Dynamics

|

Generational Dynamics |

| Forecasting America's Destiny ... and the World's | |

| HOME WEB LOG COUNTRY WIKI COMMENT FORUM DOWNLOADS ABOUT | |

Investors have been getting measureably more risk-averse since October, with the result that nervousness is exceptionally high as Monday approaches.

Traders are calling Friday, the worst trading day in 3 years, a "blood bath," after the DJIA fell three out of last week's four trading days:

Date DJIA (Change)

-------------- ------ ---------

Tue 2006-01-17 10896.32 ( -0.58%)

Wed 2006-01-18 10854.86 ( -0.38%)

Thu 2006-01-19 10880.71 ( +0.24%)

Fri 2006-01-20 10667.39 ( -1.96%)

For the week, the DJIA fell 2.7%, the S&P lost 2%, and the Nasdaq ended 3% lower. All the gains of 2006 were wiped out this week.

Things were quite different last week, when giddy, giggling investors and analysts were popping champagne corks and celebrating the two days that the DJIA exceeded 11,000 for the first time since June, 2001.

According to one analyst commenting last week, it's about time. Hitting 11,000 merely meant the Dow was "catching up with the other averages," said Alexander Paris, economist and market analyst for Chicago-based Barrington Research. "It's just a matter of the market evening itself out," he said. "The Dow was the only average in 2005 that didn't go up."

A search on Google news revealed no quotes or opinions from Alexander Paris on this week's market activity.

Last week's giddiness also came through in an article that appeared in Time Magazine online:

The article says that "GDP growth is on track, inflation is tame, corporate earnings are good, dividends are up and values have become attractive," and quotes hedge fund mogul Leon Cooperman as saying that valuations [price/earnings ratios] "are reasonable."

However, a search on Google news revealed no quotes or opinions from Leon Cooperman on this week's earnings reports.

The psychological framework for investors and analysts was set early in the week when the Tokyo Stock Exchange's Nikkei index fell 6.22% in three days, resulting in worldwide shock waves. One analyst told the New York Times that, "This thing has taken on greed, panic and fear."

Actually, it's more than psychology, and Time Magazine's claim that "the fundamentals are good" is simply not true.

An AP analysis this weekend shows that we've been seeing "a recent streak of earnings disappointments." It adds, "That's created intense concern that other companies' fourth-quarter results will likewise fall short. The expectation of those disappointments fueled the selloff, with investors dumping stocks ahead of earnings reports in hopes of softening the blow."

This was fully to be expected, and there's worse to come.

Earnings have been exceptionally high for ten years by historical standards. Analysis shows that corporate earnings grow at an average of 11% per year, and that this has been true for close to a century. In fact, you can pick any 20-year period, and earnings have averaged 11% in that 20 year period. That means that earnings will average 11% during the 20-year period from 1995 to 2014.

But since 1995, corporate earnings have averaged 18% per year.

Now apparently a wide variety of investors, analysts and financial managers -- people who are really supposed to know better because it's their job to know better -- have become so giddy that they believe that the laws of nature have been revoked, just for them.

Apparently many airheads in the Wall Street and investment community believe that if earnings have been growing at 18% for the last ten years, then they'll continue to grow at 18% a year.

But that's not what's going to happen. The applicable principle is a mathematical term called "mean reversion": When the value of a variable stays above average for a long time, then it has to fall below average for just as long at time in order to maintain the historical average. In other words, the variable falls low enough so that the variable reverts to its historical "mean" or average.

Applying mean reversion to corporate earnings: The historical average growth is 11%; but growth since 1995 has been 18%; therefore, the average for the next ten years will be 4%, in order to revert the average to 11% for the entire period.

This reversion of earnings growth must happen, and might have begun at any time, and in fact I thought it might start happening in 2005. But earnings growth remained high in 2005.

Now, the first earnings forecasts for 2006 appear to indicate that mean reversion of earnings growth is finally starting to be felt. If next week's earnings reports show that to be the case, then the effect on the stock market and the economy is likely to be dramatic.

Long-time readers of this web site will recall that I wrote an article that appeared on August 11 of last year, I wrote about a "new mystery" involving the following graph:

|

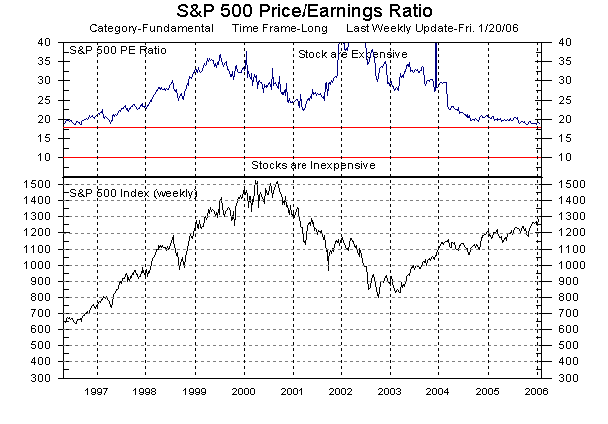

This graph showed the S&P 500 P/E ratio index for the period ending August 5, and it showed something very strange: The P/E ratio had remained constant at around 20 for almost a year.

In that article, I speculated that the airhead investors, analysts and financial managers on Wall Street were all making decisions based on exactly the same formula that they shared with one another over water coolers and on barstools. I speculated that the formula was based on something called the "Fed Model," a fallacious but widely used investment formula derived from a single paragraph buried deep in a 1997 Federal Reserve report. Since investors all used the same formula, the P/E ratios were remaining constant.

But something happened last September and October to cause investors to become more cautious.

As I wrote in October, investors had suddenly pushed the P/E ratio from 20 down to the 18-19 range, indicating that they were unwilling to pay as much for the stock of companies with the same earnings as before. Thus, they were unwilling to take as much risk as before.

Now, several months later, let's see how the graph as changed:

|

As you can see, the P/E ratio index has been steady since October, but at the lower 18-19 value. This indicates that the great mass of airhead investors and analysts had changed their formulas to reflect a desire to demand higher earnings for a given stock price. This is one way of measuring investors' "risk averseness"; if they're demanding greater earnings for a given stock price, then they're willing to take less risk, and they're becoming increasingly risk-averse.

Actually, if you look at the above graph, you'll see that there was a sharp fall in the P/E ratio index early in 2004, and that it's been falling steadily ever since.

What we're seeing is actually something that Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan warned us about last August. In a speech to central bankers,

We've been going through a "protracted period of low risk premiums," based on "abundant liquidity" resulting from low interest rates and a bubble investor mentality. But now we have "increase investor caution," or increased risk aversion. The result? "[H]istory has not dealt kindly with the aftermath of protracted periods of low risk premiums."

So, we're now in a climate of increasing risk-aversion. What happens in that climate if earnings start to fall?

The answer is that we'll begin to see "mean reversion" in its most vicious form, since mean reversion also applies to the P/E index itself. The long term average for the P/E index in the above graphs is around 14. It's been well above 14 for over ten years now, and in fact it's reached as high as the 60s for a while.

In order to return to the average of 14, it will have to compensate by falling well below 10. In fact, it's been down as low as 5 many times in the last century, so that wouldn't be so unusual.

But at a time when earnings are falling, a P/E ratio index of 5 means a DJIA even below the 3,000-4,000 range that I've been predicting on this web site since 2002.

If you'd like to see what happened in the Great Depression, take a look at the analysis of the "Great Depression and the Dow Jones Industrial Average," that I just posted. What you'll see there is how "mean reversion" works at its most vicious: The DJIA actually fell 90% between 1929 and 1932. If the same thing happens this time, and it might, then the market will fall to Dow 1100 by 2009.

The only remaining question is when this precipitous fall will begin. While it's impossible to predict when a panic will occur, we've described a number of current factors that indicate that the time is right, right now, for a panic.

The things to watch for are continued bad earnings news and increased

volatility. Both of these occurred last week. If they continue to

occur, they'll indicate that a panic may occur very soon.

(22-Jan-06)

Permanent Link

Receive daily World View columns by e-mail

Donate to Generational Dynamics via PayPal

Web Log Summary - 2016

Web Log Summary - 2015

Web Log Summary - 2014

Web Log Summary - 2013

Web Log Summary - 2012

Web Log Summary - 2011

Web Log Summary - 2010

Web Log Summary - 2009

Web Log Summary - 2008

Web Log Summary - 2007

Web Log Summary - 2006

Web Log Summary - 2005

Web Log Summary - 2004

Web Log - December, 2016

Web Log - November, 2016

Web Log - October, 2016

Web Log - September, 2016

Web Log - August, 2016

Web Log - July, 2016

Web Log - June, 2016

Web Log - May, 2016

Web Log - April, 2016

Web Log - March, 2016

Web Log - February, 2016

Web Log - January, 2016

Web Log - December, 2015

Web Log - November, 2015

Web Log - October, 2015

Web Log - September, 2015

Web Log - August, 2015

Web Log - July, 2015

Web Log - June, 2015

Web Log - May, 2015

Web Log - April, 2015

Web Log - March, 2015

Web Log - February, 2015

Web Log - January, 2015

Web Log - December, 2014

Web Log - November, 2014

Web Log - October, 2014

Web Log - September, 2014

Web Log - August, 2014

Web Log - July, 2014

Web Log - June, 2014

Web Log - May, 2014

Web Log - April, 2014

Web Log - March, 2014

Web Log - February, 2014

Web Log - January, 2014

Web Log - December, 2013

Web Log - November, 2013

Web Log - October, 2013

Web Log - September, 2013

Web Log - August, 2013

Web Log - July, 2013

Web Log - June, 2013

Web Log - May, 2013

Web Log - April, 2013

Web Log - March, 2013

Web Log - February, 2013

Web Log - January, 2013

Web Log - December, 2012

Web Log - November, 2012

Web Log - October, 2012

Web Log - September, 2012

Web Log - August, 2012

Web Log - July, 2012

Web Log - June, 2012

Web Log - May, 2012

Web Log - April, 2012

Web Log - March, 2012

Web Log - February, 2012

Web Log - January, 2012

Web Log - December, 2011

Web Log - November, 2011

Web Log - October, 2011

Web Log - September, 2011

Web Log - August, 2011

Web Log - July, 2011

Web Log - June, 2011

Web Log - May, 2011

Web Log - April, 2011

Web Log - March, 2011

Web Log - February, 2011

Web Log - January, 2011

Web Log - December, 2010

Web Log - November, 2010

Web Log - October, 2010

Web Log - September, 2010

Web Log - August, 2010

Web Log - July, 2010

Web Log - June, 2010

Web Log - May, 2010

Web Log - April, 2010

Web Log - March, 2010

Web Log - February, 2010

Web Log - January, 2010

Web Log - December, 2009

Web Log - November, 2009

Web Log - October, 2009

Web Log - September, 2009

Web Log - August, 2009

Web Log - July, 2009

Web Log - June, 2009

Web Log - May, 2009

Web Log - April, 2009

Web Log - March, 2009

Web Log - February, 2009

Web Log - January, 2009

Web Log - December, 2008

Web Log - November, 2008

Web Log - October, 2008

Web Log - September, 2008

Web Log - August, 2008

Web Log - July, 2008

Web Log - June, 2008

Web Log - May, 2008

Web Log - April, 2008

Web Log - March, 2008

Web Log - February, 2008

Web Log - January, 2008

Web Log - December, 2007

Web Log - November, 2007

Web Log - October, 2007

Web Log - September, 2007

Web Log - August, 2007

Web Log - July, 2007

Web Log - June, 2007

Web Log - May, 2007

Web Log - April, 2007

Web Log - March, 2007

Web Log - February, 2007

Web Log - January, 2007

Web Log - December, 2006

Web Log - November, 2006

Web Log - October, 2006

Web Log - September, 2006

Web Log - August, 2006

Web Log - July, 2006

Web Log - June, 2006

Web Log - May, 2006

Web Log - April, 2006

Web Log - March, 2006

Web Log - February, 2006

Web Log - January, 2006

Web Log - December, 2005

Web Log - November, 2005

Web Log - October, 2005

Web Log - September, 2005

Web Log - August, 2005

Web Log - July, 2005

Web Log - June, 2005

Web Log - May, 2005

Web Log - April, 2005

Web Log - March, 2005

Web Log - February, 2005

Web Log - January, 2005

Web Log - December, 2004

Web Log - November, 2004

Web Log - October, 2004

Web Log - September, 2004

Web Log - August, 2004

Web Log - July, 2004

Web Log - June, 2004