Dynamics

|

Generational Dynamics |

| Forecasting America's Destiny ... and the World's | |

| HOME WEB LOG COUNTRY WIKI COMMENT FORUM DOWNLOADS ABOUT | |

The nominal deadline: 7 pm ET Sunday, when the Asian stock markets open.

In March, it was Bear Stearns. Last weekend, it was Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

This weekend it's Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc.

|

As we wrote several days ago, the investment bank Lehman Brothers appeared close to collapse. Not only that, but no one on Wall Street or in Washington had any idea at all what's coming next.

There's a growing sense of panic on Wall Street and Washington, as the financial system that's served since the Great Depression appears to be crumbling. Last year I compared the financial system to a huge, bloated mansion, where different gables and rooms and other portions keep falling off into the ravine below. Central bankers run around the mansion with hammers and nails and glue, but pieces keep falling off, and the fear grows that the entire mansion will collapse into the ravine.

According to an article in Friday's WSJ:

With the share prices of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc., Merrill Lynch & Co. and other financial firms on a roller coaster, the crisis could be entering a critical stage.

The Federal Reserve has already slashed interest rates to counteract a deepening credit freeze and instituted its broadest expansion of lending facilities since the Great Depression to keep financial markets functioning. Over the weekend, the nation's two main mortgage finance firms -- Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac -- were placed under government control.

Federal officials and market players are struggling with the same issues: Why haven't the steps taken so far calmed the system? What can policy makers do next? Should the U.S. government let a big institution fail rather than stage another potentially costly bailout?"

Washington and Wall Street officials are getting desperate. On Friday evening, the heads of major Wall Street firms were summoned to a meeting by government officials from the Fed and Treasury Dept. They said, in no uncertain terms, that Lehman must be rescued, through sale of the company or some kind of orderly liquidation.

According to a NY Times article:

Mr. Geithner told the participants that an industry solution was needed, no matter what, and that it was not about any individual bank, according to two people briefed on the meeting but who did not attend. They said he told them that if the industry failed to solve the problem their individual banks might be next. ...

Policy makers fear its losses could ripple through the financial industry at a time when banks and securities firms are trying to overcome $500 billion in write-downs."

What's interesting is that game of "chicken" is being played:

Bank of America and two British firms, Barclays and HSBC, have expressed interest in bidding for Lehman Brothers, according to people briefed on the situation. But they have indicated that their bids are contingent upon receiving support from the government, just as it did with the rescues of Bear Stearns, and the government-sponsored agencies, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

But Mr. Paulson and Mr. Geithner made it clear to the company, its potential suitors and to the meeting participants on Friday that the government has no plans to put taxpayer money on the line. The government is deeply worried that its actions have created a moral hazard and the Federal Reserve does not want to reach deeper into its coffers. Instead, Mr. Paulson and Mr. Geithner insist that Wall Street needs to come up with an industry solution to try to stabilize Lehman Brothers and calm the markets.

Still, some of the other Wall Street banks, facing billions of dollars in losses themselves, have resisted this approach. They argue that Lehman Brothers overreached and brought its current troubles on itself. If there are no bidders for Lehman Brothers, these banks say they can collect their collateral and liquidate the troubled firm’s assets. In this high-stake game, they may also be trying to call the government’s bluff, knowing that if push came to shove, it would provide financial support."

The tension and anxiety are palpable. I heard pundits describe the situation as "scary."

The banks are demanding that the government backstop any deal, just as the government has already backstopped the deals with Bear Stearns, Fannie and Freddie.

The government is saying that this kind of backstopping has got to stop because of "moral hazard." In this view, the problems have been getting worse because the previous backstopping has encourage more bad behavior among banks, who assume that they'll be bailed out.

Since nothing that either the banks or the government have tried is working, they're essentially blaming each other for causing the problems, and "struggling to understand" why nothing they do has worked.

Maybe now is a good time to re-post the graph that I've posted many times before.

As I've been saying hundreds of times since 2002, the stock market is overpriced by a factor of more than 200%, as I described in "How to compute the 'real value' of the stock market," indicating that we're entering a new 1930s style Great Depression. In 2002 I had no idea what scenario we would follow to reach that point, but the end result has always been certain with 100% probability.

Here's the first graph that I used in that article:

|

The historic average of the P/E1 (price divided by one-year trailing earnings) is about 14. From 1995 to the present, it's averaged around 25, creating a huge bubble. By the Law of Mean Reversion, the price/earnings ratio will fall well below 10 for a dozen years or so. You can see that it's poised to fall quickly in the near future, leading to a stock market crash.

So when I see a sentence like, "Officials and market players are struggling to understand why the steps taken so far haven't calmed the system," I come away amazed. The above graph, and the article that it's from, are not based on some fantastical computational algorithms (like the ones that "financial engineers" used that got us into the structured finance mess.) Nor is the above based on some specific political ideology or some specific economics ideology (like the "Austrian school" or "Keynesian economics" or "monetarist economics."

This is a simple price/earnings computation (also called "valuations") that Wall Street uses all the time. And anyone can see, just by glancing at it, what's coming.

So why are these people "struggling to understand"? Are they total morons?

There's a principle, in ethics and in law, that public figures who might influence investors MUST tell the truth. Depending on how you interpret this, public figures might include government officials, corporate CEOs, financial journalists, financial analysts, and so forth.

Unfortunately, with the breakdown in ethics that's occurred in the last ten years, as Boomers and Gen-Xers have taken senior management positions everywhere, the forces of political correctness have decreed that certain lies are "good," and certain lies are "bad."

An example of a "bad lie" was pointed out by the SEC in July: "False rumors can lead to a loss of confidence in our markets. ... During the week of March 10, 2008, rumors spread about liquidity problems at Bear Stearns, which eroded investor confidence in the firm, ... and a crisis of confidence occurred late in the week."

And so, if someone anonymously posts a rumor -- and the rumor later turns out to be false -- and the rumor was negative in nature, then it's a "bad lie." Of course, the rumors they're talking about turned out to be true.

On the other hand, if a corporate CEO or a government official says something POSITIVE, rather than negative, then the rumor is a "good lie," even if the rumor turns out to be false.

For some reason, a negative rumor posted anonymously by someone deserves the harshest condemnation, even though only the stupidest investor would ever believe an anonymous rumor. It's a "bad lie," even if it turns out to be the truth.

But a positive rumor, stated openly by public officials is a "good lie," even though it causes thousands of investors to lose a great deal of money.

That's how twisted everything is today.

And so, for example, several months ago, government officials told the public that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were sound, and that the public should invest in Fannie and Freddie stock as a good, solid, long-term investment.

Unfortunately, those shares were wiped out last weekend, when Fannie and Freddie were effectively nationalized.

So you might say, "Well, six months ago these government officials didn't know what would happen. They weren't lying; they were simply mistaken."

Ahhh, but the ethics are MUCH more complicated than that.

Because the same government officials who encouraged investors to buy stock shares also were responsible for structuring the nationalization effort in such a way that those stock shares would be wiped out.

The reasoning is simple: People who buy stock shares own a part of the company. They make money if the company does well, and they lose money if the company is does poorly, or is nationalized.

This is the concept of "moral hazard" that everyone talks about. If the government bails out the stock holders after bad behavior by the company, then the government is encouraging more bad behavior.

In other words, if I sell you my car, telling you it's in great shape, and you pay me, but then I smash it up as I'm delivering the car to you, who's responsible for the smashup? You? Me? The car?

I think you would say that I owe you a refund, and it would make no difference if I told you that I wasn't lying when I sold it to you.

At any rate, stock fund manager Bill Miller of Legg Mason Value Trust purchased 79 million shares of Fannie and Freddie, at prices ranging from $5 to $50 per share. By Tuesday, shares were selling at 88 cents each, and so investors in this mutual fund lost some 90% of their investments.

By contrast, bond fund manager Bill Gross of Pimco Total Return invested almost $100 billion in Fannie and Freddie bonds. The nationalization was structured so that bond holders would be protected, and so investors in his mutual fund gained some 20% on their investments.

Can anyone tell me why the deal was structured so that one mutual fund was wiped out, while the other made huge amounts of money? Why is one "moral hazard," and the other isn't?

Was Bill Miller just being naïve when he believed government officials who encouraged investors to purchase Fannie and Freddie stock shares? Or was he swindled when those same government officials actively reneged on their statements and pulled the plug on stock shares?

So now we hear that these same people are "struggling to understand why the steps taken so far haven't calmed the system." I said that these people must be morons, but there's more.

These people say any crap that they want, with no regard for the truth. The lie to themselves, to each other, and to the public.

And as I discussed in "Brilliant Nobel Prize winners in Economics blame credit bubble on 'the news'," with respect to Joseph Stiglitz, 2001 Nobel Prize Winner in Economics, not only do these guys say any crap that comes into their head, not only do they lie to themselves, each other and the public, they also think that all the rest of us are idiots. Because if a Nobel Prize winner in economics can say such incredibly stupid and inane things and get a Nobel prize, then obviously his assessment of people as idiots must be correct.

As I've said many times on this web site, the stench of corruption and fraud is beyond belief, and it constantly sickens me and infuriates me. These people on Wall Street and in Washington and in university economics departments are so depraved that it's almost impossible not to throw up. See: "'Operation Malicious Mortgage' indicts 406 people including Bear Stearns execs."

The real "moral hazard" is listening to anything that these people say.

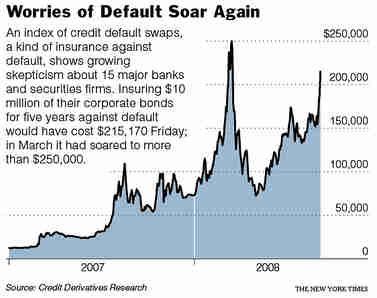

Something happened last weekend that's never happened before: The nationalization of Fannie and Freddie caused a "CDS event" involving trillions of dollars of credit default swaps.

Recall that a CDS is a contract between two people, that acts like an insurance policy. The insurance pays off if the company named in the CDS (usually a completely unrelated third company) defaults on its bonds.

If you have fire insurance on your home, then a "fire insurance event" that triggers payment of the insurance is a fire in your home.

If you have a CDS for some company, then a "CDS event" triggers payment of the insurance.

Well, the nationalization of Fannie and Freddie caused a "CDS event" linked to Fannie's and Freddie's bonds. It potentially could trigger trillions of dollars in payments.

This is ironic, of course, because it's the stock holders that lost 95% of their investment. The nationalization protected the bondholders with government guarantees, so bond holders actually made money. So although trillions of dollars in CDS payments might be theoretically possible, in actual practice the payoffs will be very small, or nonexistent.

So there you go. The reason that the nationalization was structured to protect bondholders is that they didn't want to trigger large CDS payments. All that stuff about "moral hazard" was just more crap. Moral hazard had nothing to do with it.

Question: How can you tell whether a government official, or financial executive, or financial journalist or financial analyst or financial commentator is lying? Answer: Watch to see whether his mouth is moving.

(For those interested in the math behind the creation of CDOs from CDSs, see "A primer on financial engineering and structured finance." For a discussion of credit default swap (CDS) counterparty risk, see "Brilliant Nobel Prize winners in Economics blame credit bubble on 'the news.'")

Speculators are beginning to see a pattern here:

One way to tell whether the market thinks that a company is close to default is to watch the cost of credit default swaps (CDSs) that insure the company's bonds.

Take American International Group (AIG) Inc., the largest U.S. insurer, for example.

In May, I wrote about AIG's sad story. Last December, they had put on a spectacle bragging about how clever they had been, avoiding the writedown disasters that had struck Citibank, Merrill Lynch, and other companies. In May the announced massive first quarter writedowns, and were silent about whether there were more to come.

AIG has been suffering further losses, but Rodney Clark of S&P's ratings agency says, "AIG has sufficient capital and liquidity to meet its policy obligations and potential collateral requirements, which are significantly greater than the expected cash losses on the mortgage-related assets." Given the track record of these agencies, this statement may be anywhere from a near-truth to a total lie. History provides no reason to believe it since, if it's a lie, it's a "good lie."

|

Still, the market apparently doesn't believe S&P. (I wonder why?) We know this because the price of credit default swaps on AIG debt has ballooned.

On Thursday, you could buy CDS insurance protection on $10 million of AIG bonds for $668,000 per year. On Friday, it had shot up to $764,000 per year. For comparison, "normal" rates are about $100,000 per year.

Moving into the realm of banks, Washington Mutual (WaMu) Inc. has also seen its CDS prices balloon. To protect $10 million of WaMu bonds against default for 5 years, investors must pay about $4.15 million up front, and $500,000 annually, to protect $10 million of WaMu bonds against default for five years.

AIG and WaMu are now going through the same kind of shelling that brought down Bear Stearns and Lehman. Whether these two companies can survive much longer remains to be seen.

The Generational Dynamics forecasting methodology has, in summary, two components: The first is a long term trend component that tells you where you're going to end up, but doesn't tell you how you'll get there, or how long it will take. The second is the collection of short-term daily events that lead you to the final result. You use the long-term trend component to guide your interpretation of the short-term events. The result is a forecast with a very high probability of success (usually 80-90% or more), in a time frame of a few weeks or months.

Every analyst and pundit tries to make forecasts based on short-term events. Their forecasts have only a 50-50 chance of being right, because basically they're guesses. Generational Dynamics predictions, based on analyses of short-term events, have a very high probability of being right because the long-term generational trend component provides guidance.

|

(See "List of major Generational Dynamics predictions" for more information about these predictions.)

In this case, the long-term generational trend, which I first started talking about in 2002, was that the stock market was overpriced by a factor of 200%+ and that we would enter a new 1930s style Great Depression, probably in the 2006-2007 time frame.

In August, 2007, I wrote, "The nightmare is finally beginning." Generational Dynamics is based on changes in attitudes and behaviors of great masses of people, entire generations of people. I observed that the "credit crunch" had had a massive effect on the attitudes and behaviors of investors, and so the long-term prediction was coming to pass. I expected to see that within weeks or a few months.

Now, just over a year later, we see the daily events quickening. The short-term trends and events are matching up more closely to the long-term trend prediction. Here's what's happened since August, 2007:

Here's how a NY Times article describes it:

So far, they have all been wrong.

Since the financial crisis first hit in August 2007, markets — and the financial industry — have gone through a series of swoons, each more dizzying than the last. Last week, the crisis reached a new pitch, as Lehman Brothers, the fourth-largest United States investment bank, struggled to avoid joining Bear Stearns on the trash heap, and Washington Mutual, the largest savings and loan, saw its shares briefly fall below $2.

Now even Wall Street’s professional optimists have given up predicting exactly when their industry might stabilize. One senior executive at a top investment bank, speaking anonymously so he could speak freely, recently observed that the crisis was entering its “19th inning,” with no ending in sight."

If a story like this had appeared a year ago, the author would have been called crazy. Today, these attitudes are the norm.

However, it's important to understand that these people, these experts, haven't yet come to the point where they realize what's going to happen. These people are "struggling to understand why the steps taken so far haven't calmed the system" because they don't really understand what's going on, or what a deflationary spiral really means.

What's most significant is the learning curve of Fed chairman Ben Bernanke himself. I've written several times about Ben Bernanke and his Great Historic Experiment, and his belief that the 1930s Great Depression could have been avoided if the Fed had simply lowered interest rates sooner.

Ben Bernanke is considered the world's leading expert on the Great Depression, and his views that the 1930s Depression could have been easily avoided have dominated university macroeconomics. Now the conclusion of his life's work has been proven wrong, as one "fix" after another has led only to a worse situation.

Here's an interesting excerpt from the same NY Times article:

“The restraint in the credit markets will last quite some time,” Dr. Sohn said. In the mortgage business, which saw the worst excesses, loan practices may remain stricter for at least a decade, he said. The results will be both positive and negative, he said."

Sohn reflects a fairly standard and widely held view: That the credit crunch will only last another year or so, and then it will take 10 years to get over it. This of course is a change from even a few months ago, when it was widely believed that the credit crunch would be over by now, and the economy would be in bubble mode again by the end of this year.

But this is another attitude trend -- the length of time that mainstream economists expect the economy to be affected by this. In the last year, this estimate has gone from a few weeks to a few months to ten years. At some point, they'll understand that this event will affect the entire lifetimes of the survivors -- just as the 1930s Great Depression did.

I've estimated that the probability of a major financial crisis (generational stock market panic and

crash) in any given week from now on is about 3%. The probability of

a crisis some time in the next 52 weeks is 75%, according to this

estimate.

(13-Sep-2008)

Permanent Link

Receive daily World View columns by e-mail

Donate to Generational Dynamics via PayPal

Web Log Summary - 2016

Web Log Summary - 2015

Web Log Summary - 2014

Web Log Summary - 2013

Web Log Summary - 2012

Web Log Summary - 2011

Web Log Summary - 2010

Web Log Summary - 2009

Web Log Summary - 2008

Web Log Summary - 2007

Web Log Summary - 2006

Web Log Summary - 2005

Web Log Summary - 2004

Web Log - December, 2016

Web Log - November, 2016

Web Log - October, 2016

Web Log - September, 2016

Web Log - August, 2016

Web Log - July, 2016

Web Log - June, 2016

Web Log - May, 2016

Web Log - April, 2016

Web Log - March, 2016

Web Log - February, 2016

Web Log - January, 2016

Web Log - December, 2015

Web Log - November, 2015

Web Log - October, 2015

Web Log - September, 2015

Web Log - August, 2015

Web Log - July, 2015

Web Log - June, 2015

Web Log - May, 2015

Web Log - April, 2015

Web Log - March, 2015

Web Log - February, 2015

Web Log - January, 2015

Web Log - December, 2014

Web Log - November, 2014

Web Log - October, 2014

Web Log - September, 2014

Web Log - August, 2014

Web Log - July, 2014

Web Log - June, 2014

Web Log - May, 2014

Web Log - April, 2014

Web Log - March, 2014

Web Log - February, 2014

Web Log - January, 2014

Web Log - December, 2013

Web Log - November, 2013

Web Log - October, 2013

Web Log - September, 2013

Web Log - August, 2013

Web Log - July, 2013

Web Log - June, 2013

Web Log - May, 2013

Web Log - April, 2013

Web Log - March, 2013

Web Log - February, 2013

Web Log - January, 2013

Web Log - December, 2012

Web Log - November, 2012

Web Log - October, 2012

Web Log - September, 2012

Web Log - August, 2012

Web Log - July, 2012

Web Log - June, 2012

Web Log - May, 2012

Web Log - April, 2012

Web Log - March, 2012

Web Log - February, 2012

Web Log - January, 2012

Web Log - December, 2011

Web Log - November, 2011

Web Log - October, 2011

Web Log - September, 2011

Web Log - August, 2011

Web Log - July, 2011

Web Log - June, 2011

Web Log - May, 2011

Web Log - April, 2011

Web Log - March, 2011

Web Log - February, 2011

Web Log - January, 2011

Web Log - December, 2010

Web Log - November, 2010

Web Log - October, 2010

Web Log - September, 2010

Web Log - August, 2010

Web Log - July, 2010

Web Log - June, 2010

Web Log - May, 2010

Web Log - April, 2010

Web Log - March, 2010

Web Log - February, 2010

Web Log - January, 2010

Web Log - December, 2009

Web Log - November, 2009

Web Log - October, 2009

Web Log - September, 2009

Web Log - August, 2009

Web Log - July, 2009

Web Log - June, 2009

Web Log - May, 2009

Web Log - April, 2009

Web Log - March, 2009

Web Log - February, 2009

Web Log - January, 2009

Web Log - December, 2008

Web Log - November, 2008

Web Log - October, 2008

Web Log - September, 2008

Web Log - August, 2008

Web Log - July, 2008

Web Log - June, 2008

Web Log - May, 2008

Web Log - April, 2008

Web Log - March, 2008

Web Log - February, 2008

Web Log - January, 2008

Web Log - December, 2007

Web Log - November, 2007

Web Log - October, 2007

Web Log - September, 2007

Web Log - August, 2007

Web Log - July, 2007

Web Log - June, 2007

Web Log - May, 2007

Web Log - April, 2007

Web Log - March, 2007

Web Log - February, 2007

Web Log - January, 2007

Web Log - December, 2006

Web Log - November, 2006

Web Log - October, 2006

Web Log - September, 2006

Web Log - August, 2006

Web Log - July, 2006

Web Log - June, 2006

Web Log - May, 2006

Web Log - April, 2006

Web Log - March, 2006

Web Log - February, 2006

Web Log - January, 2006

Web Log - December, 2005

Web Log - November, 2005

Web Log - October, 2005

Web Log - September, 2005

Web Log - August, 2005

Web Log - July, 2005

Web Log - June, 2005

Web Log - May, 2005

Web Log - April, 2005

Web Log - March, 2005

Web Log - February, 2005

Web Log - January, 2005

Web Log - December, 2004

Web Log - November, 2004

Web Log - October, 2004

Web Log - September, 2004

Web Log - August, 2004

Web Log - July, 2004

Web Log - June, 2004