Pussy Riot and Russia's surreal 'justice'

Moscow (CNN) -- There is no basic human right to barge into a church to make a political statement, jump around near the altar, and shout obscenities. But there is most certainly the right not to lose your liberty for doing so, even if the act is offensive.

But that is exactly what happened Friday. A court in Moscow sentenced the three members of the feminist punk band Pussy Riot to two years in prison.

In my two decades monitoring human rights in Russia I've never seen anything like the Pussy Riot case -- the media attention, the outpouring of public support, the celebrity statements for the detained and criminally charged punk band members.

The image of three young women facing down an inexorable system of unfair justice and an oppressive state has crystallized for many in the West what is wrong with human rights in Russia. To be sure, it is deeply troubling.

For me, even more shocking were the images of Stanislav Markelov, a human rights lawyer, lying on the sidewalk with the back of his head blown off in 2009, or the body of tax lawyer Sergei Magnitsky, who died in prison in 2009 after he blew the whistle on a massive government extortion scheme.

The Pussy Riot case shines a much needed, if highly disturbing, spotlight on the issue of freedom of expression in post-Soviet Russia

On February 21, four members of the group performed what they call a "punk prayer" in Moscow's Russian Orthodox Christ the Savior Cathedral. They danced around and shouted some words to their song, "Virgin Mary, Get Putin Out." The stunt lasted less than a minute before the women were forcibly removed.

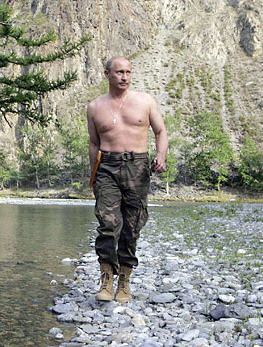

The same day, a video widely shared on social media showed a montage of the stunt with the song spliced in. The song criticizes the Russian Orthodox Church's alleged close relationship with the Kremlin and the personally close relationship of President Vladimir V. Putin with the patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Three of the band members were tried on criminal "hooliganism" charges. Their trial was theater of the absurd. In their closing statements, the women and their lawyers delivered devastating critiques of the state of justice and civic freedoms in Russia.

During the Soviet era, the human rights landscape in Russia was stark. But since then the situation has been harder to figure out, often making it easier for outsiders simply to give the government a pass. But the devil is in the details.

It has been incredibly difficult to pin down any involvement of officials in the beatings and murders of investigative journalists and human rights activists. And the government, while not silencing civil society groups outright, tries to marginalize, discredit, and humiliate them, and crush them with heavy-handed bureaucracy, trumped-up accusations, threats and the like.

Whatever misdemeanor the three women incurred for their antics in the church should not have been transformed by the authorities into a criminal offense that in effect punishes them for their speech. It's typical, though, of how the authorities try to keep a lid on controversial issues. The Russian think tank SOVA has documented dozens of cases in recent years in which the authorities used the threat of extremism charges to silence critics.

This also isn't the first time Russian authorities have misused criminal legislation to stifle critical artistic expression. In 2010 a Moscow district court found the co-organizers of a controversial art exhibit guilty of the vague charge of "inciting religious hatred." The art exhibit organizers were fined.

By making the Pussy Riot band members await trial in jail for almost six months, the authorities made clear how they plan to set boundaries for political criticism.

After a winter of unprecedented, peaceful opposition protests, a dozen demonstrators whom the authorities claim were involved in a scuffle with police during a mass demonstration in May have been arrested and are being charged with crimes grossly disproportionate to their alleged actions. Police have searched opposition leaders' homes.

Laws rammed through Russia's parliament this summer sent more signals: criminal liability for leaders of nongovernmental organizations for "serious breaches" of new restrictive regulations; much tougher sanctions for violating rules on public assembly; and new restrictions on the Internet that could easily shut down big social networking sites. Critics of the Kremlin have been subject to vicious harassment, intimidation and grotesque public smear campaigns.

For years Russian human rights defenders have tried to draw attention to the lack of independence of the courts. With the unprecedented attention to the Pussy Riot trial, the surreal state of justice when political interests are at stake is there for all to see. What we really should be wondering isn't why Pussy Riot is so distinctive, but whether it's just the tip of the iceberg.

Too often, foreign governments have resorted to wishful thinking about the direction Russia is heading. Talking about human rights at a high level -- where all things in Russia are decided -- is unpleasant business. It might be hard, but Russia won't respect other governments if they shy away.

If three women in the defendants' cage had the courage to speak out about where Russia is headed, surely members of the international community should too. They, at least, won't be thrown in jail.