Dynamics

|

Generational Dynamics |

| Forecasting America's Destiny ... and the World's | |

| HOME WEB LOG COUNTRY WIKI COMMENT FORUM DOWNLOADS ABOUT | |

|

These pages contain the complete rough draft manuscript of the new book

Generational Dynamics for Historians,

written by John J. Xenakis.

This text is fully copyrighted. You may copy or print out this

material for your own use, but not for distribution to others.

Comments are invited. Send them to mailto:comments@generationaldynamics.com. |

In a previous chapter (p. [intro#210]) we discussed the question of what "genocide" is, from the point of view of Generational Dynamics, emphasizing the fact that out definition wasn't the standard legal or dictionary definition.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

We're now going to turn to the question of the "causes of war," and the Generational Dynamics analysis won't exactly correspond to the historians' meaning.

Actually we'll be focusing specially on crisis wars. We have no particular quibble with the historians' view of the causes of non-crisis wars, but for crisis wars the situation is completely different.

When talking about crisis wars, we will use the following terminology:

First, there's the political cause of war. This is the cause of war that historians usually point to, although there may be disagreement.

What we've found is that every war has a political cause -- or several political causes. And we've found that for non-crisis wars, the political cause is usually the right one. In non-crisis wars, the politicians make a decision, usually based on some sort of logical reasons, they're usually fairly public about the reasons, and they go to war for those reasons.

But for crisis wars, the political cause, more often than not, is inadequate as an explanation. Indeed, the political cause is often more a pretext than a reason. Non-crisis wars come from the politicians, but crisis wars come from the people. Crisis wars are unrestrained and genocidal. Crisis wars are based on emotions, especially hatred.

Thus, for crisis wars we look for a visceral cause of war, something that would make someone want to leave the comforts of home and go out and kill someone. Why did the Hutus go out one day and rape, torture, kill and dismember a million Tutsis in Rwanda in 1994? There's no political explanation for that, although one can be found if you try hard enough. (Some people blame the massacre on identity cards that the Belgian colonizers had once required.)

We use the word trigger to refer to the event, often a surprise event, that causes hostilities to begin. Some people will call it the "cause" of the war, but it's really a catalyst, not a cause.

Some examples of triggers are: That assassination of the Archduke Francis Ferdinand at Sarajevo on June 28, 1914 triggered WW I; a plane crash triggered the 1994 Rwanda war; the Thirty Years' War was triggered on May 23, 1618, by the "Second Defenestration of Prague" (when two politicians were thrown out the window of a castle into a ditch).

The last word we'll introduce is agent. For example, many people will say that Hitler caused WW II, but as we explained in detail in our last book, WW II would have occurred with or without Hitler. (When someone tells me that Hitler caused WW II, I usually follow up by asking him if he knows why Hitler decided to bomb Pearl Harbor.) We would call Hitler an agent that led WW II.

Incidentally, we use the term "agent" in other environments as well. For example, if Thomas Edison had never been born, then the light bulb would have been invented by someone else at almost exactly the same time. If Martin Luther King had never been born, then someone else would have led the civil rights movement at the same time. Thus, Thomas Edison and Martin Luther King were "agents of change," but were not the "causes of change."

|

As described earlier, there are three mid-cycle periods between crisis periods: the austerity period, the awakening period, and the unraveling period. It's during the unraveling period that individual rights have the highest political priority, and problems are resolved with the maximum intent of compromise and containment.

The crisis period begins with a generational change - when the people who lived through the last crisis war all disappear (retire or die), all about the same time. In America, this appears to have started in the late 90s, and taken effect around 2000.

During a crisis period, the national attitude changes dramatically. When a new problem arises, instead of evoking a desire to contain the problem and compromise, it evokes visceral feelings of anxiety, terror and fury throughout the population.

I noticed this even before 9/11, at the outpouring of national fury against all CEOs after the Enron scandal in Fall of 2000. If there had been a guillotine in Washington in 2000, then the people would have sent every CEO in the country to the guillotine (as in the reign of terror in France in 1793). Then after 9/11, Bush's immediate response was to invade Afghanistan, a response which was universally supported. I've always considered the reaction to the Enron scandal and the reaction to 9/11 to be two aspects of the same phenomenon that occurs during a crisis period: A widespread desire for justice and revenge instead of compromise and containment.

So, in today's America, we see two different reasons for the visceral anxieties that create a desire for revenge that can lead to the next crisis war:

When you look at these visceral causes, you can see why a generational change is required. People who had lived through the Great Depression would not become as terrified by a financial crisis. People who had lived through the horrors of WW II would not be as terrified by a single terrorist act that killed 3,000 people, about 8% of the number of people killed each year in traffic accidents.

But once that final generational change takes place, you're dealing with a population that, once again, is capable of being viscerally frightened and anxious, with a desire for revenge.

So when we look for the causes of a crisis war, what we're looking for are not the political causes, but the visceral causes: What is it that's making the population so frightened and anxious that they're willing to consider genocidal war to resolve the problem.

The whole subject of the causes of war led to a very vigorous online discussion of the specific causes of the American Civil War.

The cause of the American Civil War is commonly given as "slavery."

Sometimes this cause is expanded by saying that "the cause of the Civil War was to abolish slavery." This is silly, of course, since it was the South, not the North, that started the war.

My problem is that I can't figure out how you go from slavery to the civil war. Consider the following:

So, it seems possible to list slavery as "a" cause of the Civil War, but the claim that slavery is "the" cause of the Civil War, or even "the most important" cause of the Civil War cannot be easily supported.

When I look for the cause of a crisis war, I look for something deeper. I want to know the visceral reason why someone decided to pick up a gun or caused someone else to pick up a gun in order to kill someone else.

In looking for the cause of a war, especially a crisis war, I look for "visceral fear and fury": Fear over threats to one's life, threats to one's way of life, threats to the existence of one's nation or identity group, and fury at those who are blamed for those threats.

It's only this kind of "visceral fear and fury" that can lead to a crisis war.

To this end, I originally believed that the Panic of 1857 had to be the "real" cause of the Civil War, and I said so in my previous book. The plausible explanation was that the South blamed the North for the economic difficulties, and the North blamed the South for having the economic advantage of slavery.

The Panic of 1857 caused thousands of businesses to go bankrupt; the effects were international in scope (like the 1930s depression), and the unemployment rate in parts of New York City went has high as 90%. The problem was that I couldn't find any real historical evidence supporting the view that it caused the Civil War.

Tolstoy wrote War and Peace in the same time frame as the Civil War, In describing the "causes" of Napoleon's war against Russia, he was obviously stumped. Here's what he wrote:

It naturally seemed to Napoleon that the war was caused by England's intrigues (as in fact he said on the island of St. Helena). It naturally seemed to members of the English Parliament that the cause of the war was Napoleon's ambition; to the Duke of Oldenburg, that the cause of the war was the violence done to him; to businessmen that the cause of the war was the Continental System which was ruining Europe; to the generals and old soldiers that the chief reason for the war was the necessity of giving them employment; to the legitimists of that day that it was the need of re-establishing les bons principes, and to the diplomatists of that time that it all resulted from the fact that the alliance between Russia and Austria in 1809 had not been sufficiently well concealed from Napoleon, and from the awkward wording of Memorandum No. 178.

It is natural that these and a countless and infinite quantity of other reasons, the number depending on the endless diversity of points of view, presented themselves to the men of that day; but to us, to posterity who view the thing that happened in all its magnitude and perceive its plain and terrible meaning, these causes seem insufficient.

To us it is incomprehensible that millions of Christian men killed and tortured each other either because Napoleon was ambitious or Alexander was firm, or because England's policy was astute or the Duke of Oldenburg wronged. We cannot grasp what connection such circumstances have with the actual fact of slaughter and violence: why because the Duke was wronged, thousands of men from the other side of Europe killed and ruined the people of Smolensk and Moscow and were killed by them.

I have exactly the same problem when faced with descriptions of slavery as the cause of the Civil War. To paraphrase Tolstoy, "We cannot grasp what connection slavery has with the actual fact of slaughter and violence: why because Lincoln was elected, hundreds thousands of American men from the North and South killed and ruined the people of Gettysburg and Atlanta and were killed by them."

Tolstoy reminds us that if we're going to ascribe a political reason to the cause of war, then we're going to end up with multiple causes, since different groups have different political views. One thing that I find really objectionable about saying that slavery was "the cause" of the Civil War is that it's a North-centric point of view. The North won the war, so naturally they get to say what caused the war, but that might simply be a pretext.

This is a very important part of the Generational Dynamics methodology. In order to distinguish crisis from non-crisis wars, then you MUST look at the war from the point of view of each of the belligerents.

One thing that Generational Dynamics makes clear is that a war is very personal, especially a crisis war. If A and B have a war, historians may describe the war, and may discuss the "causes" of the war, but from the point of view of A and B, there are always two completely different wars. It's like a married couple having an argument over money or sex or anything else. The man and the woman may be having two completely different arguments without even realizing it.

The same is true of a war, especially a crisis war. From the point of view of an outsider, the belligerents may be fighting "a war," but from the point of view of the insiders, they're fighting two completely different wars, possibly without even realizing it.

So if we're trying to identify the causes of the American Civil War, at the very least you have to ask the South what THEY think are the causes.

It's true that slavery was a big part of the South's issues, as shown by the 1860 South Carolina Declaration of Causes of Secession:

We affirm that these ends for which this Government was instituted have been defeated, and the Government itself has been made destructive of them by the action of the non-slaveholding States. Those States have assume the right of deciding upon the propriety of our domestic institutions; and have denied the rights of property established in fifteen of the States and recognized by the Constitution; they have denounced as sinful the institution of slavery; they have permitted the open establishment among them of societies, whose avowed object is to disturb the peace and to eloign the property of the citizens of other States. They have encouraged and assisted thousands of our slaves to leave their homes; and those who remain, have been incited by emissaries, books and pictures to servile insurrection.

So slavery was an issue for the South, as we already knew, but this paragraph makes it clear that slavery was a "cause" in a completely different sense for the South than it was for the North.

It's worth pointing out here that Southerners believed that the North came to the table with unclean hands anyway. They pointed out that the factory economy of the North was more cruel in many ways than slavery -- unemployed people could starve and elderly people had no one to care for them. This was contrasted, as we pointed out with respect to Lincoln's proposal to end slavery in 30 years, to the fact that even elderly slaves in the south still had a home and people to take care of them. So the Southerners argued that, however bad slavery was, the Northern factory life was worse.

I'm going into detail on this because in Generational Dynamics it's very important to look at wars and their causes from both points of view. In particular, since it's the South that started the Civil War, it's impossible to discern the "cause" of the Civil War without understanding the Southern viewpoint.

With regard to slavery, South Carolina's argument was that the North was violating the commitments which led the Constitution to be adopted. But South Carolina had long considered the North to be violating that same Constitution in other areas.

In fact, South Carolina had threatened to secede before. The South was furious over tariff acts passed in 1828 and 1832, claiming that these tariffs harmed the South but poured money into the North to pay for their factories. John C. Calhoun of South Carolina wrote a long series of essays advocating a policy of "Nullification" of the tariff laws, on the grounds that they violated the Constitution, and showing how the South could secede from the Union if the North denied the Nullification policy. Although the Nullification crisis and the secession threat was contained at that time, it was Calhoun's ideas on tariffs that were used 30 years later for an entirely different issue - slavery.

The Southern resentment over economic issues ran very, very deep, as shown by a speech that Representative John Reagan of Texas gave on the floor of the House of Representatives on January 15, 1861. In speaking to Northern leaders in general, he said:

"You are not content with the vast millions of tribute we pay you annually under the operation of our revenue laws, our navigation laws, your fishing bounties, and by making your people our manufacturers, our merchants, our shippers. You are not satisfied with the vast tribute we pay to build up your great cities, your railroads, and your canals. You are not satisfied with the millions of tribute we have been paying you on account of the balance of exchange, which you hold against us. You are not satisfied that we of the South are almost reduced to the condition of overseers of northern capitalists. You are not satisfied with all this; but you must wage a relentless crusade against our rights and institutions. . . .

"We do not intend that you shall reduce us to such a condition. But I can tell you what your folly and injustice will compel us to do. It will compel us to be free from your domination, and more self-reliant than we have been. It will compel us to assert and maintain our separate independence. It will compel us to manufacture for ourselves, to build up our own commerce, our own great cities, our own railroad and canals; and to use the tribute money we now pay you for these things for the support of a government which will be friendly to all our interests, hostile to none of them."

My point in going into all the above is to show that to say slavery is the "cause" of the Civil War doesn't make sense. There is simply no way to go from "slavery" to the massive slaughter that occurred in the Civil War.

It's worthwhile now to repeat a portion of the quote from Tolstoy's War and Peace that appeared above: "To us it is incomprehensible that millions of Christian men killed and tortured each other either because Napoleon was ambitious or Alexander was firm, or because England's policy was astute or the Duke of Oldenburg wronged. We cannot grasp what connection such circumstances have with the actual fact of slaughter and violence: why because the Duke was wronged, thousands of men from the other side of Europe killed and ruined the people of Smolensk and Moscow and were killed by them."

Tolstoy wrote those words in the 1860s, and he may have also been wondering exactly the same thing about the Civil War. He might also have felt that it was incomprehensible that a problem like slavery could only be solved by massive slaughter and violence, when there were political solutions available.

We are proposing to answer that question in the following way:

So, for a crisis war, we have to look for a visceral cause that goes beyond the pure political goals. This is the only way to answer Tolstoy's question.

The generational paradigm specifies that once the final generational change occurs, and the people in the previous cycle's Artist generation disappear (retire or die), then the people left behind, who had no personal experience with the last crisis war, are highly likely to feel insecure and vengeful when a threat arises.

What we have to do is find something that will cause people to want to pick up a gun and kill people. We're not looking for a abstract political cause, but something so pressing and immediate that a man will want to pick up a gun and kill people to protect his family.

In the case of the Civil War, there are several possibilities why Southerners might have felt that the kind insecurity and vengefulness that was necessary to motivate them to initiate the Civil War:

Both of these reasons are financial and they're plausible. In the case of the French Revolution, a financial crisis caused the Reign of Terror, in which anyone formerly associated in any possible way with an aristocrat was put to death by guillotine. In America, the Enron scandal in 2001 caused the people to want to see every corporate CEO, whether guilty or not, jailed (if not guillotined).

In the case of the Civil War, there's a much more plausible explanation than a financial crisis.

The key to the dilemma can be found in a sentence of the South Carolina Declaration of Causes of Secession quoted above:

They have encouraged and assisted thousands of our slaves to leave their homes; and those who remain, have been incited by emissaries, books and pictures to servile insurrection.

Slave rebellions had been a concern almost from the beginning of the Republic, as the result of a massive 1791 slave rebellion in Santo Domingo that resulted in some 60,000 deaths.

America's first major slave insurrection occurred in 1800 when an army of 1,000 slaves, led by slave Gabriel Prosser, gathered with a plan to assault Richmond. The plan was thwarted by a black informer, and Prosser and 34 of his followers were hanged.

The pace of slave rebellions picked up in the 1820s, but the best-known is Nat Turner's rebellion of 1831. Here's a description:

On 22 August, Turner and about 70 recruits began a two-day rampage. They killed Turner's master and about 70 others. Some decapitated children (some of the slaves might have been drunk); Turner himself killed only one white. Many blacks chose not to join Turner because they sensed the futility of his effort. Indeed, the revolt was soon crushed. Turner managed to escape and hid out in the woods for 30 days before being caught. In the search to find him, 100 Virginia slaves were slaughtered. Turner was hanged. His uprising had been the most serious in the country to date. It so shook Southern states that they passed more stringent laws related to slaves, increased censorship against abolition, and made military preparations to halt further uprisings. ["The Almanac of American History p. 225"]

Here we see that the problem - slave insurrection - was handled by containment and compromise, as in all generational awakening and unraveling periods. The slaves were punished, and new laws were passed.

By the 1850s, the generational change into a crisis period was occurring. The people who had grown up during the violent Revolutionary War (the "Artist" generation) were retired or gone, and a slave insurrection produced much more anxiety. This is similar to America today: The numerous terrorist attacks, including the massive 1993 World Trade Center bombing, had little effect on Americans, but the 2001 attack traumatized the entire country.

The slave insurrection incited by John Brown in 1859 affected Americans of that day just as the 9/11 attack affected us. Here's the description:

With support from leading abolitionists, [John] Brown then conceived of a plan for establishing a stronghold in the Appalachian Mountains where escaped slaves and freed blacks could take refuge and then lead an armed uprising throughout the South. He rented a farm near Harper's Ferry, Virginia, and from this base he launched an attack with 21 men on October 16, 1859. He seized the town and the U.S. Armory there, but the local militia kept them under siege until a troop of U.S. Marines, led by Robert E. Lee, assaulted the engine house where Brown and his followers were making their last stand. Ten of them were killed, and the wounded Brown was captured. Tried and convicted of treason, Brown was hanged in Charlestown on December 2. If his raid failed, Brown's eloquent defense during the trial convinced many Northerners that the abolition of slavery was a noble cause that required drastic, possibly violent action. His last prediction that "much bloodshed" would follow proved to be right. Although his violent tactics were not approved by many (and were discreetly disowned by the prominent abolitionists who had encouraged him), Brown became something of a martyr. He inspired the words to a marching song that was the unofficial anthem of the Union troops, "John Brown's Body lies A'mouldering in the Grave." ["The Almanac of American History p. 275"]

Americans of the day were traumatized by this terrorist act, and Southerners particularly were terrified by the insurrections and infuriated at the Northerners, whom they blamed for inciting the insurrections.

The following account in Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, The end of slavery in America, by Allen C. Guelzo, Simon & Schuster, 2004, pp. 16-17, describes the situation:

Behind the slaveowners' rage at Lincoln lurked the dread not only that Lincoln meant emancipation but that emancipation meant insurrection and race war on the model of the Nat Turner slave revolt in 1831 or the massacres of white planters by their former slaves in San Domingue in 1791. Lincoln's election followed by little more than a year the attempt of the conscience tortured abolitionist, John Brown, to begin a slave uprising by seizing the weapons stored at the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. No matter that the raid failed, that Brown was swiftly tried and hanged, or that Lincoln publicly condemned Brown. "When abolition comes by decree of the North," predicted Georgia supreme court justice Henry L Benning, "very soon a war between the whites and the blacks will spontaneously break out everywhere." The kind of apocalypse Benning prophesied touched every racial and sexual anxiety of the white South. The race war would be fought "in every town, in every village, in every neighborhood, in every road." The North would take advantage of this turmoil to intervene in favor of the blacks, and the result would be the extermination or exile of the whites-"so far as the men are concerned, and as for the women, they will call upon the mountains to fall upon them." One planter in Maury County, Tennessee, convinced himself in February 1861 that "a servile rebellion is more to be feared now than [it] was in the days of the Revolution against the mother country," when the British recruited and armed runaway slaves to fight their former American masters in South Carolina. Henry William Ravenal was surprised to find so "much alarm among the people of servile insurrection" and wrote for the Charleston Mercury on "the necessity of vigilance on the part of our people against the secret plottings & machinations of the fanatic abolitionists, who will surely come among us in friendly guise to tamper with our negroes." In Texas, fires in Dallas, Denton, and Pilot Point sent fearful whites in pursuit of slave rebels who planned "to burn the houses and kill as many of the women and children as they could while the men were gone." Within a month, as many as fifty blacks and whites had been executed by home guards and vigilante mobs.

Finally we have it. We see the sense in which slavery was the "cause" of the Civil War. We finally see the visceral link that led Southerners from the election of Lincoln to picking up a gun to get ready to start killing.

What about the economic factors? Yes, they must still be part of the fabric of the war. The Panic of 1857 devastated the North, and the Federal taxes and tariffs were doing enormous damage to the economy of the South.

A financial crisis can be thought of as dry underbrush that feeds a war. If the North and South had been wealthy, the there would have been far less energy for a war, even in the face of servile insurrection. Men who have no way to feed their families except by joining the army will do so, and energetically if the war is a crisis war.

So I've come to agree that slavery was "the cause" of the Civil War, but not slavery in the political sense. It was slavery in the form of a visceral fear and fury of servile insurrection.

This is the answer to the question I asked above, paraphrasing Tolstoy: "We cannot grasp what connection slavery has with the actual fact of slaughter and violence: why because Lincoln was elected, hundreds of thousands of American men from the North and South killed and ruined the people of Gettysburg and Atlanta and were killed by them."

What about other causes -- political causes and economic causes? Every war has political causes, but people and nations don't want to admit the visceral and economic causes of war. No country wants to admit, "We went to war because we were afraid," or "We went to war for money." A political cause becomes a pretext for war, and is rarely the real cause.

Obviously, servile rebellion is not the most common visceral cause of war. That would be poverty and hunger.

In this section we're going to show genocidal war is part of being human: Because the population grows faster than the food supply.

Life is a zero-sum game in the sense that if one person lives, then some other person must die, since there isn't enough food for both.

One of the craziest damned things is that everyone says that Malthus was wrong, even though you can pick any day in any year for the last century or more, and there will have been 20-40 wars going on at the time.

In 1798, Thomas Roberts Malthus, published his Essay on Population in London, where it was an instant best seller. He showed mathematically that the population grows faster than the food supply, and concluded that there would always be famines killing people.

Now, Malthus made some mistakes. His math wasn't quite right, but it's still true that the population grows faster than the food supply. But his biggest mistake was the conclusion that famines would be the main vehicle that brought the population down.

Nature provides one method -- sex -- to increase population, and three methods -- famine, disease and war -- to decrease population. There are occasional famines, and there were massive deaths from the Black Death (Bubonic Plague) in 1347 - 1350. But those are rare examples. War, especially genocidal crisis war, is the most common method.

Sex and crisis war are the Yin and Yang of "survival of the fittest." The most successful tribes, societies, nations, religious groups or ethnic groups are the ones that can spawn the greatest number of children while exterminating the greatest number of other tribes, societies, nations, religious groups and ethnic groups.

|

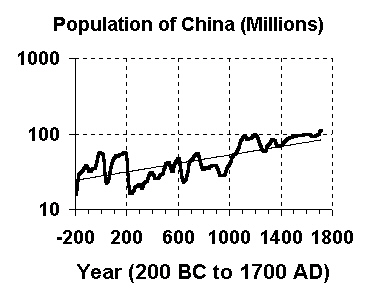

The adjoining graph of the population of China shows wild ups and downs. The straight line is the best fitting exponential growth trend curve (a straight line when graphed on a logarithmic scale). When the population goes up, we can assume that the Chinese were winning crisis wars against their neighbors, and perhaps enslaving them and taking their food. When the population does down, we can surmise that the Chinese lost a crisis war, or that there were civil wars where they killed each other off.

But why was Malthus wrong about famines and war? Let's now answer that question.

Malthus' views are rejected by almost everyone because we haven't seen the massive famines that Malthus predicted. Pundits claim that Malthus' predictions have been invalidated by technology in the form of the "Green Revolution," that has produced enough food to keep up with population growth.

The Green Revolution began in 1944 when the Rockefeller Foundation founded an institute to improve the agricultural output of Mexican farms. This produced astounding results, so that Mexico went from having to import half its wheat to self-sufficiency by 1956, and by 1964, to exports of half a million tons of wheat. In the 1960s, the Green Revolution had similarly spectacular results, especially in India.

when the Rockefeller Foundation founded an institute to improve the agricultural output of Mexican farms. This produced astounding results, so that Mexico went from having to import half its wheat to self-sufficiency by 1956, and by 1964, to exports of half a million tons of wheat. In the 1960s, the Green Revolution had similarly spectacular results, especially in India.

The problem with the Green Revolution is that it's a one-shot deal. You can move a given country's agriculture to the latest technology only once. After that, they'll have to invent new technologies to obtain further crop yields.

How fast do crop yields grow once a country has already been converted to the latest technology? To answer that question, I wanted to get a kind of "steady state" figure for the rate of increase of food production that would be independent of things like the green revolution. So I went to the USDA statistical service <http://www.usda.gov/nass/"> and obtained the "bushels per acre of wheat" from 1866 to 2003. This figure grew from 12.1 to 44.2 during that period, which is an annual growth rate of 0.96% per year. Thus, I've been using 0.96% as a kind of benchmark figure for the growth of food availability each year.

Next, I wanted to get an estimate of the world's annual population growth. To get this estimate, I went to the United Nations database of population information at http://esa.un.org/unpp/index.asp", and got the following world population table:

Year Population

---- ----------

1950 2 518 629

1955 2 755 823

1960 3 021 475

1965 3 334 874

1970 3 692 492

1975 4 068 109

1980 4 434 682

1985 4 830 979

1990 5 263 593

1995 5 674 380

2000 6 070 581

2005 6 453 628

This represents an average annual growth rate of 1.72% per year.

In support of this figure, take a look at the CIA Fact Book http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/ which gives the population growth rate on a country by country basis.

Here are some rate of growth figures for some Western countries:

United States 0.92%

United Kingdom 0.3%

France 0.42%

Germany 0.04%

Israel 1.39%

These figures show that Western countries have a fairly low rate of population growth.

Now look at some Muslim countries:

Syria 2.45%

Saudi Arabia 3.27%

West Bank 3.3%

Gaza Strip 3.89%

Pakistan 2.01%

This shows that the population in Muslim countries has been growing several times faster than Western countries. If you want to understand why we're heading for a "clash of civilizations" world war, then forget all the nonsense about politicals and hurt feelings and saving face and just look at the population growth figures above. They tell the entire story.

The problem of food versus population is well shown by the experience of the People's Republic of China since it was formed in 1949.

During the 1950s, Mao Zedong's Communist collectivization program destroyed China's agricultural production, culminating in the Great Leap Forward of 1958-60, and a man-made famine that starved tens of millions of people. Building on that low base, and taking advantage of a Chinese "Green Revolution," China increased agricultural production steadily until the 1990s, despite a reduction in available farmland of 1/3 during that 40 year period, to erosion, construction of buildings and roads, and desertification. [[ http://publish.gio.gov.tw/FCJ/past/04122471.html ]]

Since 1998, grain production has fallen from 510 million tons to just over 400 million tons in 2004. This has required massive and increasing imports of grain into China.

The following table gives all the relevant figures, including the rates of growth for 11 years versus rate of growth for the last five years:

China: Production of Wheat and Coarse Grains, 1993-2005

-------------------------------------------------------

Popu Land Produc Total Ending

lation Area Yield tion Imports Consumed Stocks

------ ---- ----- ------ ------ ------- ------

1993/94 56.0 4.0 223.6 5.6 214.0 149.5

1994/95 1.219 55.1 3.9 213.6 16.6 219.8 158.0

1995/96 56.2 4.0 226.7 15.5 221.9 177.6

1996/97 58.7 4.3 251.9 4.8 228.6 200.7

1997/98 58.1 4.1 238.0 3.5 230.6 204.2

1998/99 58.8 4.3 253.2 3.4 235.6 221.3

1999/00 1.275 58.4 4.3 251.1 3.4 238.1 227.1

2000/01 53.1 4.0 213.6 2.6 240.7 194.7

2001/02 52.1 4.1 216.1 3.1 241.6 162.1

2002/03 51.9 4.3 221.0 2.2 241.6 126.7

2003/04 49.3 4.3 211.1 5.3 244.6 88.1

2004/05 1.322 49.3 4.6 225.4 10.0 246.0 72.3

------ ---- ----- ------ ------ ------- ------

Rate 0.81% -1.1% 1.3% 0.073% 1.3% -6.4%

5 yr Rate 0.73% -3.3% 1.4% -2.136% 0.65% -20.5%

Units:

Population: Billions of people

Land Area: Millions of hectares of land (1 hectare = 2.47 acres)

Yield: Tons of grain per hectare

All other fields: Millions of tons of grain

File: hist_tbl.xls from:

http://www.fas.usda.gov/grain/circular/2005/02-05/graintoc.htm

http://www.fas.usda.gov/grain/circular/2005/02-05/hist_tbl.xls

Population: http://esa.un.org/unpp/index.asp

Note the following points about the above table:

These figures are important to all of us because food prices have increased 30% (thirty percent!!) worldwide in 2004.

This has had a tremendous impact on poor populations around the world, especially in Muslim countries. Why especially in Muslim countries? Because those are the countries where population has been growing the fastest, at 2-4% per year. These food price increases are hitting Muslim countries especially hard.

As for China itself, we can see it unraveling before our eyes. Day-to-day events, including regional rebellions, secessionist provinces, migrant workers, high food prices, high rust belt unemployment, addiction to a bubble economy, and unraveling of Mao's social structure, portray a country that's headed for a civil war. We can't predict exactly when this will occur, but the table shown above indicates a country that's unraveling faster and faster, so we expect a crisis civil war in China to begin sooner, rather than later.

The number of war deaths exploded in the 20th century. In this section, we'll explain that this is happening because of advances in medicine, especially in reducing child mortality.

The following graph shows the patterns of war deaths for the last few centuries.

for the last few centuries. (We'll see this graph again on page [cycles#1183], when we talk about Kondratiev cycles.)

(We'll see this graph again on page [cycles#1183], when we talk about Kondratiev cycles.)

|

Notice the footnote in the above diagram, indicating that the death rates for the two World Wars should be ten times as high as shown on the graph.

Reading the figures from the graph, we can see that the death rate per 100,000 population at the major peaks is:

1623-1648 (Thirty Years War) 80 1688-1713 (War of the Spanish Succession) 80 1792-1815 (Napoleonic Wars) 80 1914-1918 (World War I) 300 1937-1953 (World War II) 700

So the peak death rates were fairly constant for several centuries, and then suddenly spurted up by a factor of ten in the 20th century. How could that possibly have happened? Almost every growth quantity in nature grows exponentially, so something like this requires an explanation. The adjacent cartoon, from the Chicago Public Library web site, should give you a clue. It appeared around 1918 and it bemoans the fact that 20% of babies die prior to their second birthday, almost always from a preventable disease. |

|

This graph shows dramatically how infant mortality has decreased, from 73% survival in 1870 to 88% survival in 1910 to 99% survival in 1999.

The result of this drastic reduction in infant mortality is a "youth bulge" -- a much larger percentage of the population is younger.

Let's compare the Napoleonic wars (1700-1714) to WW I (1914-18). Napoleon mobilized two million men, but in WW I, the Allies mobilized 40 million men and the Central Powers mobilized more than 25 million men.

Now, granted that the two regions we're discussing aren't identical, but the difference of 2 million to 65 million is quite remarkable. The population would have grown by a factor of about 4 between those two wars, but the number of soldiers mobilized for war increased thirty-fold. How is that possible?

That's possible because of the youth bulge. The infant mortality rate was probably around 50% at the time of Napoleon, and was 12% at the time of WW I. The population increased by a factor of 4, but the population of war-age males was many times larger.

(This example requires some additional analysis - to tie it into the population vs food supply paradigm.)

Infant mortality continues to decrease, as the following graph from a U.N. report shows:

|

The advances in medicine in the last two centuries have been amazing, but they've had the effect of reducing the number of people who die from disease. That's good, I suppose, but it means that a lot more people have to die from war, because there's only so much food. And, in particular, the decrease in youth mortality has exacerbated this problem, by making a larger percentage of the population young males.

The population of the world today is about 6.5 billion. But if you extrapolate from 1950 to get the population today that would be supported by the amount of food today to get the same amount of food per person as in 1950, then you get about 3.8 billion.

That means that the coming "clash of civilizations" world war should be expected to result in billions of war deaths. The fact that so few people have died from disease means that so many, many more people have to die in war.

As we've said, people who say that Malthus was wrong are nuts. His basic finding that population grows faster than the food supply was absolutely correct. Malthus may have gotten some of the details wrong, especially his prediction that the result would be famines, but the basics were right.

Many people don't understand what effect the Malthus problem has on society. Most people think, "As long as there isn't a famine, the Malthus problem hasn't yet been realized."

The result is actually war, not famine. The actual process that occurs instead of famines is tied into the generational cycle. I call this process the "Malthus effect."

The Malthus effect applies to every nation, every society, at all times.

After a genocidal crisis war, there's plenty of food for everyone, since the population has been reduced. In the decades that follow, the population grows faster than the food supply.

Since population grows faster than the food supply, on both a regional and worldwide basis, it means that food becomes increasingly scarce, even though the total food production is increasing. And since food becomes increasingly scarce, the cost of food steadily increases.

So, for example, if a bowl of rice costs one hour's wages in 2000, then it might cost two hours' wages in 2001, and three hours' wages in 2002. Each year, the cost of food increases, meaning that people have less to spend on clothing, shelter, and other things.

Thus, the Malthus effect affects not only food, but an entire lifestyle. As the cost of food increases, year after year, a population becomes poorer and poorer, because they have less money to spend on other things besides food.

So the Malthus problem is not some far off problem that will cause a famine decades from now; it's actually a problem that occurs every single day, as the cost of food increases every day.

This problem becomes acute in regions where there are "market-dominant minorities." This phrase refers to places where there is a large population in poverty living in the midst of a minority, usually of a different race or religion, that controls most of the wealth.

Here are some examples:

|

Incidentally, this example illustrates the problem of food distribution. Ever since the US intervened in Haiti in 1994, the US has sent billions of dollars of aid to Haiti, and yet the population is poorer than ever. The country's leaders have simply dissipated the aid for their own purposes.

|

The relation between money and civil war is shown by the above graph, from a recent United Nations report . This graph shows the relationship between a country's average GDP and the risk of civil war.

. This graph shows the relationship between a country's average GDP and the risk of civil war.

The purpose of the UN report was, of course, to motivate the United States and other wealthy countries to find a solution to worldwide poverty. Since that goal is mathematically impossible to meet, for us the above graph is further proof that the world is headed to world war.

Severe poverty can, of course, occur at any phase of the generational cycle, though it's obviously more likely in the Awakening and Unraveling periods than in the Austerity period.

A wealthy minority is never as evil as the political opposition claims. In the Austerity period following a genocidal crisis war, all political groups and generations unite in their determination that nothing so horrible should ever happen again. Thus, there are always plans to make sure that everyone has adequate food and shelter, and that's always much easier than before the war because of the reduced population.

This is especially true in colonization situations. The colonial powers of the 1800s believed that colonization was a win-win situation: the colonial powers would bring investments and factories and agricultural techniques and medicine to the colonized people. These people would then have jobs to manufacture goods for export, which would earn them money so that they could be self-sustaining. It's a perfect solution, especially after the colonial region has just had a crisis war, and needs the "guidance" of the more experienced colonial power.

But it goes wrong because the population grows faster than the food supply, creating poverty. You start having patches of poverty during the Awakening period, and increasingly into the Unraveling period, often causing rioting or low-level violence that's handled by police actions.

If the low-level violence gets bad enough, then a political solution is sought, usually by giving the impoverished majority greater control over the political process. A typical solution is to arrange for the President of the country to be someone from the poor majority.

Unfortunately, there's never a political solution to a mathematical imbalance. The population continues to grow faster than the food supply, so the cost of food continues to increase, and so poverty continues to increase. The problem of helping the poor becomes overwhelming. The people in the wealthy minority develop a "bunker mentality," and keep more and more to themselves.

It's difficult, though not impossible, for people in the poor majority to break through and gain wealth or political power. If someone from the minority does break through, then he'll soon join the bunker occupied by the wealthy minority. This translates into bribery, corruption, fraud, and other techniques. The people involved are not necessary evil people (though they may be); it's just that the poverty problem is mathematically insoluble.

|

Today we're seeing this right before our eyes. In the analysis of China in the previous sections, we can see that China is depending on its bubble economy to suck up as much food as possible, to feed its huge unemployed and migrant population. This depends on exports to America, which depend on purchase of American debt. The situation is becoming worse and worse, and it will take only a moderate perturbation to send the entire system out of control.

At least China has a relatively low population growth rate. But not so the Muslim countries, whose population is growing at the rate of 2-4% (or more!) per year. The price of food increased by 30% in 2004, and this has hit the poor Muslim communities especially hard.

We're at a unique time in history, about 60 years after the end of World War II, when every country is experiencing the same generational change at the same time: The people in the generation that lived through WW II are all disappearing (retiring or dying) all at once, and are being replaced by the people in the generation born after WW II. Furthermore, the entire world's population is growing faster than the entire world's food supply.

There have been few crisis wars in recent decades. There was Cambodia in the 1970s, Iran/Iraq in the 1980s, the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s, and a few other smaller ones. Unfortunately, this is bad news, because it means that the population has been growing way too rapidly. Generational Dynamics gives a very clear picture, on a country by country basis, where each country is going. For most countries, conditions are increasingly right for participation in a "clash of civilizations" world war.

The findings of Generational Dynamics are that every tribe, society, and nation goes through the same genocidal crisis war cycle. There is no known difference between democracies and dictatorships, republicanism and fascism, fiefdoms and monarchies, presidential systems and parliamentary systems, small tribes and international superpowers.

What then are the criteria for moral genocidal wars? For the most part, this is a political judgment, and so is beyond the scope of this book.

So we restrict ourselves here to simply listing some of the issues.

International law tells us that genocide is a war crime. And yet, Generational Dynamics tells us that every nation becomes genocidal during crisis wars. In fact, the growth of population faster than the food supply makes genocidal wars a requirement for survival.

In criminal law, there are various categories of guilt when one person kills another. There's "murder one," when you can prove premeditation, motive and opportunity. There's "self-defense," when it's kill or be killed. And there are other categories -- murder two, manslaughter, etc. -- in between those two extremes.

Well, can't any act of genocide be considered self-defense? Since there's not enough food for everyone, then it's only right for people of my nation, my race, my religion, my skin color or my ethnicity to try to exterminate people of other nations, races, religions, skin colors and ethnicities, since there's only enough food for us or them, but not both.

America actually has good legal defenses for almost all its wars. General Sherman's scorched earth march through Georgia in 1864 was justified because the South started the Civil War. The same reasoning applies to the genocidal firebombing of cities in World War II, and the use of nuclear weapons.

But is that enough of a legal defense to genocide? Is genocide more moral if the other side starts the war? How much genocide does the other side have to commit before you're allowed to commit genocide and still be moral?

Conversely, now that Generational Dynamics tells us that we're going to be entering a new genocidal world war, we can anticipate that our enemy is going to try to exterminate us. (Indeed, Islamist extremists have said they would try.) Doesn't that give us license to be genocidal even before the other side is?

Those are political problems, but the religious problems are even knottier.

According to beliefs in most religions, wars are the fault of human beings, and are certainly not God's fault.

But now we've shown that wars are caused by generational cycles and by the fact that population grows faster than the food supply, and that poverty mathematically MUST increase every year, until a crisis war breaks out to bring down the population again.

Now, if God is all-powerful, and God created the earth, it's clear he could have created an earth where the food supply and population grew at the same rate. Instead, he created a world in which the population grows substantially faster than the food supply. That's his fault.

That means that periodic wars are mathematically required. That's also his fault. Therefore, wars are God's fault, not humans' fault.

So if you're religious, then Generational Dynamics tells you that wars are God's fault. If you're not religious, then Generational Dynamics tells you that wars are part of Darwin's "survival of the fittest" paradigm. Either way, it's not human beings that are at fault for war. We're just doing what our DNA is telling us to do.