxes were high to pay off the debt, causing sharp inflation in the price of food, with starvation among the working classes.

In the end, the country was put into the hands of a sort of bankruptcy court. And this was done not because of some great moral or ethical epiphany, but because the country was bankrupt. The French Revolution was thus a financial decision more than anything else.

The "bankruptcy court" was called the Estates-General, and it consisted of three groups of "estates": The First Estate was the clergy; the Second Estate was the nobility; and the Third Estate comprised the common people. (Today, we use the phrase "fourth estate" to refer to the newspapers.) Within a few months, this turned into a National Assembly and Legislative Assembly which fulfilled its bankruptcy court responsibilities by wresting power from the monarchy and passing numerous reform laws -- many of which were inspired by the experience in America where, just a few brief weeks earlier, the new Constitution had been adopted.

We will not attempt here to list all the fun facts of the French Revolution, such as how the National Assembly got locked out of its usual meeting place and, fearing a conspiracy, met in an abandoned tennis court and passed new laws targeting the supposed conspirators.

Instead, we'll focus here on the issues that make this crisis like the other crises that we've considered in this book -- a financial crisis in combination with a generational passing, giving rise to desire for retribution, resulting in a series of shocks and surprises leading to war.

When Enron Corp. in 2001 became America's largest bankruptcy, Americans demanded retribution -- in the form of sending Corporate CEOs to jail.

| Terror was considered a positive thing during the Reign of Terror because the people being terrorized were considered to be bad people |

Within 1790s Paris, the principal tool for retribution was not jail, but the guillotine. The word "terror" was coined during this time, and during the Reign of Terror, 1793-94, some 200,000 people were executed by guillotine. And it's worth remembering that while "terror" is a negative term today, it was considered a positive thing during the Reign of Terror, because the people being terrorized were considered to be "bad" people.

To understand the feelings of rage and retribution, imagine if today we started executing people in Washington D.C. with public beheadings that everyone could see. Now imagine this happening 200,000 times in two years -- the number people executed by guillotine in France during the Reign of Terror.

I mention this to remind you, again, that this is how genocide occurs. Whether we like to admit it or not, it's part of the natural human condition. In modern times, we've had huge acts of genocide in Cambodia in the 1970s and in Bosnia in the 1990s, and genocidal acts are going on today in Africa.

When money is at stake, the feelings of retribution spread quickly. All of Europe was controlled by monarchies, locked together through intermarriage and through promissory notes. Much of Europe had a lot at stake in restoring France's monarchy, and with the War of Spanish Succession now 70 years past, the statesmen who vowed never to have another such war were dead and gone. War felt right again.

Marie Antoinette, Queen of France and wife of France's King Louis XIV, was the brother of the Emperor of Austria, so it's not surprising that, after deposing the King and Queen, France's new Legislative Assembly declared war against Austria in 1792, especially since the Emperor of Austria declared his intention to sponsor a counter-revolution to restore the monarchy in France. A French invasion of Austrian land was quickly beaten back by Austrian forces, and Austria threatened to burn Paris to the ground if the French Royal family were hurt.

By the end of 1792, a new coalition formed by the European Monarchs, including Austria, Prussia, Great Britain, Spain, Russia, Sardinia, Tuscany, the Netherlands Republic and the states of the Holy Roman Empire (Germany) had formed to sponsor the counter-revolution.

The violent Reign of Terror, then, was fomented to punish counter-revolutionaries. The King was among the first to be guillotined (in Jan, 1793), and his wife was felled several months later (in October).

By 1797, the war had mostly settled down, but it couldn't end there. Unlike mid-cycle wars, crisis wars do not end until there is someone has forced a resolution -- agreement that painful compromises must be accepted so that the fighting can stop.

However, this crisis was not settled. Before 1789, Western Europe

consisted of a chain of over 300 political units with different

principles of organization , locked together by numerous

treaties, marriages, and financial arrangements. France was the

biggest and most important link in that chain, and when it

disappeared through bankruptcy, the entire chain had to fall apart.

So war was really a foregone conclusion.

, locked together by numerous

treaties, marriages, and financial arrangements. France was the

biggest and most important link in that chain, and when it

disappeared through bankruptcy, the entire chain had to fall apart.

So war was really a foregone conclusion.

The agent of this war was Napoleon Bonaparte, a brilliant soldier and general in the French army, who staged a coup d'état in 1799 to become military dictator.

Through a series of brilliant military campaigns, France's army under Napoleon overran almost all of Western Europe, effectively ending the interlocking chain of monarchies, and consolidating the French Revolution throughout Europe. He only came to grief when he invaded Russia to capture Moscow -- a campaign we discussed in detail in chapter 5. By 1815, the 300 political units had been reduced to 38 states.

A skeptical friend asked me sarcastically, "So you're saying that you could have predicted the French Revolution in 1750?"

The answer is "No," but this question provides a convenient launching pad to discuss the issue of exactly what we can and cannot predict using the Generational Dynamics methodology that we've been applying.

Suppose an alien from a distant galaxy had landed in Europe in 1750. Let's suppose that he was a mathematician who knew the mathematics that we know today, as well as the generational methodology for analyzing history on his own faraway planet, and wanted to apply what he knew to Earth in the year 1750. What could he have predicted?

First, he could have predicted that the age of monarchies would have to come to an end at some point in the not too distant future. That is, he could not have specifically predicted the French Revolution, but he could have predicted that its principal effect would have to come about one way or another.

Why is that? The answer has to do with complexity, a quantity that can be measured mathematically. The interlocking fabric of monarchies was becoming too complex to match realities "on the ground." As populations grew and moved around, the "ownership" of these populations would have to change to match the populations themselves, but that could not happen when inheritance determined "ownership," which then depended on who married whom, who had children with whom, and who owed money to whom.

In chapter 11, we'll show how the mathematics of complexity theory can predict the end of any form of centralized control over an entire economy, whether by dictatorship, monarchy, socialism, or communism, and that capitalism and representative government (republicanism) are the only organizational forms that can survive forever. But for now we simply make the observation that the end of the monarchies could have been predicted in 1750.

What about time frames? Could the alien visitor in 1750 have predicted that the European monarchies would collapse in the early 1800s?

I believe so, but only if we assume that the alien had the power to fly around in his space ship and gather a great deal of demographic information about Europe over the preceding 100-200 years. By using this information, the alien could have used his spaceship's computer to forecast how quickly the complexity of the interlocking relationships would grow, and would then be able to show that within 50-75 years it would become too complex to continue.

Before ending this speculation, let's consider one more question: What happens if the alien remains on earth for 32 years, and is in France in 1782. Could he have predicted the French Revolution at that time?

Here, the job of predicting is quite a bit easier. France's financial situation was already dire, and it could have been predicted that France was going into bankruptcy: there was no other possible outcome by 1782.

What does going into bankruptcy mean for France in the 1780s?

The answer to that question would depend on the mood of France and its people. If the country had been in a mood of "deterrence, compromise and containment," then the King and Queen might have felt forced to find a way to repay its debts -- spend a lot less money, force the clergy and the nobility to give up some of their lands to be used for debt repayment, and so forth.

In fact, the first moves of 1789 were to do just that -- by impaneling the General Assembly, France was trying to find a peaceful means to pay its debts.

And that might have worked a few decades earlier, when the violence of the War of Spanish Succession was still in people's minds. The French people might have swallowed their pride and set up a program of fiscal austerity to put France's finances back on course.

But too much time had passed, and once the important generational change is made, then desires for compromise always become desires for retribution, and so event spiraled into a war that engulfed the entire continent. And the alien in France in 1782 could reasonably have predicted, at that time, that some such scenario was likely.

The important analogy is, of course, to today, 2003. The generational change has occurred, the Nasdaq has crashed, as have the World Trade Center towers. There is a mood of retribution today, not only in America, but in many other countries as well, and that's why we can predict that some series of as yet unknown events will lead us and the Islamic world to a major war in the next few years.

When analyzing the aftermath of a crisis war, it's usually best to start with the painful compromises that were made so that the fighting could finally stop (like slavery in the American Revolution). Those compromises often get revisited in the next awakening, and especially in the next crisis war (like slavery in our own Civil War).

To analyze what happened in Europe during the nineteenth century, we have to understand what the great compromises were at the truce for the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars.

What were the painful compromises that everyone accepted in order to settle the French Revolution? The complex web of interrelationships between monarchies around Europe had collapsed from the sheer weight of its complexity.

There were two major areas of painful compromises adopted by the major European powers at the Congress of Vienna in 1815:

Both of these compromises had to be revisited -- the first in the awakenings of the 1840s, and the second in the wars of the 1860s.

The words "revolutionary explosion" have been used to describe the riots, revolts and demonstrations that were widespread in Europe in that one year, 1848.

There had been numerous rumblings before that. As usual, we expect awakenings to be 15-20 years after the previous crisis war is settled, because it's at that time that the "generation gap" appears -- the people who are too young to have personal memory of the war start to become adults.

And indeed, various rebellions did start in the 1830s. One of them -- the 1830 rebellion of Belgium against Dutch rule -- led to Belgian independence a few years later.

But the Belgian situation was unique. For the most part, as is typical of awakenings, no boundaries changed until the wars of the 1860s. What did happen is that the revolutionary awakenings forced many gradual changes throughout Europe. These changes included things like major reform laws in England, and the 1830 overthrow and replacement of Charles X, latest King of France.

In fact, the only reason that 1848 is so noteworthy is because so many rebellions occurred in that one year -- in England, France, Hungary, Germany, Italy, and other locations.

What was so special about that particular year? What was the event that caused so many youngsters of the postwar generation to rebel at once?

Presumably, the commonality was triggered by the Irish potato famine, which began in 1846. The famine produced massive starvation in Ireland, and a deep recession throughout Europe in 1847. All the rebellions of 1848 would have happened sooner or later, but the potato famine, focused them all on a particular year.

Of particular interest is that Karl Marx published his Communist Manifesto in the same year (though under a different title at the time). Communism and socialism took hold in much the same way a religion might have taken hold in other times. In chapter 7, we examined the lives of Jesus, Mohammed and the Buddha to show how religions begin in awakening periods. The experience of Communism shows what might happen after that.

Communism and socialism started to spread among a number of disaffected groups; trade unions were particularly targeted. Communism became especially popular in Paris, where proponents associated communism with the French Revolution and its true revolutionary meaning, before the monarchy was restored in 1815. Communism's greatest victory came in Russia, where it was adopted as the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, during World War I. This illustrates how the ancient religions might themselves have become popular: creation by a charismatic founder during an awakening; spread in popularity; adoption by a society during a crisis war. Communism of course only lasted one 80-year cycle after adoption -- it effectively ended with the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991. In another time, it might have transmuted into a religion, and lasted for years.

The Crimean War is on the East European timeline, leading to World War I. It was a crisis war for Russia and Turkey. We'll discuss the Crimean War in chapter 9.

An interesting fact from the West European viewpoint is this: Both England and France fought in the Crimean War as a mid-cycle war, and it was the first major war where these two countries fought as allies.

The Wars of German Unification, which began 74 years after the beginning of the French Revolution, are little discussed in history books, but these wars, especially the Franco-Prussian war, were the crucial 19th century wars on the West European timeline leading to World War II.

Because of its strategic position in central Europe, Germany's borders have always been under constant pressure from all sides.

In preceding centuries, when Germany was known as the Habsburg Empire or the Holy Roman Empire, the boundaries of the empire were always in flux and were modified by many wars, both crisis wars and mid-cycle wars.

If you want to understand World War II and Hitler, forget most of what you've learned in school. You have to imagine yourself sitting in the middle of Germany as the centuries pass, and looking around in all directions. Whether it's France in the east, Russia in the west, Denmark and Sweden in the North, or the Muslims in the southeast, you always had to fight someone for land. WW II was just a continuation of that.

The 1815 Congress at Vienna, which ended the Napoleonic wars, was like many of the treaties we've been discussing -- a temporary band-aid on a never-ending problem. It finalized the end of the Habsburg Empire, and left the Germanic people scattered in various different regions.

A need for the unification of all German people into one state was felt almost immediately after the treaty, but it was not until the revolutions of 1848 that the deep support for unification became undeniable. At that time, in the midst of a severe recession, popular uprisings in Berlin, Vienna and elsewhere drove some regional leaders from office and elicited promises from others for a common German constitution.

Who would lead the German unification? There were two major Germanic empires at the time, Prussia and Austria, and they competed with each other for the leadership role.

Adding to the atmosphere was a kind of ghost: Louis-Napoleon

Bonaparte, nephew of Napoleon I, took power in France as Emperor

Napoleon III in a coup d'état in 1852. This was a shock to

the people of the British public, who feared another era of

Napoleonic conquest. However, the people of the British public were

incredulous when Napoleon III sought friendship with England .

This marked a dramatic change into British-French relations after

centuries of warfare, and the two countries were allies in the

Crimean War of 1854-56.

.

This marked a dramatic change into British-French relations after

centuries of warfare, and the two countries were allies in the

Crimean War of 1854-56.

Into this atmosphere came Otto von Bismarck, an obscure Prussian diplomat who became Chancellor of Prussia in 1862. History records Bismarck as both master politician and brilliant military tactician, in that he seems to have snookered just about everybody, while building up and using his army to achieve his goal of German unification under Prussia.

In an 1864 war with Denmark, Prussia and Austria wrested two German territories from Denmark, and Bismarck used the opportunity to enlarge the Prussian army. Then in 1866, he provoked Austria into declaring war on Prussia, and defeated Austria with his enlarged army. Finally, in 1870, he provoked France into declaring war on Prussia. In both cases, he gained political advantages the sympathy generated when another country declared war on Prussia, and he gained territory by actually winning both wars.

This war was a disaster for France. German forces overran and occupied France for months -- something that was repeated 70 years later in World War II. It was followed in 1871 by a violent civil war known as the French Commune -- resulting in 30,000 killed, the end of France's Second Republic, and the beginning of the Third Republic.

In addition, France was forced to cede the regions of Alsace and Lorraine to Germany. These territories, which were adjacent to the German territories, had been made part of France by the Treaty of Utrecht 57 years earlier, but now they were made part of the new German Reich.

World War II has been covered elsewhere in this book (pp. [americanhistory#203], [localization2#126] and [easteurope#184]), and won't be treated again here.

The history of these two countries is clear: They've been warring with each other for centuries, with crisis wars every 70-80 years or so: Thirty Years' War (1635-48), War of Spanish Succession (1701-14), Napoleonic Wars (1793-1810), Wars of German Unification (1860-71), World War II (1938-45). The only thing that's surprising is that it never occurs to anyone that things won't be different this time.

However, there's a strange historical twist in progress this time. In the past, England was allied with one of the countries and opposed to the other. There is a historical reason given for this: England always allies itself with the opponent of the country that is threatening to conquer all of Europe. Thus, England opposed Napoleon's France, and Hitler's Germany.

So what's happening today, with Germany and France appearing to line up against England in the war against Iraq? The historical twist is that the Germans and the French see England and America trying to take over the world the way the French or the Germans used to try to take over Europe. The generational change has already occurred throughout Western Europe, and there is a severe recession in progress. The attitudes of the Germans and French will continue to harden in the next few years, and they may continue to harden against England and America.

This is all very, very speculative of course. Still, it's the direction we currently appear to be headed in, and it is a possible scenario. The Generational Dynamics forecasting methodology (see page [localization2#52]) with a regular current attitudes analysis will detect how this is playing out, long before any actual actions are taken.