Dynamics

|

Generational Dynamics |

| Forecasting America's Destiny ... and the World's | |

| HOME WEB LOG COUNTRY WIKI COMMENT FORUM DOWNLOADS ABOUT | |

Several readers have notified me about this event that has Wall Street buzzing. One reader even suggested that I might be the mysterious investor! Very droll.

My first reaction on reading this story was that, whoever the investor is, he might have seen my web site or, more likely, performed the same computation that I did.

Understanding deflation: Why there's less money in the world today than a month ago.:

As the markets continue to fall, the Fed is increasingly in a big bind....

(10-Sep-07)

Alan Greenspan predicts the panic and crash of 2007:

He's said this kind of thing before, but this time it's resonating....

(08-Sep-07)

Bernanke's historic experiment takes center stage:

An assessment of where we are and where we're going....

(27-Aug-07)

How to compute the "real value" of the stock market. :

And some additional speculations about stock market crashes.

(20-Aug-2007)

Ben Bernanke's Great Historic Experiment:

Bernanke doesn't believe that bubbles exist. His Fed policy will now test his core beliefs....

(18-Aug-07)

Redemptions of money market funds now fully in doubt:

Wednesday is the deadline for 3Q redemption of many hedge fund shares....

(15-Aug-07)

Alan Greenspan defends his Fed policies, as people blame him for the subprime crisis:

Greenspan never ceases to amaze, and he did so again on Monday....

(8-Aug-07)

Nouriel Roubini says: "Worry about systemic risk." Whoo hoo!:

His arguments show what's wrong with mainstream macroeconomics....

(6-Aug-07)

Robert Shiller compares stock market to 1929:

He says the recent fall was caused by "market psychology," but is puzzled why....

(20-Mar-07)

A conundrum: How increases in 'risk aversion' lead to higher stock prices:

Maybe because the global financial markets are increasingly "accident-prone."...

(12-Mar-07)

Pundits are suddenly talking about (gasp!) "risk aversion":

Fearing full-scale panic in the mortgage loan marketplace,...

(6-Mar-07)

Alan Greenspan blames the housing bubble on the fall of the Berlin Wall:

Meanwhile, the stock market keeps skyrocketing and appears unstoppable to many investors....

(25-Oct-06)

System Dynamics and the Failure of Macroeconomics Theory :

Mainstream macroeconomic theory, invented by Maynard Keynes in the 1930s, has failed to predict or explain anything that's happened since the bubble started, including the bubble itself. We need a new "Dynamic Macroeconomics" theory.

(25-Oct-2006)

Alan Greenspan gives another harsh doom and gloom speech:

Saying that "the consequences for the U.S. economy of doing nothing could be severe,"...

(4-Dec-05)

Ben S. Bernanke: The man without agony :

Bernanke and Greenspan are as different as night and day, despite what the pundits say.

(29-Oct-2005)

Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan says that the deficit is out of control:

France's Finance Minister Thierry Breton quoted Greenspan...

(25-Sep-05)

Fed Governor Ben Bernanke blames America's sky-high public debt on other nations:

I'm normally wary of applying specific generational archetypes to individuals, but Bernanke is acting like a Baby Boomer....

(14-Mar-05)

Greenspan's testimony further repudiates his earlier stock bubble reasoning:

The Fed Chairman has now completely reversed his previous position on the stock market bubble...

(17-Feb-05)

Alan Greenspan warns that global economic dangers are without historical precedent :

In a speech on Friday, Greenspan buried a major change of position in a speech admitting that his assumptions about the economy for the last decade were wrong.

(6-Feb-2005)

| ||

I arrived at the September 21 date by speculating that the stock market, following its peak on July 19, would follow the same path that it followed after its peak in 1929. This is purely speculative, but it's easy enough for other people to reach the same conclusion.

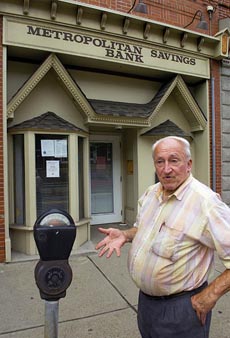

The news broke on August 21 that someone was making option bets that the S&P index would fall at least 35-40% by September 21. Since that time, speculation has been wild about what's going on. This mysterious person could lose $700-900 million if the market does not fall, but coul make about $2 billion if the market does fall far enough.

So we're talking about real money here. This isn't some flamboyant speculator who wants to impress his girlfriend. This is some major institution that's making a very serious and very huge bet.

There are a variety of explanations, ranging from relatively harmless to a sign of imminent war. Let's take a look at some of them:

There's a lot of concern these days that the market is due for a major correction, mainly because it's been so long since the last major correction. Even among those who believe that these times are perfectly normal, there is an expectation of SOME kind of correction, since an occasional correction IS perfectly normal.

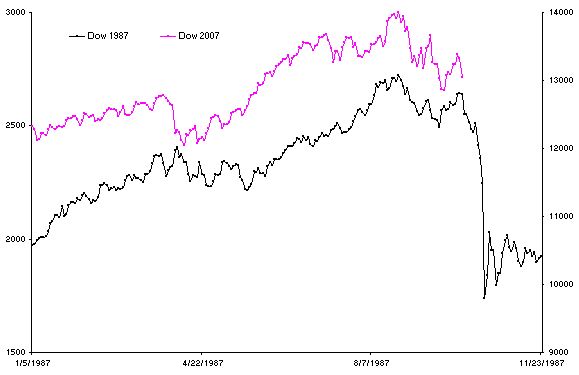

However, there really are a lot of people expecting a serious panic these days. One web site reader has just sent me his friend's graph comparing today's stock market with the 1987 stock market panic:

|

The Panic of 1987 was a false panic, since the market was underpriced at the time, so recovery was fairly rapid. (The market today is overpriced by a factor of about 250%, same as in 1929.)

Still, it was a panic, and the market that year followed a pattern similar to this year's pattern.

From the point of view of Generational Dynamics, the panic of 1987 was not a generational panic. If you go back through history, there are of course many small or regional recessions. But since the 1600s there have been only five major international financial crises: the 1637 Tulipomania bubble, the South Sea bubble of the 1710s-20s, the bankruptcy of the French monarchy in the 1789, the Panic of 1857, and the 1929 Wall Street crash. We're now overdue for the next one, and it might be close.

Addendum. For those interested in more details, the following is last night's options listings on http://finance.yahoo.com/q/op?s=SPY . The listing is for SPY, corresponding to the S&P 500. Notice the appearance of numerous twelve "10,000"s in the volume column. The mysterious investor has "bet" on almost every strike price from 60 to 95, which correspond to S&P 500 indexes of 600 to 950, respectively. These options are worthless unless the S&P 500 index, currently at 1460, falls into or below the 600-950 range by September 21. Also, a volume figure of 10,000 refers to 10,000 contracts of 100 shares each, or 1,000,000 shares. Since this was done for 12 different strike prices, the "bet" corresponds to 12,000,000 shares. (Paragraph added 31-Aug)

|

(31-Aug-07)

Permanent Link

Receive daily World View columns by e-mail

Donate to Generational Dynamics via PayPal

Returning to anxious, panicky behavior for the first time in ten days, nervous investors drove the Dow down 280 points, or 2.1%. The Nasdaq fell 2.37%.

The market opened down slightly, fell sharply at 10:30 am when the "consumer confidence" numbers were released, and then fell even more sharply at 2 pm, when the Fed published the minutes of its August 7 policy meeting.

|

At 10 am, a survey firm known as The Conference Board released the results of its monthly survey measuring consumer confidence. It had surged in July, and now fell sharply in August.

The Consumer Confidence Index is really no more significant than pop psychology, but it was enough to frighten investors into driving down the market almost 100 points.

Then, at 2 pm, the Federal Reserve released the minutes of the August 7 meeting that determines future interest rate policy. Apparently it's the following paragraph that spooked investors:

In other words, the August 7 minutes (from three weeks ago) say that the Fed believes that inflation is likely to continue, which means that they don't intend to lower the Fed Funds Rate from 5.25%.

Investors and journalists had been hopin' and prayin' that the Fed would reduce interest rates. Recall that it was just about three weeks ago that CNBC's Jim Cramer became hysterical, ranting that the Fed had to reduce interest rates by a full point (to 4.25%) or millions of people would lose their homes.

So this was the second event that spooked investors on Tuesday. The market started falling rapidly, especially in the last hour of trading (3-4 pm), resulting in a total fall of Dow 280 points for the day.

When I wrote, on August 17, that "The nightmare is finally beginning," I explained that what was important was not the ups and downs in the stock market, but the attitudes and behaviors of large groups of people, in this case, large groups of investors.

Some kind of tipping point was passed on July 23, a day of high volatility that followed the July 19 stock market peak. Up to that point, bad news made the stock market contine to rise. Since then, bad news is causing the market to make sharp falls.

On that day, Ben Bernanke's Fed lowered the discount rate, a move that had very little real effect, and was mostly symbolic. Still, it seemed to relieve the anxiety and panic that investors were experiencing.

Tuesday was the first day since then that the anxiety seemed to be returning.

Because of this change in behavior, I believe that a major stock market panic and crash is coming in a matter of weeks. The only thing that can stop this from happening is a reversal of the recent change in behavior, so investors become giddy, giggly and bubbly again, as they were until July 19. I consider such a reversal to be almost impossible, and since the stock market is overvalued by a factor of about 250%, so when investors change from risk-seeking to risk-averse, a slide will continue.

We're conducting a little real-time experiment, comparing the 1929 and 2007 markets, following the respective market peaks. Let's bring the comparison up to date.

This data is taken from my Dow Jones historical page. On September 3, 1929, the market peaked at Dow 381.17. By November 15, it had fallen 40% to 228.73. This year (so far), the market peaked on July 19 at 14000.

This comparison is purely speculative, but here's an update of that table:

1929 % of peak (381.17)

-------------------------

Tue 09-03 ( +0.22%) 100% 2007 % of peak (14000)

Wed 09-04 ( -0.41%) 99% ------------------------

Thu 09-05 ( -2.59%) 97% Thu 07-19 ( +0.59%) 100%

Fri 09-06 ( +1.76%) 98% Fri 07-20 ( -1.07%) 98%

------------------------ ------------------------

Mon 09-09 ( -0.36%) 98% Mon 07-23 ( +0.67%) 99%

Tue 09-10 ( -2.04%) 96% Tue 07-24 ( -1.62%) 97%

Wed 09-11 ( +0.99%) 97% Wed 07-25 ( +0.50%) 98%

Thu 09-12 ( -1.23%) 96% Thu 07-26 ( -2.26%) 96%

Fri 09-13 ( +0.14%) 96% Fri 07-27 ( -1.54%) 94%

------------------------ ------------------------

Mon 09-16 ( +1.51%) 97% Mon 07-30 ( +0.70%) 95%

Tue 09-17 ( -1.04%) 96% Tue 07-31 ( -1.10%) 94%

Wed 09-18 ( +0.65%) 97% Wed 08-01 ( +1.14%) 95%

Thu 09-19 ( -0.25%) 97% Thu 08-02 ( +0.76%) 96%

Fri 09-20 ( -2.14%) 94% Fri 08-03 ( -2.09%) 94%

------------------------ ------------------------

Mon 09-23 ( -0.84%) 94% Mon 08-06 ( +2.18%) 96%

Tue 09-24 ( -1.78%) 92% Tue 08-07 ( +0.26%) 96%

Wed 09-25 ( -0.01%) 92% Wed 08-08 ( +1.14%) 97%

Thu 09-26 ( +0.96%) 93% Thu 08-09 ( -2.83%) 94%

Fri 09-27 ( -3.11%) 90% Fri 08-10 ( -0.23%) 94%

------------------------ ------------------------

Mon 09-30 ( -0.41%) 90% Mon 08-13 ( -0.02%) 94%

Tue 10-01 ( -0.26%) 89% Tue 08-14 ( -1.57%) 93%

Wed 10-02 ( +0.56%) 90% Wed 08-15 ( -1.29%) 91%

Thu 10-03 ( -4.22%) 86% Thu 08-16 ( -0.12%) 91%

Fri 10-04 ( -1.45%) 85% Fri 08-17 ( +1.82%) 93%

------------------------ ------------------------

Mon 10-07 ( +6.32%) 90% Mon 08-20 ( +0.32%) 93%

Tue 10-08 ( -0.21%) 90% Tue 08-21 ( -0.23%) 93%

Wed 10-09 ( +0.48%) 90% Wed 08-22 ( +1.11%) 94%

Thu 10-10 ( +1.79%) 92% Thu 08-23 ( -0.00%) 94%

Fri 10-11 ( -0.05%) 92% Fri 08-24 ( +1.08%) 95%

------------------------ ------------------------

Mon 10-14 ( -0.49%) 92% Mon 08-27 ( -0.42%) 95%

Tue 10-15 ( -1.06%) 91% Tue 08-28 ( -2.10%) 93%

Wed 10-16 ( -3.20%) 88%

Thu 10-17 ( +1.70%) 89%

Fri 10-18 ( -2.51%) 87%

------------------ -----

Mon 10-21 ( -3.71%) 84%

Tue 10-22 ( +1.75%) 85%

Wed 10-23 ( -6.33%) 80%

Thu 10-24 ( -2.09%) 78% Black Thursday

Fri 10-25 ( +0.58%) 79%

------------------------

Mon 10-28 (-13.47%) 68% Black Monday September 10

Tue 10-29 (-11.73%) 60%

Wed 10-30 (+12.34%) 67%

Thu 10-31 ( +5.82%) 71%

Fri 11-01 (Closed)

-----------------------

Mon 11-04 ( -5.79%) 67%

Tue 11-05 (Closed)

Wed 11-06 ( -9.92%) 60%

Thu 11-07 ( +2.61%) 62%

Fri 11-08 ( -0.70%) 62% September 21

------------------------

Mon 11-11 ( -6.82%) 57%

Tue 11-12 ( -4.83%) 55%

Wed 11-13 ( -5.27%) 52%

Thu 11-14 ( +9.36%) 57%

Fri 11-15 ( +5.27%) 60%

-----------------

Understanding deflation: Why there's less money in the world today than a month ago.:

As the markets continue to fall, the Fed is increasingly in a big bind....

(10-Sep-07)

Alan Greenspan predicts the panic and crash of 2007:

He's said this kind of thing before, but this time it's resonating....

(08-Sep-07)

Bernanke's historic experiment takes center stage:

An assessment of where we are and where we're going....

(27-Aug-07)

How to compute the "real value" of the stock market. :

And some additional speculations about stock market crashes.

(20-Aug-2007)

Ben Bernanke's Great Historic Experiment:

Bernanke doesn't believe that bubbles exist. His Fed policy will now test his core beliefs....

(18-Aug-07)

Redemptions of money market funds now fully in doubt:

Wednesday is the deadline for 3Q redemption of many hedge fund shares....

(15-Aug-07)

Alan Greenspan defends his Fed policies, as people blame him for the subprime crisis:

Greenspan never ceases to amaze, and he did so again on Monday....

(8-Aug-07)

Nouriel Roubini says: "Worry about systemic risk." Whoo hoo!:

His arguments show what's wrong with mainstream macroeconomics....

(6-Aug-07)

Robert Shiller compares stock market to 1929:

He says the recent fall was caused by "market psychology," but is puzzled why....

(20-Mar-07)

A conundrum: How increases in 'risk aversion' lead to higher stock prices:

Maybe because the global financial markets are increasingly "accident-prone."...

(12-Mar-07)

Pundits are suddenly talking about (gasp!) "risk aversion":

Fearing full-scale panic in the mortgage loan marketplace,...

(6-Mar-07)

Alan Greenspan blames the housing bubble on the fall of the Berlin Wall:

Meanwhile, the stock market keeps skyrocketing and appears unstoppable to many investors....

(25-Oct-06)

System Dynamics and the Failure of Macroeconomics Theory :

Mainstream macroeconomic theory, invented by Maynard Keynes in the 1930s, has failed to predict or explain anything that's happened since the bubble started, including the bubble itself. We need a new "Dynamic Macroeconomics" theory.

(25-Oct-2006)

Alan Greenspan gives another harsh doom and gloom speech:

Saying that "the consequences for the U.S. economy of doing nothing could be severe,"...

(4-Dec-05)

Ben S. Bernanke: The man without agony :

Bernanke and Greenspan are as different as night and day, despite what the pundits say.

(29-Oct-2005)

Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan says that the deficit is out of control:

France's Finance Minister Thierry Breton quoted Greenspan...

(25-Sep-05)

Fed Governor Ben Bernanke blames America's sky-high public debt on other nations:

I'm normally wary of applying specific generational archetypes to individuals, but Bernanke is acting like a Baby Boomer....

(14-Mar-05)

Greenspan's testimony further repudiates his earlier stock bubble reasoning:

The Fed Chairman has now completely reversed his previous position on the stock market bubble...

(17-Feb-05)

Alan Greenspan warns that global economic dangers are without historical precedent :

In a speech on Friday, Greenspan buried a major change of position in a speech admitting that his assumptions about the economy for the last decade were wrong.

(6-Feb-2005)

| ||

As you can see, we're sorta-but-not-quite following the 1929 pattern. The fall from the peak isn't as far as it was then in the pattern.

But most important, there haven't been the large downward moves, such as occurred on 10/3/1929, nor has there been the large upward move (+6.32%) that occurred on 10/7. Both of these sharp movements, a downward collapse or an "upward crash," indicate that levels of anxiety and panic are very high. And as we keep saying, the market ups and downs aren't important by themselves; it's the anxiety and panic that are important.

I've estimated that the most likely dates for a panic are in the two weeks, September 10-21. I honestly don't know whether we're still on track for those dates or not. We should have a much better idea by the end of the week.

So here's where we stand: A full-scale panic and crash MUST occur,

because the market is overpriced by a factor of 250%, and it might

occur next week, next month or next year. Based on the enormous

change in attitudes of investors since July 23, it seems very likely

to occur in the next few weeks. And based on speculative comparisons

with 1929, the date range September 10-21 seems the most likely.

(29-Aug-07)

Permanent Link

Receive daily World View columns by e-mail

Donate to Generational Dynamics via PayPal

An assessment of where we are and where we're going.

What was really remarkable about the past week was that "Ben Bernanke's Great Historic Experiment" has been put into full operation.

It's hard to overstate the importance of what's going on. We are now at the focal point of decades of macroeconomic theory that says that the Great Depression need not have happened, and could have been prevented by means of a minor change in Fed policy.

The next few weeks will either prove that Ben Bernanke and the macroeconomic theory that he's implementing are correct or disastrously wrong. Either way, it's truly a historic moment and will be recognized as such for decades to come.

Recall the main points of the experiment, which we'll summarize briefly:

|

The adjoining graphic is a cartoon that's been circulating around the internet showing Bernanke dropping money out of a helicopter. This cartoon alludes to a 2002 speech by Bernanke, where he presumably said that dropping money out of a helicopter would solve any Great Depression by defeating deflation.

Actually, he said something very different in that speech, and I'll come back to that speech in a moment, because it tells us a great deal about where the Fed is going in the next few weeks and months.

But first I want to provide a context by reviewing the extremely remarkable events of the last week.

As we've previously discussed, the Fed reduced the "discount rate" from 6.25% to 5.75% on Friday, August 17. This was done after a week of enormous volatility in the stock market, and signs of greatly increase "risk aversion" among investors and financial managers.

Lowering the discount rate means that banks can borrow money from the Fed's "discount window" at the new lower rate. Thus, the Fed "provides money to the economy" as summarized above.

What has become apparent in the meantime is that nobody wanted to borrow from the discount window, even at the lower rate. There are good reasons for this. Banks rarely use the discount window anyway, because they can borrow money from each other at a lower rate, the "Fed funds rate," which is currently set at 5.25%.

It's true that there were some well-publicized discount window withdrawals by several German banks on Monday.

However, the purpose of Bernanke's great experiment would be thwarted unless it resulted in a lot more money being injected into the economy.

Several hours after the rate cut was announced on Friday (Aug 17) morning, it was becoming clear that the new discount rate was not working as hoped, and on Friday afternoon, the New York Fed (which actually administers the discount window) spoke to the four largest US banks (Citigroup Inc., Bank of America Corp., JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Wachovia Corp.) in a conference call and essentially ordered them to borrow money from the discount window. All four did so, each borrowing the minimum amount possible ($500 million).

The Fed did a few other extraordinary things to encourage use of the discount window:

All of these steps were enough to provide a real shot in the arm to investors, changing their moods from panicky back to giddy, as the Dow went up 1% on Wednesday, and again on Friday.

So now the first week of Bernanke's new policy has come to an end, with results that many pundits are claiming were highly successful. Volatility has come down about halfway to previous "normal" levels, and investor "risk aversion" seems to have been quenched.

I'm being unfair to pundits if I leave it at that, however. A number of pundits have been warning that the worst is yet to come. They point to continuing and increasing problems with mortgage-based securities, as the subprime "teaser rates" continue to be reset in the millions, and they also point out that last week's market was not representative because everyone was on vacation and volume was extremely low. One worried pundit pointed out: "When the market fell, it was on very high volume; when the market recovered, it was on very low volume. This means that investors are really not yet convinced that the Fed moves are working."

(Boomer trivia: The title of this section refers to an early 1960s TV show that ran opposite Twilight Zone.)

In a speech given on November 21, 2002, Bernanke laid out a number of Fed interventions that might take place if the economy became increasingly distressed.

I will now analyze that speech, but I must begin by saying that his reasoning is extraordinarily shallow. He says things that simply don't make sense, and which time has now shown to be completely wrong.

Still, it's a very important speech there's every reason to believe that Bernanke STILL believes almost everything he says there, and because the Fed interventions that he describes are probably going to take place in the next few months. So the speech is important because it provides something of an additional roadmap to the near future.

Let's do this in two phases.

We'll start by making a simple list of the tools that he believes that the Fed can use to inject money into the economy. Then, in the next section, we'll discuss his reasoning.

Here is a list of the tools that the Fed has:

However, it's not an automatic thing. Banks are free to charge each other any interest rate they like. However, if a bank has money to lend, and it can lend the money to another bank at interest rate A, or lend it to the government (the Fed) at interest rate B, then the bank will lend it at whichever rate is higher. That's just common sense. And so, the Fed can control A by controlling B. This is done by "open market operations."

To control B, you have to get banks to lend money to the government, and the way you do that is by selling short-term (overnight) Treasury bills, and let banks bid on them, applying the law of supply and demand. If a lot of bids come in, so demand is very high, then the prices of the bills go up, pushing yields down below 5.25%, so the Fed increases supply and auctions more off; if only a few bids come in, so demand is very low, then the prices of the bills go down, pushing yields above 5.25%, then the fed decreases supply, and stops auctioning. (29-Aug correction)

So the Fed auctions off exactly enough each day to keep the interest rate on the bills it sells at exactly 5.25%, or as close as possible. That's how B is controlled. Once B is set to 5.25%, then A will also return to 5.25%, to compete with the government, and so banks will loan money to each other at that rate.

This is the particular option that Bernanke exercised in the last week, with some variation: it's a 5.75% interest loan (not zero interest), and it's a 30-day loan. It takes as collateral some of the questionable commercial paper that's being backed by subprime mortgage loans, as described previously.

At this point, it's worthwhile to note that Bernanke is pursuing this policy for a different reason than the reason he discussed in 2002. At that time, he was concerned about deflation (as occurred in the early 1930s, and in Japan in the 1990s), and was describing asset-backed loans at zero interest rates for the purpose of combating deflation. This whole idea was based on concepts of deflation that were completely wrong, and have been proven wrong in the intervening time.

Today, Bernanke isn't concerned about defeating DEFLATION; he's concerned about increasing money liquidity in the markets, but without increasing INFLATION. There's an inherent contradiction in such policies, since increasing money liquidity should naturally increase inflation (or decrease deflation, which was his point in 2002). So he's offering discount window loans at 5.75% -- a high interest rate -- to avoid stirring inflation.

Well, if the interest rate is so high, then why lower the discount rate at all? The answer appears to be that it's all psychological. Lowering interest rates to increase liqudity and to defeat deflation makes sense; lowering them to increase liquidity but not to increase inflation really doesn't make sense.

And this is a point that we'll return to: Bernanke's 2002 speech was about avoiding a new Great Depression by controlling deflation. That's not the situation today.

So this is one of many serious problems with Bernanke's strategy.

In fact, the reason that he even lists other tools in his strategy is because he believes they'll be needed when the Discount Rate and Funds Rate go down to zero, and therefore cannot go any lower. (You know, I don't really believe this, but that's a topic for another day.)

I'll now go on and list the remaining tools that he described, because it's of interest to get the whole list down. But remember that they're all geared towards injecting liquidity by controlling deflation.

This is where he made his famous statement:

This is the one part of the speech that everyone seems to remember, but Bernanke wasn't recommending it; he was simply repeating a suggestion by Milton Friedman.

Now that we've listed the main tools described by Bernanke in the speech, let's move on to his assumptions and conclusions.

As I've said many times on this web site, mainstream macroeconomics has been wrong about everything since at least 1995. The mainstream models, which were devised in the 1970s and 1980s, did not predict or explain the dot-com bubble, and could not explain why the bubble occurred in the late 90s instead of the 1980s or 2000s, and could not explain almost anything that's happened since 2000.

It's certainly unequivocally true that no mainstream economist predicted anything that's going on today. This is all a complete shock to mainstream macroeconomics.

Bernanke's 2002 speech illuminates some of the main assumptions that mainstream macroeconomics makes, and it's easy to see from his speech that not only does Bernanke not know what he's talking about, but even HE thinks he doesn't know what he's talking about.

His discussion of deflation shows this quite forcefully, in which he says that deflation is "not a mystery":

Deflation is defined as a general decline in prices, with emphasis on the word "general." At any given time, especially in a low-inflation economy like that of our recent experience, prices of some goods and services will be falling. Price declines in a specific sector may occur because productivity is rising and costs are falling more quickly in that sector than elsewhere or because the demand for the output of that sector is weak relative to the demand for other goods and services. Sector-specific price declines, uncomfortable as they may be for producers in that sector, are generally not a problem for the economy as a whole and do not constitute deflation. Deflation per se occurs only when price declines are so widespread that broad-based indexes of prices, such as the consumer price index, register ongoing declines.

The sources of deflation are not a mystery. Deflation is in almost all cases a side effect of a collapse of aggregate demand--a drop in spending so severe that producers must cut prices on an ongoing basis in order to find buyers. Likewise, the economic effects of a deflationary episode, for the most part, are similar to those of any other sharp decline in aggregate spending--namely, recession, rising unemployment, and financial stress."

Now, you have to laugh at this. It's so ridiculously shallow that you'd think he'd be embarrassed to utter it.

He says that deflation is defined as a general decline in prices. Fine.

What are the causes? It's "a side effect of a collapse of aggregate demand -- a drop in spending so severe that producers must cut prices on an ongoing basis in order to find buyers."

In other words, deflation occurs when producers cut prices, and producers cut prices when demand for the producers' products collapses.

I think I learned that in 10th grade social studies class. Do we really need a Princeton professor of economics to recite it?

What causes the collapse of aggregate demand?? Why do people suddenly stop wanting producers' products? He doesn't answer that. Obviously he no idea whatsoever. He has absolutely no idea why deflation occurs. The above explanation is simply babbling.

In the above, he mentions "recession, rising unemployment, and financial stress" as being related, but he doesn't name them of the CAUSE of deflation. Good thing, too. He's well aware that during the Great Inflation of the 1970s, there was high inflation, recession, rising unemployment, and a great deal of financial stress.

I don't know what I find more astonishing -- the fact that Bernanke says these incredibly vacuous things, or the fact that I'm the only person who points them out. It's like that fairy tale about the King who wore no clothes, and everyone was too embarrassed to say so.

Bernanke and other economists have an extremely simplistic view of inflation and deflation. If you lower interest rates, then more money enters the economy and inflation increases; if you raise interest rates, then less money enters the economy, and inflation decreases or turns into deflation.

From the point of view of Generational Dynamics, the situation is a lot more complicated.

Economists assume that new businesses are born each decade, and die each decade, and each decade is pretty much the same as each other decade. All of their models depend on that assumption.

But that assumption is obviously wrong, as anyone can easily see. Most major businesses today were either born or completely renewed during the Great Depression. They invested heavily in research and development in the 40s and 50s, and reached their zenith in innovation and product excellence by the 60s and 70s. That's why demand was so high for American products, and why high inflation occurred: We just couldn't manufacture products fast enough to satisfy demand.

Since the 1980s, these companies have gotten older. Bureaucracy has increased, and product innovation has taken second place to protecting existing jobs and income streams. The main objective is to protect one's ass. That's why demand for American products has gotten so low, and why prices and inflation are falling.

Even though this is completely obvious, mainstream economists have no concept of it. Their flat view of time, where every decade is like every other decade, is obviously wrong, but it's the underlying assumption of every economic model, and it's why Bernanke is babbling completely nonsense.

Since 2002, the Fed funds rate has been near-zero, and by the standards of their 1970s models, inflation should have been enormous. Instead, inflation remained tame. But Americans rejected American products, and when to China for manufactured goods and to India for services.

Here's what Bernanke said in his speech:

The phrase "use monetary and fiscal policy as needed to support aggregate spending" is what the previously described tools are all about -- inject money into the economy, to increase spending, so that people will buy American products, so that demand will go up, prices will go up, and inflation will go up. Simple huh?

He added the following:

Well, that's what the Fed did in 2002 and 2003 -- moved "premptively and aggressively" to head off deflation, and that's what's brought us to our current state today.

As I said, from the point of view of Generational Dynamics, this is all wrong.

I knew all this in 2002 and 2003, because I had already developed the first two of major measures for valuating the stock market, as described in my recent essay, "How to compute the 'real value' of the stock market." And I wrote about it in my 2003 book, Generational Dynamics, where I referred to the "crusty old bureaucracy" that formed the leadership of most American companies. I knew at that time that we were headed for a new 1930s style Great Depression, but I was wrong about one major thing: I thought that the market would continue to decline from that point on.

In fact, here's what I wrote and posted on January 3, 2003, in my "Stock market forecast for 2003." This was one of my first predictions on this web site, and it contained a number of errors. However, this was also several months before I developed the Generational Dynamics forecasting methodology, and I don't claim to have started getting everything right until then.

Still, it's interesting to see what I wrote on January 3, 2003:

If technological and economic forecasting means anything at all (and it does), then the first of these forecasts doesn't have a chance of happening.

The second forecast may come true, in the sense that the forecasted crash to below 6000 may wait a year or two.

My guess: Something will go wrong in the war against Iraq or the war against terror, something that will expose a new vulnerability. That will have two effects: The DJIA will fall, and public resolve to pursue the war against terror will increase. Even if the war goes well in 2003, the stock market will continue to fall.

My guess is that the DJIA will be in the low 7000s or lower at the end of 2003."

At least I had the good sense to call these "guesses." Since that time, I've learned to say that "Generational Dynamics tells you were you're going, but not the path you'll take to get there," and "a stock market panic and crash might occur next week, next month or next year, but it's coming with 100% certainty, and probably sooner rather than later." In other words, the prediction a stock market crash and a new 1930s style Great Depression was correct, but I was wrong in "guessing" what the DJIA would be.

What I mainly didn't foresee was the "preemptive and aggressive" policy of the Fed, described above, to move against deflation before it got started. As a result, the DJIA did NOT fall -- but not for the reason that Greenspan and Bernanke intended.

The predicted reason that the market would go up is because the low interest rates would create more aggregate demand for American products, thus pushing up prices. That may have happened marginally, but I don't know anyone who could claim that it's happened in any serious way in the intervening five years.

Instead, all that money that poured into the economy was channeled into the huge Ponzi scheme that we're living with today, creating the stock market bubble, the housing bubble and the credit bubble.

The point I want to make here is that Bernanke's speech was completely wrong in explaining what was going on and predicting what was going to happen. Greenspan and Bernanke went ahead with a policy that they didn't understand, and didn't even really claim to understand, but which they thought might work if you have sufficiently simplistic economic beliefs.

If Bernanke's discussion of deflation is shallow, his discussion of Japan is mind-bogglingly bizarre.

I actually wrote a sparse analysis of Japan in March 2003, but wasn't able to complete the picture until February of this year, when I was finally able to obtain historical data on the Tokyo Stock Exchange dating back to 1914, and wrote "Japan's real estate crash may finally end after 16 years."

In brief, Japan had a major generational stock market panic and crash in 1990, just like America in 1929. But Japan's previous major stock market crash was in 1919. So you have: Wall Street: Crash in 1929, new bubble in 1995, 66 years later; Tokyo Stock Exchange: Crash in 1919, new bubble in 1984, 65 years later.

Japan's 1980s real estate and stock market bubble was HUGE. When the market crashed in 1990, prices in Japan fell for 15 years, and only in the last year have begun to rise again.

And yet, Bernanke doesn't believe that deflation is (or should be) possible. He believes that the long deflationary collapse was based on errors by the Bank of Japan (i.e., Japan's "Fed"), and on political confusion. He doesn't EVEN MENTION the 1980s bubble.

You know, Dear Reader, you must think that I enjoy writing insulting remarks about today's political and financial leaders, but really I don't. I hate what's happening, and I hate the utter stupidity of these people in positions of leadership.

But for heaven's sake, this guy was a Professor of Economics at Princeton. How could be possibly be this stupid?

But I digress. Let's quote directly from his speech:

First, here are his reasons for saying that deflation shouldn't occur:

What has this got to do with monetary policy? Like gold, U.S. dollars have value only to the extent that they are strictly limited in supply. But the U.S. government has a technology, called a printing press (or, today, its electronic equivalent), that allows it to produce as many U.S. dollars as it wishes at essentially no cost. By increasing the number of U.S. dollars in circulation, or even by credibly threatening to do so, the U.S. government can also reduce the value of a dollar in terms of goods and services, which is equivalent to raising the prices in dollars of those goods and services. We conclude that, under a paper-money system, a determined government can always generate higher spending and hence positive inflation."

OK, so he tells his little "parable" to say that deflation never occurs as long as you can pump as much money into the economy as you want.

Well, didn't Japan try that, and didn't it fail? Here goes:

The claim that deflation can be ended by sufficiently strong action has no doubt led you to wonder, if that is the case, why has Japan not ended its deflation? The Japanese situation is a complex one that I cannot fully discuss today. I will just make two brief, general points.

First, as you know, Japan's economy faces some significant barriers to growth besides deflation, including massive financial problems in the banking and corporate sectors and a large overhang of government debt. Plausibly, private-sector financial problems have muted the effects of the monetary policies that have been tried in Japan, even as the heavy overhang of government debt has made Japanese policymakers more reluctant to use aggressive fiscal policies. Fortunately, the U.S. economy does not share these problems, at least not to anything like the same degree, suggesting that anti-deflationary monetary and fiscal policies would be more potent here than they have been in Japan."

Well, let's all stop and have a moment of silence. Bernanke in 2002 says that Japan had "massive financial problems in the banking and corporate sectors and a large overhang of government debt." He adds that "the U.S. economy does not share these problems."

Maybe the US economy didn't in November 2002, but it sure does today.

Next:

In short, Japan's deflation problem is real and serious; but, in my view, political constraints, rather than a lack of policy instruments, explain why its deflation has persisted for as long as it has. Thus, I do not view the Japanese experience as evidence against the general conclusion that U.S. policymakers have the tools they need to prevent, and, if necessary, to cure a deflationary recession in the United States."

And so, he doesn't believe in bubbles, even though Japan had a huge bubble in the 1980s. He believes that deflation can be prevented, even though Japan couldn't prevent in the 1990s.

I often talk of the incredible arrogance and narcissim of people in the Baby Boomer generation, and how each one is in the center of the universe, and his words are the Golden Words of Truth, even when they change their minds or ignore any facts.

Here you see arrogance and narcissism at its height. Ben Bernanke, sitting on his grandmother's knee in the 1960s and listening to the "shoe factory" story reached some conclusions about how he was so much smarter than anyone who came before him, and even facts staring him in the face are to be ignored.

How does he explain his views in the face of clear, obvious contradictions in Japan? How does he justify his policies?

Why, it's simple. Japan's deflation was caused by politics. The people at the BOJ and the Japanese Diet were just plain stupid. They didn't know what they were doing, and they argued with each other so much that they never got things done.

And so, like any other Boomer, Bernanke has no concept of what's going on in the world. In the end, he's just like all the other Boomer politicians I talk about on this web site -- he knows how to argue and blame everyone else, be has little ability to actually get things done.

According to a recent article, recently published Fed minutes from 2001 reveal a policy of "calculated ambiguity":

This 2001 policy gives some insight into Ben Bernanke's policy today.

Bernanke has received a fair amount of pundit criticism in the last week, for not going far enough. Pundits have complained that the ½% reduction in the Discount Rate is too small a policy change to have any real effect, and that the Fed should be much more aggressive -- by lowering the Funds Rate ½ point or a full point.

In fact, as we described above, Greenspan followed a "preemptive and aggressive" policy in 2002 to head off deflation.

So we have two conflicting policies here: a "preemptive and aggressive" policy to head off problems before they start, and a "calculated ambiguity" policy that calls for a slower approach so that there's an excuse if the policy doesn't work.

My guess is that Bernanke is following a "calculated ambiguity" policy right now, and will become more aggressive only if it becomes necessary.

But here's the interesting question: As the economic situation becomes increasingly severe, how far will Bernanke go in using the tools described?

Will he go so far as to use all the tools available to him to flood the markets with money, and print so much money that inflation runs away and the dollar essentially becomes worthless?

|

I've been predicting since 2003 that we're in a long-term deflationary trend (like Japan in the 1990s). This is based on the adjoining graph that shows that long-term inflation is running above the exponential growth trend line and so, by the Law of Trend Reversion, must fall below the trend line for a long period of time. This means that the Consumer Price Index (CPI) has to fall 30% or more, which would indicate a great deal of deflation.

However, I've always had in the back of my mind that Greenspan, and now Bernanke, might defeat this trend by making the dollar worthless.

I actually don't believe that will happen. A policy of that type would have to be sustained for several years to have such a deleterious effect, and within a few months it would be seen to be failing.

But up to that point, we can expect to see Bernanke's Great Historic

Experiment proceed with an increasingly aggressive policy of

injecting money into the economy, until it becomes clear that such a

policy is a total failure.

(27-Aug-07)

Permanent Link

Receive daily World View columns by e-mail

Donate to Generational Dynamics via PayPal

Wheat prices hit an all-time record high, as stocks are low, and poor weather has damaged crops in Canada, after Australia suffered a severe drought, and floods have reduced yields throughout Europe.

The latest 30% spike in wheat prices came in response to news that Canada’s crop could be reduced by roughly 20% this year after bad weather hit the world’s second-largest exporter.

Countries that rely on imported wheat, such as Japan and Taiwan, responded with panic buying, pushing the price up.

Demand for wheat is generally up, especially as China and India, as tastes become more westernized, and people demand more pasta and bread in place of traditional rice.

When I last wrote about growing food prices, in an article last month, I noted that some kind of "tipping point" appears to have been reached, and worldwide food prices are really becoming uncontrollable.

Not all agricultural product prices have spiked as much as wheat, but the general trend is to be up sharply. In general, food inflation worldwide is averaging 6-8% over a year ago.

The following graphs show the increase in prices of wheat, corn and rice, respectively, over the last 1-2 years.

(I've mentioned previously that the Wall St. Journal online has been promoting its "historical prices," that go back all of three months in most cases. Well, they must have had a historian in the commodity department, because these figures go waaaaaaaaaaaay back as far as 2005 or 2006.)

|

As you can see from the above graphs, the price of wheat has doubled in two years, corn prices have increased 40-60% in two years, and rice prices have increased about 10% in one year.

Another major source of demand for agricultural demand is the rapidly expanding use if biofuels, led by four regions: US, Brazil, Europe and China. This has increasingly diverted such crops as corn and sugar cane away from food and towards energy production.

According to a a study published in May by Canada's National Farmer's Union (NFU) (PDF), there is a global food crisis emerging.

The following graph illustrates how worldwide stocks of grains have been falling sharply since the year 2000:

|

As you can see, there were 130 days of grain supply stockpiled and available in 1986, 115 days supply in the year 2000, and 47 days supply in 2007.

What's significant is not just the lower level of supply, but the sharp downward trend that shows no sign of abating. What this shows is that increasingly we're eating more food than we produce, and that this trend is continuing and probably increasing.

According to the NFU report,

[T]he converging problems of natural gas and fertilizer constraints, intensifying water shortages, climate change, farmland loss and degradation, population increases, the proliferation of livestock feeding, and an increasing push to divert food supplies into biofuels means that we are in the opening phase of an intensifying food shortage. ...

If we try to do more of the same, if we try to produce, consume, and export more food while using more fertilizer, water, and chemicals, we will only intensify our problems. Instead, we need to rethink our relation to food, farmers, production, processing, and distribution. We need to create a system focused on feeding people and creating health. We need to strengthen the food production systems around the world. Diversity, resilience, and sustainability are key."

You know, this is a VERY serious problem, much more serious than the stylish, designer, fad issue du jour, global warming, and yet everyone's completely oblivious to it.

Food rationing comes to the United States:

After years of price rises, mainstream media is finally recognizing there's a problem....

(24-Apr-08)

Food panics and riots spread around the world:

The unending sharp price wheat, corn and rice prices are destabilizing nations....

(9-Apr-08)

UN World Food Program to institute food rationing:

Surging food prices are causing food riots around the world....

(26-Feb-08)

Wheat price rises blocked by commodities market price increase limits:

American wheat stockpiles are lowest since just after World War II....

(9-Feb-08)

Wheat prices surge above $10 per bushel, sparking little concern:

World food stocks dwindling rapidly, according to the UN....

(23-Dec-07)

UN expert calls biofuels a "crime against humanity":

Separately, Oxfam says that biofuels won't work, and they "trample" poor people....

(7-Nov-07)

United Nations warns of social unrest as food prices continue meteoric climb:

With world wheat prices now up 60% since January, countries are panicking...

(08-Sep-07)

World wheat prices up 30% since May on panic buying:

Wheat prices hit an all-time record high, as stocks are low, and poor weather...

(25-Aug-07)

The global warming fad is becoming the enemy of food production.:

Food prices are continuing to increase sharply around the world....

(16-Jul-07)

Price of food is skyrocketing in India and China:

In fact, crop prices are increasing around the world,...

(11-Apr-07)

In Mexico, violent crime from drug cartels increases with tortilla prices:

After Acapulco incident, Canada may advise citizens not to travel to Mexico....

(8-Feb-07)

UN World Food Program will cut Darfur humanitarian rations in half:

This continuing genocide is a very sad situation, but it can't be stopped....

(29-Apr-06)

In a new bizarre move, North Korea demands an end to U.N. food aid:

The famine-stricken country officially told the UN World Food Program...

(26-Sep-05)

Food prices continue to increase dramatically around the world:

Hunger, poverty and starvation are spreading to increasing masses of people around the world,...

(10-Aug-05)

China appears to be approaching a major civil war :

Unrest is spreading, and economic disparities make China a textbook case for a massive civil war in the making

(16-Jan-2005)

Green Revolution vs Malthus Effect: Despite the "Green Revolution," world population continues to grow faster than food production. This is one of the fundamental reasons why wars occur. (28-Jun-2004) | ||

I get yelled at by web site readers for various things on this web site, but there's no doubt what the number 1 issue is that people get angry at me about: The obvious fact that we're running out of food relative to population, and that soon there won't be enough food in the world to feed everyone.

What I've discovered, listening to people shouting at me on this issue, is that they simply assume that there's enough food for everyone, and that there always will be, and they can't imagine it any other way. It's the same kind of obliviousness that people show toward the increasing instability of the world economy.

I've actually changed my mind about what's going on here. When I've written about this subject in the past, I ascribed the cause of this problem entirely to a statistical fact -- that population grows faster than the food supply grows. But now I see how there's a huge generational factor as well.

After WW II, there was a concerted effort to make sure that everyone would eat, because it was recognized that poverty and starvation were one of the major causes of the war. There was the Green Revolution that brought the latest agricultural technology to countries around the world, especially India. And there have been programs like the U.N. World Food Program that purchases food for needy people.

But the problem is that the population grows faster than the food supply. You can see this from the fact that food prices around the world have been increasing faster than inflation since 2000, and they've really skyrocketed since 2004.

What I believe has happened is that the "Green Revolution" ran out of steam around the mid-1990s, and population growth has been rapidly overtaking food production since then.

But there's another reason as well: The mid-1990s was the time that the dot-com bubble began, and that happened because the people who remember the Great Depression had mostly disappered (retired or died) by that time.

So the "Green Revolution" ran out of steam in the mid-1990s, and the dot-com bubble began in the mid-1990s. Up until now I hadn't related these two events, but lately I've come to believe that they're closely related.

Here are the similarities between the two:

When I wrote in April that "the price of food is skyrocketing in India and China," I quoted the following article from the Wall Street Journal:

This is the epitome of stupidity. The The Wall Street Journal is supposed to be a newspaper of reporters who know what's going on in the world, but more and more they seem among the most oblivious of all.

It has now been eight years that food prices have been increasing faster than inflation, and the rate of growth itself seems to be growing exponentially and uncontrollably.

This may or may not be of concern to most Americans, where only 14% of a family's budget is spent on food, but it's considerably more important in China and India, where it accounts for 33% and 46%, respectively.

I'll take a guess here: Every time that the worldwide cost of food goes up another 1% more than inflation, another few tens of millions of people in the world are thrown into poverty and undernourishment. Tens of millions isn't very much compared to the world population of 6.6 billion, but it is a lot in absolute terms, and it's far more than enough to start a war. When a man can't feed himself and his family, then he has nothing to lose and everything to gain by going to war.

This is particularly true in the huge megacities of the world, each holding 10-20 million people in vertical apartment buildings or shanties, foraging for food in garbage dumps.

The national and world economy is deteriorating so rapidly, that it now seems likely that a major financial crisis will begin in a matter of weeks, based on research on previous generational crises.

I don't have similar research on food crises, but the huge surge in food prices displayed by the graphs at the beginning of this article cannot continue for long, and there is nothing going on in the world that's going to stop it.

We're expecting a major financial crisis, but even a minor one would

be a major disruption to many populations, especially those densely

packed into megacities, where there's no opportunity even to grow a

little food in the backyard.

(25-Aug-07)

Permanent Link

Receive daily World View columns by e-mail

Donate to Generational Dynamics via PayPal

The same people who have been comparing Iraq to Vietnam for years are now babbling incoherently, because of President Bush's comparing the Vietnam and Iraq wars.

Thanks to the economic news, it's been a long time since I've commented on the clown circus in Washington, and this story provides an interesting opportunity.

The lead headline, in big, bold letters at the top-right of Page One of Thursday's Boston Globe was: "President compares Vietnam, Iraq wars".

Wow! That must have been some speech to make it far and away the most important news story in the world! Where's Paris Hilton when you need her?

As usual, almost everything said by both sides was completely wrong, since the Vietnam and Iraq wars have nothing in common except that they're both wars, but it's been a while since I've commented on the clown circus in Washington, so this is an opportunity.

I had expected Bush's speech to be purely political, but when I read the full text of the speech I found it to be VERY interesting because it presents a very good historical summary of the neo-conservative position. I'll get back to it later, but here are the paragraphs that seems to be drawing the most babbling from so-called antiwar Democrats:

The world would learn just how costly these misimpressions would be. In Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge began a murderous rule in which hundreds of thousands of Cambodians died by starvation and torture and execution. In Vietnam, former allies of the United States and government workers and intellectuals and businessmen were sent off to prison camps, where tens of thousands perished. Hundreds of thousands more fled the country on rickety boats, many of them going to their graves in the South China Sea.

Three decades later, there is a legitimate debate about how we got into the Vietnam War and how we left. ... Whatever your position is on that debate, one unmistakable legacy of Vietnam is that the price of America's withdrawal was paid by millions of innocent citizens whose agonies would add to our vocabulary new terms like "boat people," "re-education camps," and "killing fields."

Brookings Institution does a full reversal on Iraq war:

As Americans withdraw from cities, Brookings admits there's no civil war....

(1-Jul-2009)

Stock markets in Iraq and Iran are surging.:

Iran's President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad says "it is the end of capitalism."...

(17-Oct-2008)

On "60 Minutes," Bob Woodward makes ridiculous claims about Iraq.:

He says the surge succeeded because of some magic new military technique....

(7-Sep-2008)

Iraq's Shiite cleric Moqtada al-Sadr turns from arms to "culture":

This follows several Sunni "Tribal Awakenings" to expel al-Qaeda....

(10-Aug-2008)

Obama continues to damage his candidacy with his Iraq policy.:

Obama is hurting himself by bobbing and weaving on the success of the "surge."...

(27-Jul-2008)

The new Iraqi "civil war" fizzles out, as expected:

Radical Shia cleric Moqtada al-Sadr called for a cease-fire on Sunday,...

(1-Apr-08)

The Iraq war may be related to the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.:

On the first anniversary of the successful "surge" strategy,...

(17-Feb-08)

Casualties are down sharply in Iraq.:

This issue has been a spectacular validation of Generational Dynamics theory....

(31-Oct-07)

As Turkey prepares to invade northern Iraq, it's isolating itself internationally:

A new "Young Turks revolution" is reestablishing strong Turkish nationalism....

(29-Oct-07)

Washington Post says that al-Qaeda in Iraq is "crippled":

Meanwhile, Iraqi citizens' political opposition to America is growing....

(16-Oct-07)

Antiwar Democrats are freaking out over Bush's Vietnam - Iraq war comparison.:

The same people who have been comparing Iraq to Vietnam for years...

(24-Aug-07)

Iraq: Suicide bombers interrupt celebrations in Baghdad over soccer win:

Iraq's stunning 4-3 soccer victory over South Korea in the Asia Cup semi-final...

(26-Jul-07)

The al-Askariya Shrine in Samarra, Iraq, is bombed again:

Last year's bombing triggered months of vicious sectarian violence in Baghdad,...

(14-Jun-07)

Congress votes to fund Iraq war without deadlines:

The result shows conflicting anxieties during America's Crisis era....

(24-May-07)

Senator Joe Biden wants to move troops from Iraq to Darfur civil war:

Saying on Meet the Press that we should remove troops from Iraqi "civil war,"...

(29-Apr-07)

NY Times columnist Thomas Friedman shows ignorance and evasiveness about al-Qaeda in Iraq:

In an interview that appeared on CNN on Sunday,...

(24-Apr-07)

BBC kills an Iraqi war story because it's "too positive":

But a drama showing British troops brutalizing civilians is perfectly fine....

(11-Apr-07)

Tens of thousands of Shi'ites protest against American "occupiers":

In what appeared to be a grand, party-like atmosphere,...

(10-Apr-07)

Iraq's Moqtada al-Sadr tells followers to attack Americans, not each other:

This could be good news....

(9-Apr-07)

Iraqi Sunnis are turning against al-Qaeda in Iraq :

This is exactly the kind of thing that generational theory predicts.

(1-Apr-2007)

New optimistic poll of Iraqi people barely mentioned on Sunday TV news shows:

And Bob Shieffer on CBS's "Face the Nation" asked really dumb questions of Secretary of Defense Robert Gates....

(19-Mar-07)

Robert Gates on "civil war" in Iraq.:

Following the release of the Iraq National Intelligence Estimate on Friday,...

(2-Feb-07)

News as theatre: NBC announces it will call Iraq war a "civil war":

On Monday morning on the "Today Show,"...

(29-Nov-06)

President Bush's reference to Vietnam War "Tet Offensive" has journalists in a tizzy:

Airhead journalists have completely missed the point, and the real danger....

(20-Oct-06)

Learning-disabled journalists and politicians continue to predict Iraq civil war:

Occasionally journalists take a break from their heavy-breathing over Congressional pages,...

(8-Oct-06)

General John Abizaid says there'll be no troop cutbacks in Iraq:

This is hardly a surprise to me, though not for the reasons most people give....

(19-Sep-06)

Debate over civil war in Iraq rages over semantics:

An actual crisis civil war in Iraq is impossible, but it's now embroiled in the November elections,...

(23-Aug-06)

Washington becomes hysterical again over an Iraqi 'civil war' :

A civil war in Iraq is impossible, as I've said many times, because only one generation has passed since the Iran/Iraq war of the 1980s. Here's some additional historical information.

(7-Aug-2006)

Israel's war against Hizbollah and Lebanon forces Muslims to choose sides : The war is part of a larger Shi'ite-Sunni struggle, and a stopgap ceasefire will create a worsening environment leading to a much more chaotic situation within a few months (25-Jul-2006) Speculations about a stock market panic and crash : Will there be a stock market panic next week, next month, or next year, and will it lead to a crash? We speculate on some possibilities. (31-May-2006) Journalists have a 'civil war in Iraq' orgy over the weekend:

It's hard to remember when news shows had so much sheer non-stop nonsense...

(21-Mar-06)

I just heard on CNN International: "The threat of civil war in Iraq is over.":

Surprise! Surprise! The press corps was 100% wrong, and I was right....

(28-Feb-06)

Fear of Iraqi civil war nears hysteria:

But there is NO CHANCE WHATSOEVER of a civil war....

(24-Feb-06)

Bombing of 1200 year old Shi'ite mosque inflames Iraq to the verge of massive civil war rhetoric:

Shi'ites conducted over 90 revenge attacks on Sunni shrines on Wednesday,...

(23-Feb-06)

Vitriolic Iraq war politics erupts in Washington:

But the basics of the Iraq war haven't changed a bit....

(21-Nov-05)

After President Bush's speech: What next for Iraq?:

With growing insurgency violence and flagging public support, what's America's "end strategy" in Iraq?...

(1-Jul-05)

Iraqi Sunni and Shi'ite clerics call for restraint:

Analysts, pundits and journalists are still predicting civil war, and they're still getting it wrong....

(23-May-05)

The chaotic Iraq election is only two days away:

The election is on Sunday, January 30, and no one has a clue what's going to happen....

(28-Jan-05)

Brent Scowcroft predicts an "incipient civil war" for Iraq:

Pundits are returning to wishful thinking as the January 30 election approaches...

(09-Jan-05)

Can we withdraw from Iraq in 2005?:

Suddenly the Washington buzz is that whoever wins - Bush or Kerry - will begin to withdraw American troops from Iraq. We look at two historical examples to predict scenarios.

(16-Oct-2004)

Fallujans are getting angry with insurgents:

Just a few hours after my posting that al-Zarqawi's most formidable enemy may be the 40-50 year old mothers of Fallujah,...

(13-Oct-04)

Al-Sadr's Shi'ite militia fighters turn in their weapons:

The war in Iraq took a significant turn this week when the Shi'ite militias agreed to disarm,...

(13-Oct-04)

The press is talking about another "uprising" in Iraq. Yawn.:

Nothing shows more how clueless the press is about what's going on in Iraq than this constant talk about civil war and uprisings....

(7-Aug-04)

Iraq Today vs 1960s America (Revised):

They have much in common: Bombings, assassinations, student demonstrations, violent riots, calls for insurrection and civil war and harsh rhetoric. That's much more than a coincidence.

(8-May-2004)

What Iraqi Civil War?: Early in 2003, I predicted that there would be no popular uprising against the Americans, and that there would be no civil war. After the overthrow of Saddam, I said that an Iraqi civil war was impossible. Despite the constant near-hysteria of the politicians, journalists and high-priced analysts, I've been right so far. Here's why. (09-Apr-04) Anti-Shi'ite Terror Attacks in Iraq, Pakistan: So far, Sunni and Shi'ite leaders in Iraq aren't taking the bait. (2-Mar-04) Terrorist suicide bombings in Iraq may backfire against terrorists: During an awakening period, terrorist acts cause masses of people to shrink from more violence. (19-Aug-03) | ||

Now all of this is perfectly correct. In fact, at the time of the genocidal massacre in Cambodia, leftists like Jane Fonda and William Kunstler were cheering the massacre on because the massacre was being perpetrated by their beloved Communists. "I would never criticize anything that a Socialist government did," said Kunstler. And earlier, Fonda had visited Hanoi and sided with the Communists against America.

So President Bush is shoving all this back in their faces, as well he should. These people have been anti-American jackasses most of their lives, and still are today.

However, it isn't true that Bush has "rejected the comparison" for years, as the Globe article claimed.

Last October, President Bush compared what al-Qaeda in Iraq was doing to the Tet offensive in the Vietnam War. That comparison caused a press tizzy similar to the one going on right now, but see that article for a Generational Dynamics analysis of why that comparison fails.

Furthermore, the antiwar Democrats have been comparing the Iraq war to the Vietnam war all along.

For example, Senator Ted Kennedy compared the Iraq war to Vietnam War in a January speech demanding total withdrawal. Kennedy said the following:

'It became clear that if we were prepared to stay the course, we could help lay the cornerstone for a diverse and independent region.

If we faltered, the forces of chaos would smell victory, and decades of strife and aggression would stretch endlessly before us. The choice was clear. We would stay the course, and we shall stay the course.'

That's not President Bush speaking; it's Lyndon Johnson speaking, 40 years ago, ordering 100,000 more American soldiers to Vietnam."

This is an interesting comparison. What Kennedy didn't mention is the point that Bush just made: After America withdrew, there was a huge genocidal war engulfing the entire region, with millions of people killed in Vietnam, and then in the "killing fields" of Cambodia.

So the question arises: Will a similar genocide occur if America withdraws from Iraq? I've answered this question many times, and won't repeat the whole thing here; there's a good summary in the article on Ted Kennedy's speech from which I just quoted.

There are some importants to remember with the Iraq war versus Vietnam war:

When you look at the long history of Vietnam from the point of view of Generational Dynamics, it's easy to see how the 1960s-70s war had to do with events that were launched centuries ago.

North and South Vietnam have had different ethnic origins, with North Vietnam (Vietnamese Kingdom) originally populated by ethnic Chinese, and South Vietnam (Champa Kingdom) populated by Polynesian settlers from Indonesia and Malaysia. These ethnic differences have resulted in one crisis war after another over the centuries.

The major one occurred in 1471, when the (North) Vietnamese invaded Champa (in the South), captured its capital of Vijaya and massacred thousands of its people, effectively ending the existence of Champa kingdom. The next crisis war, in 1545, partitioned Vietnam into North and South again, until the Tay-son rebellion of 1771-1790, resulting in a united Vietnam for the first time in 200 years.

During the Awakening era in the early 1800s, cultural development blossomed, making it the high point of literary culture in Vietnamese history. Thanks to the French, Christianity bloomed, with hundreds of thousands of Catholic conversions from Confucianism and Buddhism. However, as the unraveling era arrived (1850s-70s), Ember Tu-Duc relentlessly suppressed Christianity, sanctioning thousands of executions.

This led to the French conquest of Indochina, in a crisis war from 1865-1885.

In the Awakening era that followed, 1904 saw the formation of the Duy Tan Hoi revolutionary (anti-colonial) society. 1908 - student uprising in Hanoi. 1925 Ho Chi Minh forms the Revolutionary Youth League. (In 1920, Ho had been in France, where he took part in the founding of the French Communist Party.) During WW II, Ho formed the Viet Minh political / relief organization, for people starving to death thanks to confiscation of goods by the occupying Japanese.

Thus, what we call the Vietnam War was simply the next step, lasting from 1954-1974. First, human wave assaults defeated a French encampment at Dien Bien Phu caused French to withdraw. America sent advisors to Saigon to help the South Vietnamese. The Americans supported the South Vietnamese through the North-South civil war that finally ended with the North's victory in 1974.

The point is that almost any comparison that can be made is irrelevant unless it recognizes those long-established ethnic fault lines and previous crisis wars between North and South.

So, with that background, let's take a look at excerpts from the text of President Bush's speech. It's a very interesting summary of the neo-conservative position, and once you apply generational theory to it, you see why it's completely wrong.

If this story sounds familiar, it is -- except for one thing. The enemy I have just described is not al Qaeda, and the attack is not 9/11, and the empire is not the radical caliphate envisioned by Osama bin Laden. Instead, what I've described is the war machine of Imperial Japan in the 1940s, its surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, and its attempt to impose its empire throughout East Asia.

This is a very interesting comparison, because it compares two times when America was in a generational Crisis era (WW II and today), and two enemies who were also in a Crisis eras: the Japanese then, and al-Qaeda today.

It's not surprising that the Japanese at that time and al-Qaeda today act similarly, since that's how people in Crisis eras act, especially young people when they hate a certain enemy.

The lesson from Asia's development is that the heart's desire for liberty will not be denied. Once people even get a small taste of liberty, they're not going to rest until they're free. Today's dynamic and hopeful Asia -- a region that brings us countless benefits -- would not have been possible without America's presence and perseverance.

The view of Bush and the neocons has been that by fighting in Iraq, the country will be tranformed into a free democracy, as happened in Japan, South Korea and other Asian countries. (They would also point to Germany and Italy for the same purpose.)

I've briefly reviewed the history of Vietnam in this article, but I don't have time today to do the same for all the other countries mentioned. Each country has its own fault lines, its own hatreds, and its own blossomings. When you try to create historical analogies between different countries, it's almost impossible unless you know what you're doing.

What ties all these countries and all other countries together is generational timelines. Each country has a genocidal crisis war every 70-90 years, and Awakening eras halfway between the crisis wars.

This happens whether or not the country's government is a democracy, a monarchy, a dictatorship, or some other form of government.

However, there's another important point: Dictatorships and controlled

economies don't work for long. It's easy to prove, using the

mathematics of Computation and Complexity Theory, that controlled,

regulated economies only work for relatively small populations. As

the population grows, the number of "regulators" grows exponentially

faster than the population, and so either the government regulates

less or it collapses. That's why the countries of North Korea, Cuba,

East Germany and Russia were all stuck in the 1950s for decades under

communism. Capitalism and freedom are not so much ideologies as

mathematical imperatives.

(24-Aug-07)

Permanent Link

Receive daily World View columns by e-mail

Donate to Generational Dynamics via PayPal

Investors seem to have regained their old giggly confidence on Wednesday, as they pushed the market up by a little over 1% (Dow).

With respect to the countdown to September 10-21 that we've been discussing as the likely date range for a major panic, the 1% rally makes no difference at all. What is important is whether investors are getting confident enough to push the bubble up again.

Understanding deflation: Why there's less money in the world today than a month ago.:

As the markets continue to fall, the Fed is increasingly in a big bind....

(10-Sep-07)

Alan Greenspan predicts the panic and crash of 2007:

He's said this kind of thing before, but this time it's resonating....

(08-Sep-07)

Bernanke's historic experiment takes center stage:

An assessment of where we are and where we're going....

(27-Aug-07)

How to compute the "real value" of the stock market. :

And some additional speculations about stock market crashes.

(20-Aug-2007)

Ben Bernanke's Great Historic Experiment:

Bernanke doesn't believe that bubbles exist. His Fed policy will now test his core beliefs....

(18-Aug-07)

Redemptions of money market funds now fully in doubt:

Wednesday is the deadline for 3Q redemption of many hedge fund shares....

(15-Aug-07)

Alan Greenspan defends his Fed policies, as people blame him for the subprime crisis:

Greenspan never ceases to amaze, and he did so again on Monday....

(8-Aug-07)

Nouriel Roubini says: "Worry about systemic risk." Whoo hoo!:

His arguments show what's wrong with mainstream macroeconomics....

(6-Aug-07)

Robert Shiller compares stock market to 1929:

He says the recent fall was caused by "market psychology," but is puzzled why....

(20-Mar-07)

A conundrum: How increases in 'risk aversion' lead to higher stock prices:

Maybe because the global financial markets are increasingly "accident-prone."...

(12-Mar-07)

Pundits are suddenly talking about (gasp!) "risk aversion":

Fearing full-scale panic in the mortgage loan marketplace,...

(6-Mar-07)

Alan Greenspan blames the housing bubble on the fall of the Berlin Wall:

Meanwhile, the stock market keeps skyrocketing and appears unstoppable to many investors....

(25-Oct-06)

System Dynamics and the Failure of Macroeconomics Theory :

Mainstream macroeconomic theory, invented by Maynard Keynes in the 1930s, has failed to predict or explain anything that's happened since the bubble started, including the bubble itself. We need a new "Dynamic Macroeconomics" theory.

(25-Oct-2006)

Alan Greenspan gives another harsh doom and gloom speech:

Saying that "the consequences for the U.S. economy of doing nothing could be severe,"...

(4-Dec-05)

Ben S. Bernanke: The man without agony :

Bernanke and Greenspan are as different as night and day, despite what the pundits say.

(29-Oct-2005)

Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan says that the deficit is out of control:

France's Finance Minister Thierry Breton quoted Greenspan...

(25-Sep-05)

Fed Governor Ben Bernanke blames America's sky-high public debt on other nations:

I'm normally wary of applying specific generational archetypes to individuals, but Bernanke is acting like a Baby Boomer....

(14-Mar-05)

Greenspan's testimony further repudiates his earlier stock bubble reasoning:

The Fed Chairman has now completely reversed his previous position on the stock market bubble...

(17-Feb-05)

Alan Greenspan warns that global economic dangers are without historical precedent :

In a speech on Friday, Greenspan buried a major change of position in a speech admitting that his assumptions about the economy for the last decade were wrong.

(6-Feb-2005)

| ||

On Wednesday, four major U.S. banks announced that they've taken advantage of the Fed's new bargain discount rate, and have borrowed $500 million each. One pundit on CNBC said that this marks the end of the credit crunch, since all this money is now available to lend to people. Happy days are here again. The reporters were all giddy again.